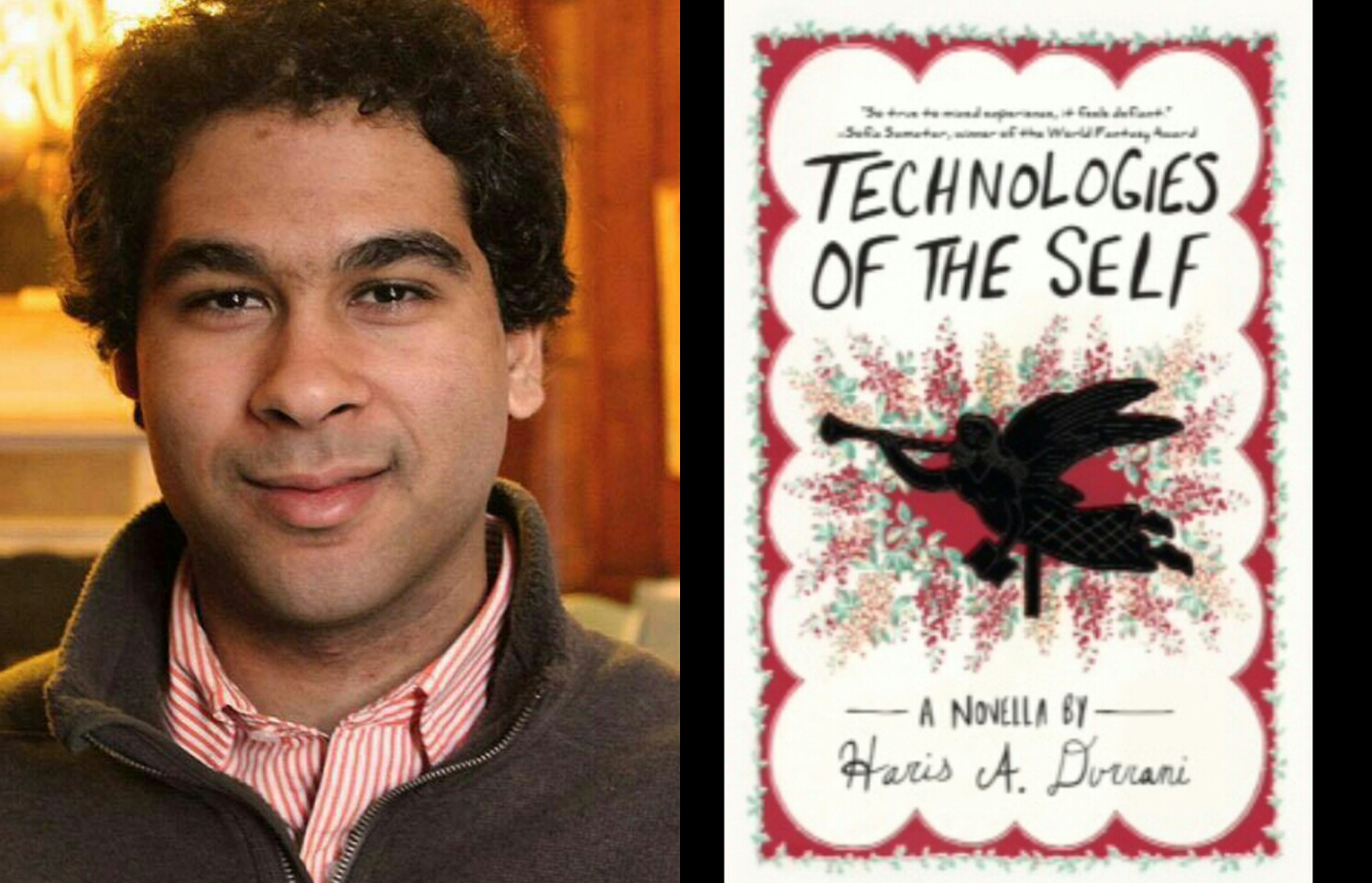

Haris A. Durrani is an M.Phil. candidate in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. He holds a B.S. in Applied Physics from Columbia University, where he minored in Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies and co-founded the Muslim Protagonist Symposium. He is the winner of the McSweeney’s Student Short Story Contest. He is an alum of the Alpha Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror Workshop for Young Writers and was a 2011 Portfolio Gold Medalist in the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, for which he currently serves on the Alumni Council.

