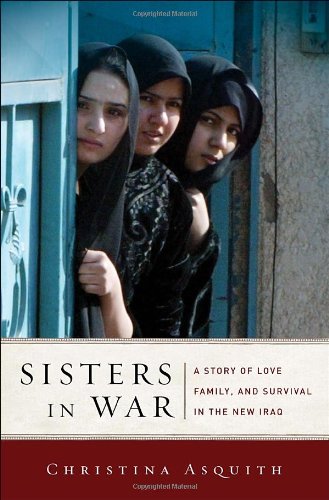

Journalist Christina Asquith’s new book Sisters in War: A Story of Love, Family, and Survival in the New Iraq tells the story of four women, their internal growth and external accomplishments, all of which give the reader a balanced, multifaceted look into the realities of post-war Iraq, including the failures, incompetency, oversights, and hubris involved but also the small successes and the opening of new opportunities.

Few books capture the complexity and diversity of Muslim women and the varying views on their place in Islam as Sisters in War: A Story of Love, Family, and Survival in the New Iraq by journalist Christina Asquith. Sent on assignment to Baghdad in 2003, Asquith later takes refuge in the home of two Iraqi female friends as the threats against Western journalists increase. Her experience provided her with an up-close and personal account of four women: Zia and Nunu, a young Shi’a Iraqi risking her life to work on an American military base to support her family and her college aged-sister determined to finish school, respectively; Heather, an Arabic-speaking U.S. army reservist frustrated by the military’s chain of command; and Manal, a Palestinian-American NGO worker. These are stories of Iraq’s reconstruction rarely heard until now.

Asquith, an award-winning journalist and author of The Emergency Teacher, begins the book with Zia and Nunu, who have left their home in Baghdad to stay with their Sunni relatives in a village one hundred miles outside of the city as they await the U.S. invasion. As the sisters rejoice over the opportunities to follow in post-Saddam Hussein Iraq, their relatives are weary of the international troops and saddened by Hussein’s soon-to-be toppling.

The book references the history of women’s liberation in Iraq and Hussein’s early popularity, which dissipated after he began assassinating Shi’a clerics, banning religious gatherings, and dragging the country through years of hardship as it engaged in war with neighboring Iran. As the country suffered, Iraqis were hopeless to stand up for change since speaking out against Hussein’s policies was punishable by torture and death. After the imposition of the United Nations sanctions, Iraqis became further crippled and women’s rights further diminished, with fathers being forced to marry their daughters at younger and younger ages – a far cry from the days when women went abroad to study and served as prominent doctors, professors, and lawyers in Iraq.

Against this backdrop, Asquith plunges into the stories of her four main characters. Unconvinced that the U.S. army had any understanding of Iraq’s history and complexity, Manal, a Palestinian-American women’s rights activist who knows that change must come organically, from the Iraqis themselves, reluctantly teams with Heather, a U.S. Army reservist. Despite her lack of experience, Heather has been granted millions of dollars from the U.S. government and international aid agencies. Together with Manal, Heather has big dreams of opening a multitude of women’s centers and helping establish a female quota in parliament.

However, in contrast to the likes of former First Lady Laura Bush praising the Bush administration for advancing the rights of Iraqi women, Asquith describes the reality on the ground: little progress is ever made throughout the course of time the Americans are present in Iraq. Instead, there is tremendous carnage and conflict. Manal’s and Heather’s plans fall apart as they face endless physical and cultural obstacles. One by one, moderate Muslim women leaders are killed while the more conservative Iraqi women with extreme views often dominated by rural male tribal leaders get elected instead. Standing up for women’s rights, even if it means prosecuting a man for an honor killing, becomes a death sentence.

Even female translators working on Iraq’s reconstruction with the Americans are considered abominable, infuriating to those who prefer to keep women inside and locked away. As one murderer bragged to Zia, reflecting the prevalent sense of justification and pride in eliminating such women, “These translators are whores. I just killed two last week and I’m following the third … The second one I killed while she was with the Americans. The bullet went through her heart; she was standing there translating and all of a sudden she fell down.” (140)

Despite these risks, Zia decides to work for the Americans, first as a translator for the American-run Iraqi Media Network (IMN) and later as a facility manager for the U.S. Embassy. While working there, the twenty-something Zia meets and falls in love with Keith, a fifty-year-old American man. Weaved among the stories of suicide bombers, bureaucratic incompetency, and the increasingly sad state of women’s rights, is Zia and Keith’s love story, itself riddled with endless complexities. Through Zia, we learn how many Americans, like Keith, are in Iraq as an escape from their problems back home: estranged wives, children who feel neglected, and an overall sense of failure.

Eventually, as Zia’s life becomes unbearable in Iraq, she manages to escape first to Jordan, where she is barely able to meek out a living, then to America, where Keith eventually joins her and marries her. While Zia is settled in America, her family back in Iraq finds itself hopelessly lost in Iraq’s cycle of destruction. Nunu is afraid to even attend school, as she is groped in public on her way home one day, openly harassed because she refuses to veil.

