In the years since 9/11, Muslim men and women have responded to nativist hate mongering by working within the American legal framework. Muslim women have made the hijab a civil rights issue; similarly, the fight for the human rights of detainees has been going strong for some time. An additional response – one that is more nuanced to the gendered aspects of the problem – is to use gender and Muslim notions of femininity and masculinity as the focal point of cross-cultural dialogue.

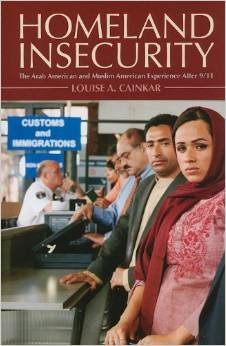

Louise Cainkar, an assistant professor of sociology at Marquette University, recently published a book in which she argues that, while anti-Muslim suspicion existed prior to 9/11, 9/11 created an environment in which hostility toward Muslims could thrive and their political and social exclusion could be legitimated by both the government and nativist Americans. While Cainkar’s discussion in her book, Homeland Insecurity: The Arab American and Muslim American Experience After 9/11, is, as a whole, thoroughly fascinating, if not depressing, her research regarding gendered dehumanization stands out as especially troubling – though also suggestive of where we may find solutions. Cainkar’s dissection of the gendered patterns of dehumanization identify gender as a critical area for cross-cultural dialogue. She lays out three patterns in particular of gender dehumanization.

Women in hijab as symbols of anti-Americanism

As is perhaps inevitable, after 9/11 Muslim women who don hijab (the headscarf worn by some Muslim women) became central to the construction of Arabs and Muslims as the ominous “Other” – that is, as belonging to a culture in which women are oppressed and incapable of exercising choice, and men are violent and misogynist. No woman could possibly choose to wear the hijab, or perhaps more accurately, a woman could not legitimately exercise choice when it came to something like the hijab, which represented a revolt against American values. Those forced to wear it and those who chose to wear it were both acting in a manner unacceptable to the American way. By obliterating choice with regard to the hijab, these social constructions essentially debased the free will of Muslim women.

Saving Muslim women from these purportedly oppressive garments became a theme used to invoke support for the U.S.’s war in Afghanistan. Those who supported the war, justified the need for the invasion by pointing at images of Afghani women shrouded in all-encompassing, billowing blue burkas, sometimes seen being publicly beaten and executed by the Taliban. The government’s construction of women in hijab as symbols of barbarism made them counter-symbols to American freedom. The localized effect of such a construction: some Americans – self-fashioned “defenders” of American values – wanted to kick out women who wore hijab from their neighborhood.

Interestingly, the same set of notions that posited women in hijab as the opposite of freedom construed the chastity of Muslim men as equally foreign and threatening. “Muslim women were perceived as forced to cover their hair, just as Arab/Muslim men were perceived as forced into sexual sublimation.” (256) Muslim men’s not being allowed to view female flesh, or enjoy sexual intimacy outside of marriage, militated against the nativist idea of freedom, and for this, Muslim men were made the enemy.

Muslim women: Producers of terrorists

While the belittling of Muslim women in hijab may be a familiar concept, a less known phenomenon highlighted by Cainkar is that of Arab and Muslim women as producers of terrorists. This was an attack on Arab and Muslim motherhood, alleging that Muslims are cold and unloving toward their children, thus predisposing them to terrorist behavior as adults. Cainkar quotes Howard Bloom’s 1989 article, The Importance of Hugging, from Omni magazine to highlight the types of arguments commonly restated by nativists in the post-9/11 climate:

Could the denial of warmth lie behind Arab brutality? Could these keepers of Islamic flame be suffering from a lack of hugging? … In much of Arab society the cold and even brutal approach to children has still not stopped. Public warmth between men and women is considered a sin. And the Arab adult, stripped of intimacy and thrust into a life of cold isolation, has become a walking time bomb. An entire people may have turned barbaric for the simple lack of a hug. (243)

According to Bloom, the lack of public displays of affection between grown Muslim men and women signal a lack of warmth between parents and their children. The total absence of logical consistency in Bloom’s argument is jarring.

