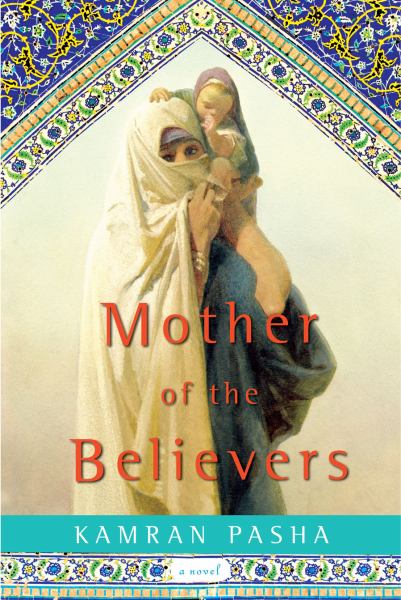

There is much to recommend about Kamran Pasha’s powerfully and sensitively written new novel Mother of the Believers, where Pasha proves his mettle as a writer representing the voice of a fiery and controversial female protagonist who lived fourteen hundred years ago.

Aisha bint Abu Bakr, the youngest wife of Prophet Muhammad, is one of the most controversial and pivotal figures in early Islamic history. Not only did she witness the Prophet actually receiving revelations, she was purportedly the reason why one of the verses in the Quran was revealed. In Surah Al-Noor, God Himself exonerated Aisha from the accusations of adultery that marred her name and created conflict in her marriage. She is remembered by Muslims not only as a scholar, poet, and historian, but also as a warrior and a woman involved in the politics that deeply shaped the Muslim empire, having led an army of a thousand men against Ali ibn Abi Talib in the Battle of Bassorah.

The story of Aisha stands in stark contrast to the Muslim woman as she is conceptualized by the popular media today. We are daily deluged with images and stories of Muslim women who are essentially the voiceless and passive victims of Muslim men, who are flogged in public, killed in the name of “honor,” beheaded in abusive relationships. This is truly a time to look not only for the many real modern Muslim women who do not fit these stereotypes, but also to turn to the very roots of Islamic history and focus on the strong women who were an integral part of the rise of Islam. Given the urgent need for Muslims to define themselves through the lens of the popular media and take back our image, Kamran Pasha’s debut novel Mother of the Believers: A Novel of the Birth of Islam could not be more timely.

Pasha’s novel is a fictionalized account of Aisha’s life, told in the form of Aisha’s memoirs. There is much to recommend about this book. It is written powerfully and with sensitivity, and Pasha proves his mettle as a writer through his ability to represent the voice of a fiery and controversial female protagonist who lived fourteen hundred years ago. Though Aisha is the central character in the book, Pasha spends substantial ink in sketching the characters of many of the other important women of the time, and highlighting through these depictions the bravery, faith, and strength of these strong historic female figures.

Pasha shows Sumaya, the first martyr of Islam who was tortured and killed for refusing to relinquish her faith. He focuses on the central role of Khadija, who is depicted as a majestic woman who was Muhammad’s greatest support and who became the first Muslim. He sketches out the motivations and strength of Umm Ruman, Aisha’s mother, who gave birth to Aisha, the first child born into Islam, at the age of thirty-eight, and who suffered heartache and great sacrifices in her will to follow Muhammad. Aisha’s sister Asma, a central character in the novel, is shown as a resolute young girl who gave up her mother to embrace Islam, as a young woman who risked her life to bring provisions to her father Abu Bakr and Muhammad when they escaped from Mecca and hid in a cave, and as an adult who was Aisha’s greatest support and confidant.

Interestingly, aside from Aisha, one of the stars of this book is Hind bin Utbah, the wife of Abu Sufyan. As Aisha states: “History follows the deeds of men, but often ignores the women who influenced momentous events, for good or for evil.” (229). In Pasha’s finely crafted portrait of Hind, we find every trait that is abhorred by hard-line Muslims today. She is openly seductive and uses her sex-appeal to control and motivate the men of Mecca, engages in adulterous hetero- and homosexual relationships, and is involved in several plots to stamp out Islam and kill the Prophet and his followers. At the Battle of Uhud, she causes the murder of the Prophet’s uncle Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib and in front of the horrified eyes of both armies, mutilates his corpse and cannibalizes him. Despite all her sins, she is ultimately accepted into the folds of Islam and forgiven by Muhammad himself. By focusing on Hind, Pasha highlights the complex nature of the Prophet and Islam itself, and rebuts the one-dimensional portrayal of gender relations that are shown in the media today. It is difficult to reconcile this religion with the actions of the men who flog women for being seen without proper chaperones and others of their ilk who have misappropriated the religion of Muhammad to oppress and dehumanize women.

Pasha’s other great achievement in this book is that he manages to place Islam, its key early events, and even some of its core principals within the context of a great historic story. Rather than choosing a complicated narrative style and moving back and forth between various phases of Aisha’s life, Pasha sets out the tale in a neat chronological order. This format also helps the reader understand the background of many verses of the Quran, and the logic behind some of the Prophet’s decisions in both peace and war. A particularly moving scene is when the Prophet gives his final sermon, and the reader is swept into the vividly described moment, in which Muhammad stands on the mountain of Arafat looking down at the sea of Muslims, delivering his final words. Aisha writes:

As I looked upon the sea of white-garbed pilgrims, all dressed in equal humility regardless of wealth or status, with fair-skinned and dark-skinned believers praying side by side to the same God, I was struck by my husband’s remarkable triumph. He had taken a group of fiercely divided tribes, at war with one another for centuries, and had forged them into a single nation. A community that valued moral character over material success, an Ummah in which the rich eagerly sought to alleviate the suffering of the poor. Such a feat could not have been accomplished by a thousand great leaders over a thousand generations. And yet my love had done it single-handedly over the course of one lifetime. (441)

Because the reader has followed the trials and tribulations of the Muslims and particularly of Muhammad that preceded this historic day, it is difficult not to be awed by this scene and by Muhammad’s accomplishments.

While this, and many other well-crafted scenes in this book make it both informative and entertaining, it could have been even better and less controversial if Pasha had included a bibliography keyed to each chapter at the end of the book. Though it is of course a work of fiction, the story depicted is based on historic events. Given the deep sensitivity of the Muslim community to anything relating to the Prophet and his life, Pasha’s oversight was puzzling. It is possible that Pasha, a trained lawyer, deliberately chose to forgo a bibliography in order to make the point that it is the greater story and not the details that matter.

The extent to which the book focuses on the sexual relationships between various people is both surprising and unnecessary. Even some of the critical developments in early Islam are introduced through their relationship to some sex-related subject. For instance, when the Prophet reveals his night journey to Jerusalem and heaven to his followers, their discussion becomes focused on his revelation that there will be virgins available in heaven. This causes the women to become jealous, and the Prophet then assures them that they will also become virgins when they get to heaven. It seems odd that the discussion is not focused on the more relevant and important aspects of this miraculous event.

Furthermore, throughout the novel there are many sex-related scenes that would seem more appropriate in a romance novel. Many of these scenes involve the Prophet himself, and I found these to be simply offensive. These scenes seemed gratuitous and detracted attention from many of the important religious and historic events developing at the time. While Pasha may have meant to humanize Muhammad through this detailed focus on his relationship with his wives, I found that they instead took attention away from his skills as a leader and statesman.

Pasha’s treatment of the controversy surrounding Aisha’s age at the consummation of her marriage to Muhammad is another disappointment. In the novel, Aisha is nine years old at the time of the consummation. There are many different views on the subject of her actual age, and by choosing the age of nine Pasha clearly wanted to rise to the challenge of explaining within the context of the time and place the reasons for this union. I personally did not find his treatment of the subject particularly adept or on-point, because Pasha’s representation of Aisha’s thoughts seemed so far removed from the probable reality of the situation.

Despite these criticisms, I was gratified to read this book and relearn so much of what I had forgotten about early Islamic history and the struggles of the early Muslims. Pasha brought these people to life, assigned to them colorful and memorable personalities, and laid out in vivid detail the chronology of seminal events in early Islam. Pasha has provided in an entertaining form a clear story of the roots of Islam, the context for its fundamental tenets, and the real rights of women in Islam. It is a great accomplishment for a first time novelist and a must-read for both Muslims and those seeking to learn the basics of both the history and fundamentals of Islam.

(Photo Source: Book Depot)

Uzma Mariam Ahmed is a Contributing Writer to Altmuslimah