Left with nothing to do, Nunu finds herself first depressed, and then feeling nothing at all – a total numbness overtakes her. In her landscape of dying neighbors and fleeing friends, the only thing that manages to further horrify her is the series of marriage proposals that come her way, each time from a more heinous or pompous man. The extreme state of affairs, however, manages to finally shake her, as it dawns upon the domesticated, complacent Nunu that she is capable of so much more than that. From utter numbness arises a Nunu that is stronger and more resilient than ever; as she writes in her journal, “Many suitors ask for my hand but I refuse them because I refuse to be treated as a slave or belittled. No, I refuse such a reality. I am a woman, yes, and I am proud of being a woman, and I don’t have anything to be ashamed of.” (317)

In coming to such a realization, Nunu toward the end of the book ends up in a psychological place similar to the other female characters. Like Nunu’s sister Zia, Manal and Heather are also headstrong women with big plans and determined spirits. Manal, a woman who voluntarily donned the hijab against her mother’s wishes, grew up questioning life and found the best answers in her faith. Divorced at an early age, she has firsthand experience of an unhappy marriage, and, once divorced, relishes her freedom.

Heather, on the other hand, is not only happily single but is adamant on staying that way, shocking her Iraqi colleagues with her determination to never be married and never have kids. Despite facing sexism in the military, Heather enjoys her work and left a cushy government job to take on the dangers of working in Iraq.

The stories of these four women, with their internal growth and external accomplishments, gives the reader a balanced, multifaceted look into the realities of post-war Iraq – the failures, incompetency, oversights, and hubris involved but also the small successes and the opening of new opportunities. Asquith’s book, a true page-turner, reads like a novel while sharing a perspective on Iraq rarely accessible to the American public.

Altmuslimah spoke with Christina Asquith about Sisters in War. Here’s what she had to say about lessons learned and her faith in future progress:

![]() What was your motivation in writing this book?

What was your motivation in writing this book?

Christina Asquith: After I came back from Baghdad, I realized that while we were inundated with stories about war, Iraqi women’s lives had been overlooked. Most war correspondents are male and Iraqi women will not talk to them openly. Yet I had been able to really get to know many women and understand the very personal ways in which the war was affecting them. One woman tried to escape her husband and work for the Americans, only to come under death threat for “collaborating with the infidel.” Another woman couldn’t continue her education because the university had been overrun by Shia militants who forced women to veil. Many women were trapped in their homes due to the lack of security; they couldn’t work, shop or enjoy time outside. For young women, at an age where they are looking for husbands, sitting at home all day for years became unbearable. Women complained that they were less free under US occupation than they had been under Saddam. I realized a tremendous part of the experience of the war was not being told and I wanted to tell it.

![]() What were things you learned from the experience, as a writer and personally?

What were things you learned from the experience, as a writer and personally?

I spent five years covering the lives of the women in my book. The first year in Iraq I spent going to women’s conferences and talking to officials and female politicians. Then, I began to get to know specific Iraqi women. I even moved in with the family in my book, and saw how they lived. It was Ramadan and I woke with them before sunrise to eat. I tried to fast. I listened to their stories about life under Saddam. Through this experience, I really came to understand the strength of their faith. I read many histories of the Arab world, as well as the Koran and we discussed the passages on women; and I came to understand concepts like Sharia and Sunnah, as well as the history of Sunni and Shia. Soon, I knew more than many of my Muslim friends, although I realize that there is still so much more to know. What I really learned, though, was how important it was for a journalist to educate themselves before they begin writing about something.

![]() In terms of mending the divide between Islam and the West, particularly in regards to women, how much faith do you have in this being a possibility?

In terms of mending the divide between Islam and the West, particularly in regards to women, how much faith do you have in this being a possibility?

I have a lot of faith that this is possible, especially under the Obama administration with Hillary Clinton heading the State Department. The U.S. went into Iraq promising to empower women; yet most of their efforts to do this were unsuccessful because projects were implemented by Westerners or U.S. soldiers, with no expertise on Iraq and few contacts among the locals. They didn’t know what Iraqi women wanted. In my book, I describe how the U.S. earmarked several million dollars to build fancy women’s centers across the country. However rather than become the vehicle with which women organize, the centers became lightening rods for anti-Western insurgents, who were convinced all sorts of nefarious activities went on inside. One center was bombed within months of being opened. The women stopped coming, and all that aid money was wasted. Meanwhile, there were many small, Iraqi women’s groups working in health, education and jobs training that never received any funding. The lesson going forward is to let Iraqi women lead the way and decide what is best for themselves. Fund Iraqi groups, not Western groups in Iraq. Most Iraqi women in Iraq want the same things as Western women: peace, economic security, families and a future for their children. If you support them, they will succeed in achieving these aims.

Asma T. Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah. Rahilla Zafar is a Contributing Writer to Altmuslimah.

When is it going to hit our collective consciousness, that progress is not going to come from and American administration or a non-Muslim feminist. Progress is going to come when we as an Ummah make authentic Islamic progress our personal mission. We are still strapped to the confines of moral convservatism, and an unpromoted value system. Only when actual guardianship of the Deen is undertaken by progressive minded people of intellectual and moral integrity will we be able taste the fruits of progress. Guardianship of everything our Fiqh to our Silsilas, history and art.. to the protection of our fellow brothers and sisters. If the sacrifice constantly comes from an agnostic westerner or a christian missionary, then the benefits will be theirs and we will suffer along with our Deen.