Bloom was not alone. The Global Ideas Bank, relying on Bloom’s work, argued:

The cultures that treated their children coldly produced brutal adults, according to a survey of 49 cultures conducted by James Prescott … Prescott’s observations apply to Islamic and other cultures, which treat their children harshly. They despise open displays of affection. The result, he claims: violent adults. (243)

Bloom-like arguments about the barbarism built into Arab and Muslim culture – sinking as low as questioning Muslim motherhood – have been employed in the cultural front of the War on Terror. Muslim women, as reproducers of culture, have thus found themselves frequent targets of this tactic of attack by nativists, or those seeking to protect the “American way of life.”

Gendered emasculation of Muslim men

Muslim women are not the sole scapegoats of nativist slander; Muslim men shared in the suffering. Cainkar explains that in times of crisis, when nationalism is mobilized, “men and women are expected to conform to hegemonic definitions of masculinity and femininity.” (244) In the post-9/11 process of determining what characterized an American, attacks on Muslim women who donned hijab amounted to an attack against those who did not fit this hegemonic concept of femininity. For Muslim men, the process was a bit more convoluted. Because they did fit the hegemonic conception of masculinity, rejecting them required that they be made not to fit; essentially, they had to be feminized. As such, Muslim men were stripped of their masculinity – the degradation ceremonies perpetrated against Arab and Muslim men imprisoned at Abu Ghraib were emasculation rituals.

While Muslim men at Abu Ghraib experienced a direct form of emasculation, Muslim-American men suffered from a more subtle form. These men were not afraid of the type of neighborhood attacks Muslim women faced, but instead felt unprotected by the rule of law, particularly in small towns where unregulated, abusive detention could be carried out more easily than in urban areas. “They feared being beaten, being detained, and being moved from place to place while multiple agencies searched for records of illegal activity, suspicious contacts, or ties to terrorism, and they feared that, in the process, no one would know.” (259) Muslim-American men were and still are to some degree subject to detention without adequate cause or explanation, and once detained, are made completely powerless. This implied emasculation is tied into larger hegemonic notions of masculinity and who is allowed to fit that image. If, in times of crisis, men and women are expected to conform to hegemonic definitions of femininity and masculinity, and if Muslim men are seen as the enemy and cannot be allowed to fit this definition, it becomes necessary to strip them of their masculinity. As this is not an easy process that can be undertaken by neighborhood crusaders, it must be done through “government actors with powers of detention.” (233)

The way forward

In the years since 9/11, Muslim men and women have responded to nativist hate mongering by working within the American legal framework. Muslim women have made the hijab a civil rights issue; similarly, the fight for the human rights of detainees has been going strong for some time.

An additional response – one that is more nuanced to the gendered aspects of the problem – is to use gender and Muslim notions of femininity and masculinity as the focal point of cross-cultural dialogue. In times of crisis people revert to hegemonic definitions of masculinity and femininity and this suggests that there is something about gender and sexuality that is fundamentally linked to national identity. There is something about gender that helps the dehumanization process in times of crisis. It seems, then, that in times of [relative] peace, efforts should be made to explore those connections in a way that prevents the crisis impulse to dehumanize the other.

The inherent femininity of Muslim women who wear the hijab is thus a theme to be explored, as is the seeming “foreignness” of the hijab. Are there ways to make non-Muslim Americans understand the hijab as essentially American? Are there ways to argue for femininity within the framework of Islamic modesty, in a way that non-Muslims can understand?

As for Muslim men, much of nativist fear is rooted in the idea of Muslim men as forced into sexual sublimation, that is, unable to view female flesh or act on their lust outside of marriage. Nativists perceive Muslim men’s modesty in this regard as a threat. Can peacetime dialogue change this conception? Is there a way that male chastity can be explained for its voluntariness, and perhaps even for its inherent masculinity?

Often, cross-cultural dialogue revolves around generalities, focusing on the minutiae of religious history and ritual or varying cultural practices. Broad-based, but deeply probing, discussions on notions of masculinity and femininity and the ways these notions are shared, and cherished, by Muslim and non-Muslims alike, may be more effective in paving the path forward. In place of imposing Muslims concepts of modesty on Americans, or American concepts of freedom on Muslims, cross-cultural dialogue should explore the connections and intersections. That is, it should explore how Muslims who choose to be modest are “free” in a very American way, and how American and Muslim notions of modesty are fundamentally connected rather than diametrically opposed to each other.

Asma T. Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah.