When I arrived for Eid-ul-Adha prayers at Noor Cultural Center in Toronto, my hopes were not high. I have been, over the years, to dozens of mosques, in half a dozen countries, on four continents. Sometimes, I’ve been looking for a mosque to call home, a source of intellectual and spiritual community, a place where I would be challenged to be better, reflect more. Sometimes I’ve just been compelled to go, to hear the call to prayer, or to be in an empty hall and make my two rakats in gratitude. I have almost never felt welcome.

I only hoped one thing in coming to prayers at Noor: that my mere presence in the mosque, for once, not be viewed as fitna.

Fitna has several related meanings in both colloquial and Qur’anic Arabic, including temptation, civil strife, disruption, discord, and rebellion. The word is applied frequently in western Muslim communities to women who are considered too vocal and too visible. For example, I have heard the word used to describe Dr. Amina Wadud, for leading a mixed gender congregation, and to describe any woman who opposes the position of women at the back of a prayer hall or behind a barrier. The word surfaced several times at a panel called Empowering Muslim Women in Sacred Spaces that I moderated for the Council on American-Islamic Relations of Pennsylvania in 2016. Fitna, always asserted in Arabic, is used in these contexts to destroy the will of women to ask questions, to make statements, to show up and above all, to make anyone uncomfortable.

I have been accused of creating fitna for most of my life. It started when I was nine and stood next to my father in prayer. My mother hadn’t come with us to the mosque that Sunday, and I was standing between my father and older brother, several rows back from the imam. The prayer had started when a strange man reached into the row to grab me, roughly by the arm. Although the man had disrupted the prayer of everyone in that section of the mosque, no one said a word, except my father who followed and demanded an explanation. My prepubescent presence in the line between father and brother was too disruptive, a temptation to the grown men around me. My father asked me later that day if I’d like to speak to the imam about what had happened.

I thought I did, but realized quickly that the imam had no particular skill or experience in speaking to a child, let alone a female child about such things. He rambled in a heavy Egyptian accent, “when zee man stands behind zee woman, he has certain feelings…” I answered, “but when women stand behind men, don’t they have the same feelings?” The imam flushed a dark red and turned quiet. My father held my hand on the way out to the parking lot. I was only nine, after all. He asked if the imam’s explanation had satisfied my concerns. Without hesitation, I said no. To his great credit, my father replied frankly, “me neither.”

More than thirty years later, at the 2016 Empowering Muslim Women in Sacred Spaces panel, a well-respected scholar provided a review of how juristic opinions had developed after the prophetic command that women not be barred from the mosque. He discussed the almost immediate deviation from the sunnah in the Islamic legal tradition, including an absurd Maliki tradition in which beautiful women ought specifically be forbidden from coming to the mosque at all. He explained that the concept of men and women as fitna for one another had been expanded to an extreme, and the example of the prophet had come to be seen as an exception, not a rule.

Still, he asserted that the division of the sexes during prayer, with men at the front, male youth and slaves behind them and women at the back was immutable based on hadith, and dismissed any concerns about it as a blind adherence to liberal ideals. The scholar went on to assert crassly, much like the imam of my childhood mosque, that women ought not “stick their butts in front of a guy’s face.” Women outnumbered men at that event, and several took issue, one explaining that while the problem of men having women’s rear ends in their faces might seem to be resolved by having women pray in the back, the persistent issue of women praying with a view of men’s rear ends had not. That woman later apologized for taking issue, for creating fitna.

Most recently, I engaged in an online conversation with a young man I know, who is a thirty-something American imam, and a couple of others I do not know. In it, I called into question a post proclaiming the virtue of Pakistan’s first lady, Bushra Maneka, appearing in a pure white niqab and abaya, nails heavily manicured and eyes darkened with make-up. I suggested that the niqab in such a context was not a demonstration of modesty, but of elitism and class privilege. I learned, in that discussion, that the problem of misogyny transcends generations. I learned that there are Muslim men ten years my junior who will argue that women’s faces are sinful. And there is a whole new generation of men inclined to view women who take issue with these assertions as creating fitna.