Saadia Faruqi is Pakistani American author of “Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan” She writes for a number of publications including Huffington Post and The Islamic Monthly about the global contemporary Muslim experience and about interfaith dialogue. She has trained law enforcement on cultural sensitivity issues and offers community college classes on a variety of topics related to Islam and Muslims. She is editor-in-chief of Blue Minaret, a magazine for Muslim art, poetry and prose.

Saadia Faruqi: You are several hyphenated identities. What has it been like growing up in a post 9/11 world and does that hyphenated identity have something to do with your writing?

Haris Durrani: It’s hard for me to answer this question succinctly and clearly. Yes, my mother is from the Dominican Republic and my father from Pakistan, and I grew up in a post-9/11 world, but I can’t express what all of that means in only a few sentences here. Technologies of the Self is an attempt to capture these experiences. The text itself is probably as close to an answer as I can offer you. But I can talk about how I approached these experiences when writing the book. The protagonist, Jihad, of Technologies of the Self contains all of these identities, and my other works often feature mixed characters. But I never make “hyphenated identities” explicit in the text – I will rarely say a character is “a Muslim Dominican Pakistani American.” This is because, first, I want to show and not tell. Identity isn’t just about a name. It’s about the experience it evokes. Being Dominican is not just about saying, “I’m Dominican.” It’s about the feeling of salty plátanos verdes on your fingers, the memories that the smell of sancocho evokes, the history and family you are a part of, and the way people see and treat you in the world.

Secondly, I wanted to dislocate my readers. By the necessity of marketing, the blurb of my book, and probably every review, will tell readers my hyphenated identities or Jihad’s. But I think the best reading of the story would be with a blank slate. You enter expecting the status quo: a white protagonist. But quickly you realize he’s Dominican. But then you learn his father is from Pakistan. And that he keeps halal. But his Dominican family is Catholic. Except for his Evangelical aunt. And his mother apparently converted to Islam. It can seem very confusing… I want to confuse my readers in order to push back against their assumptions. When I workshopped early drafts of the story with my peers, who didn’t know my background, it took some of them into the second chapter or so to put everything together. Even the protagonist does not reveal that his name is Jihad until halfway through the book. We connect to stories because we can relate them to things we know – social norms, stereotypes – and I find it incredibly powerful, and amusing, to turn these expectations around. Technologies is an exploration of contradictions.

These are very normal stories to me, stories of the people I know, but they are not the kind of stories I’ve ever read on a page or seen on a screen, because the general public is inundated by simplifications. There’s the Bush era rhetoric – what Bush said in his speech right after 9/11 – where he emphasized that not all Muslims are “bad Muslims,” only those against American interests, setting the groundwork for (although certainly not inventing) binaries like good Muslim/bad Muslim and American/anti-American. Then there are the novels and plays about Muslims – sometimes written by Muslims or writers from Muslim backgrounds – who are either stuck in the backwardness, claustrophobia, militancy, and literalism of Islam, or are liberated by a secular, maybe “spiritual,” outlook. The problem with all of this is that Islam is taken as a form of polemic, an ideology, a name, rather than something that is integral to how Muslims experience the world. Even now, anytime Islamophobia peaks – which seems to be every other week, these days – a slew of articles and videos swarm the Internet, attempting to show that Muslims “aren’t all terrorists” or that they are just as “American” as anyone else. These reactions always leave me a little bit empty. I don’t think discrimination is fought in five-second soundbites on CNN or with viral videos or on the latest HuffPost piece. I would say that Technologies tries to show what “normal Muslims” are like, except that normality here runs against expectations — certainly not the Fox News idea of a Muslim, but not the assimilating “Muslim American” either. During this insane election cycle, we read articles and watch videos about what Muslims or Latinos are like — that they are “normal” — but I don’t think soundbites and clickbait will get us very far. They are as ephemeral as this election cycle, which only reflects deeper anxieties in both conservative and liberal camps.

By contrast, stories and art relate important experiences in lasting ways. A good book will stay with you. If we want a shelf of lasting stories, we need to support each story, one by one. It’s an idea that is antithetical to how we digest the power of social media, where things need to be clear-cut and digestible, but I think people need a fundamental shift in thinking away from the ephemeral and toward a deeper understanding of faith and identity. If Muslims and Latinos really want to combat xenophobia, we need to be in it for the long haul. For me, this means supporting stories and art.

SF: Tell us about your book. What is the main message and premise behind it? Who is your target audience and why should they read it?

HD: I believe that a good story is its own best description. This one in particular is a hard book to describe simply, but I will try! It’s a fictionalization of my uncle’s experiences arriving in Spanish Harlem from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s, where he encounters a time-travelling conquistador demon “space knight” named Santiago, the incarnation of Santiago Matamoros / Matajudíos / Mataindios (Moor-Slayer / Jew-Slayer / Indian-Slayer) from the Spanish Inquisition. It is also a fictionalization of my relationship with my uncle and my mixed Dominican, Pakistani, and Muslim cultures, histories, and mythologies. There are Washington Heights-dwelling demons, robots, other dimensions, Dominican mines, jinn, and sentient video games. The protagonist is named Jihad, but prefers to go by the whitewashed “Joe.”

I also believe stories don’t have messages, although authors always have agendas, whether they admit it or not. Talal Asad’s last two chapters of Genealogies of Religion are a brilliant examination of this. I think and hope my book is a bit of a Trojan horse for liberals (I mean here the liberal, secular-minded), in that I am interested in showing that identity and faith are about experiences, not just polemic or ideology. As I said earlier, I want to confuse people’s expectations – what white, even liberal, America thinks about Islam, Muslims, or immigrants. But also what we think about ourselves. Jihad’s reluctance to call himself by his own name. Santiago as a venerated saint in Latino culture, but also the symbol of the destruction of our heritage. The story can also serve as a counterexample to those skeptical of interfaith. And I hope Muslims and Dominicans alike can identify with the story and its characters and see ourselves at the front of the narrative.

This is a hard story to pitch. I think at the outset it can appeal to many different kinds of readers: readers who like science fiction/fantasy, who like diasporic authors like Junot Díaz or Adichie, who are interested in “religious fiction,” who are into philosophical questions about science and reality, or who like political philosophy. But, by the end, the story will likely upset anyone’s expectations. I hope it’s eye-opening but also a little bit unsettling. Stories need to destabilize in order to empower.

SF: Your background is engineering/robotics, as different from writing and humanities as night is from day. What was your motivating factor i.e. why did you finally decide to take the plunge into the writing world?

HD: I don’t think engineering is that different from writing. They are both, at their heart, creative processes. So many of the people I look up to, from early Islamic scholars like al-Biruni and Ibn Sina to the modern polymath Isaac Asimov, worked across disciplines.

I never made a decision to plunge into the writing world. I have always loved writing and reading as much as I loved building robots, and I’ve pursued both. What I write and read inspires what I build and research, which in turn inspires my writing. I think, in particular, that stories allow me to engage the social, political, and moral consequences of engineering. More recently, I’ve decided to pursue law school, with an eye toward law and technology. For me this is the perfect meeting of worlds, where I can put my deliberations about technology and disenfranchised communities to practical use.

Writing in particular is important to this interdisciplinarity because it allows me to not only contextualize what I do in engineering or law, but also to access what is inarticulable about these fields. For example, I think so many medieval Muslim scholars wrote poetry and parables alongside their scientific works, legal treatises, or theological texts because art was a way for them to engage “the spirit” of what they were doing, “the spirit of the law.” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote: “The novelist says in words what cannot be said in words…I am an artist too, and therefore a liar. Distrust everything I say. I am telling the truth.” Justice is about experience, about ways of living more than a message or doctrine, and stories are a conduit to experience.

SF: What advice would you offer Muslims who are considering writing as a career path?

HD: A piece of advice I’ve heard given to Muslims or people of color is to not focus on writing about identity, but simply to write a “human” story – write about something in your daily life, something that’s not explicitly about being, say, Latino or Muslim. This advice says that aspiring writers should not feel bound to write about, say, the mosque or about profiling. I want to dispel this appeal to the “human” story, this idea that stories are “universal,” because what we think of as “human” or “universal” is a product of our social experience. I think this kind of advice assumes that identity is only a name, and that it is not something lived, that “who you are” is not inherently present, explicitly or otherwise, in your everyday experience. This assumes that there is a “normal” experience outside of your social and political identities. That “who you are” is distinct from “how you are” or “what you do.” I would encourage Muslims who are considering writing as a career path to write whatever they want, whether it’s about the mosque or about something as simple as pizza, but not to lose sight of identity as a lived experience. Bravely embrace who you are, no matter the subject you are writing about.

1 Comment