I am no longer interested in assuring anyone that I am benign, or that I am good, or that I am apologetic enough for my voice or my body to have a place at the table or in the mosque. I have come to understand that it is the sound of my voice, no matter what I am saying, that so many Muslims find fitna. In countless, devolving conversations about how much of my body (specifically) and a woman’s body (in general) should be covered, how much of a woman’s face and hands, how loosely, with which color of fabric, in which circumstances, I have learned that it is the fact of my body, no matter how I am dressed, that so many Muslims find fitna.

And so it was with overwhelming joy that I experienced the prayer and the place of Noor Cultural Center on Eid. It was the first time I had been in an open congregation where men and women prayed divided right and left, with an aisle, but no barrier in between. Several of us parents of young children took full advantage of being able to stand across from each other, able to pass a fussy baby or a child who needed a break from the khutbah, or sermon, back and forth.

The physical space of Noor is simple and beautiful. But the most notable characteristic of this space and this prayer was the presence of mutual respect, and, as a consequence, the complete lack of ogling. No one was checking to see who stood on which side, so that the man who needed to swoop up his renegade toddler from across the aisle did so easily. No one seemed to care one way or the other that his partner, and the toddler’s other father, prayed beside them. There was less gold and glitz, less ostentation of every kind, whether in a show of wealth or of piety. It was a prayer mindful of this verse in Surah Bakarah,

Righteousness is not that you turn your faces toward the east or the west, but [true] righteousness is [in] one who believes in Allah , the Last Day, the angels, the Book, and the prophets and gives wealth, in spite of love for it, to relatives, orphans, the needy, the traveler, those who ask [for help], and for freeing slaves; [and who] establishes prayer and gives zakah; [those who] fulfill their promise when they promise; and [those who] are patient in poverty and hardship and during battle. Those are the ones who have been true, and it is those who are the righteous.2:177

Women wore every manner of prayer scarf, often opting not to cover until the moment of prayer. Many men wore kufis or other headgear, and many did not. The importance for me is that it did not seem to matter. And when the president of Noor, Samira Khanji, got up to speak, and after her, Dr. Timothy Gianotti led the prayer and gave the khutbah, the reasons for this became evident. Both spoke humbly, focused on the importance of social justice, of the need to strive together in good works. One thing Dr. Gianotti said made me stop to take notes: we must stop weaponizing our ignorance to preserve our comfort. And I realized that what I saw around me was built on this ethic. Each member of that congregation had tacitly agreed to leave whatever bigotry and biases they may have had at the door, to embrace what might, at first, be uncomfortable, to be a part of an accessible, open, vibrant space that welcomed everyone who came to worship.

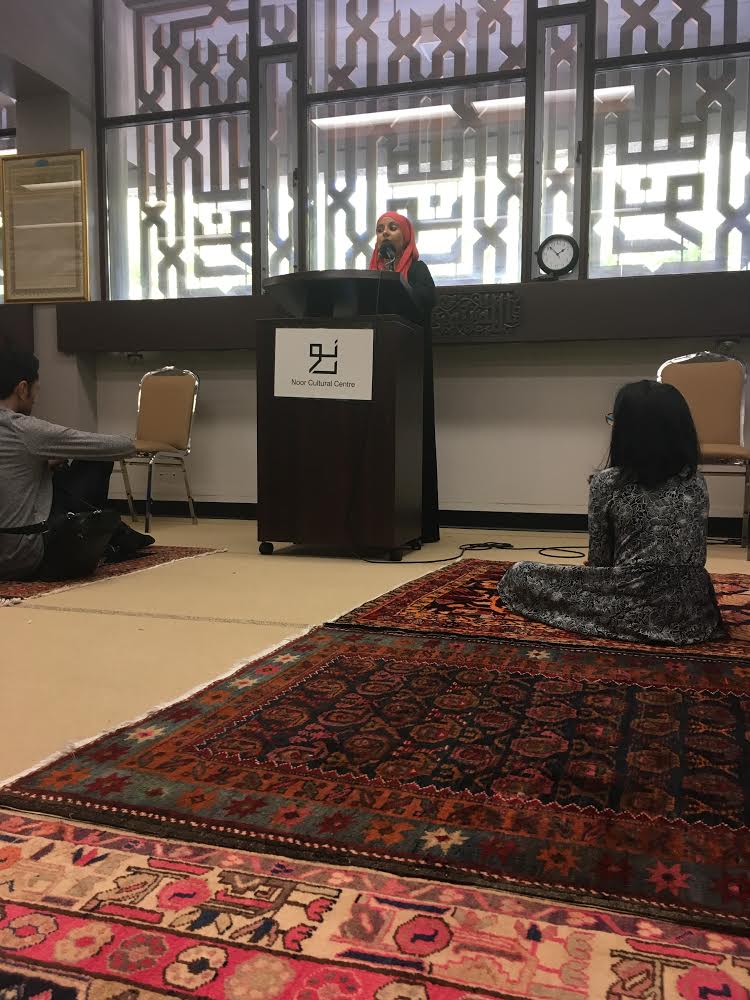

My family and I returned to Noor the following Friday for congregational prayers and a khutbah given by Azeezah Kanji. She spoke eloquently about Muslims’ identification in the Abrahamic lineage with Hagar, a black woman of faith, destined for single motherhood and forced migration, left with only her faith and her son in the parched desert. She spoke of the duty that we have before us in a world where war and political turmoil has forced so many refugees to flee across deserts and oceans around the globe. I have never heard a woman give a sermon from the minbar, let alone a compelling sermon on our obligation to work for justice. Her message and her presence brought a realization, an Eid gift which I have been waiting 44 years to receive:

Women, LGBTQ Muslims, Muslims marginalized because of race or sect, are not fitna, and we are not creating fitna when we take our places in Muslim communities. Our voices, our bodies, our calls for inclusion or justice—none of these are, in and of themselves, fitna. Fitna was not when I asked the imam, at nine, whether women had sexual feelings just as men. Fitna was, instead, created when a man pulled my young body from between my father and brother, interrupting our prayer. Fitna was not in the women who questioned their place at the back of the mosque, or the woman who took issue with the panelist’s crass hypocrisy. Fitna was instead created by the willingness of that scholar (and hundreds of years of scholars before him) to assert the primacy of men’s sexuality in the mosque, while erasing women’s sexuality and minimizing their desire for true inclusion. Fitna was not in my critique of Bushra Maneka’s couture niqaband manicure. Fitna is in the gaze that finds women’s faces sinful.

Sofia Ali-Khan is a Muslim American public interest lawyer and writer. Her recently viral post, “Dear Non-Muslim Allies,” and other writings can be found at sofiaalikhan.com.

It’s sad that Muslim men have such twisted beliefs or behaviors that they are expected to have sexual feelsing when interacting with women at prayers. Try a Christian or Jewish place of worship. People are happy, interact, and no sexual awkwardness at all.

It is important to remember that it is Allah created men and women, and it is Allah who makes certain things right and others wrong. Allah created men and women differently, and if He did not do so, then we would not use different terms to differentiate between the two. Allah also knows the capabilities of both men and women and thus enforces on both of them rules and regulations that are achievable.

So when we start talking about “the woman’s place in the mosque” or “society” or “the household”, etc, we first need to remember that no matter what we or society thinks should be correct, it is Allah whom has already determined what is correct. And even if all of society thinks otherwise, the ruling on this will never change. Because it is us that need to change and obey Allah, not the laws of Allah that need to change to suit our wants.

A women’s place in the mosque is at the back, and the less the two sexes see each other, the better. This is what has been conveyed to us by Allah through the actions and statements and approvals of His Messenger, Prophet Muhammad peace be upon him. So we, as slaves of Allah, should try to change our perspective and obey and follow the way of His Messenger, peace be upon him.