Look, Juan, I’m not an apologist. But I am an American woman who chooses to wear that ‘Muslim garb’ on planes … and also at school, at work, to the grocery store, the library, the shopping mall, at the park, on the metro, in line to get lunch, or coffee, or a movie ticket. When I enter an airport, or step out of my car at a gas station, or go jogging on the street, I’ve got to tell you, I realize that I am in Muslim garb and I think, you know, I am identifying myself first and foremost as Muslim, I get worried. I get nervous.

Look, Juan, I’m not an apologist.

But I am an American woman who chooses to wear that ‘Muslim garb’ on planes … and also at school, at work, to the grocery store, the library, the shopping mall, at the park, on the metro, in line to get lunch, or coffee, or a movie ticket.

When I enter an airport, or step out of my car at a gas station, or go jogging on the street, I’ve got to tell you, I realize that I am in Muslim garb and I think, you know, I am identifying myself first and foremost as Muslim, I get worried. I get nervous.

I realize that my identity-marker triggers a Pavlovian aversion among the public; conditioned by the right wing rants of FOX and friends and their attempts to incarnate a public solidarity through the shared experience of fear. ‘First and foremost as Muslim’ has become linked to images of death, destruction, and apocalyptic doom.

But ‘first and foremost as Muslim’ is what gives meaning to my life devoted to truth, and mercy, and justice, what constantly affirms my commitment to the common good and the public welfare.

‘First and foremost as Muslim’ is what empowers a more expansive understanding of self, what confronts that self-interested rational actor in me and challenges it to be a loving actor.

‘First and foremost as Muslim’ is what holds the center together so things don’t fall apart – it is the call of the falconer drowning out echoes of nihilism amplified by the chamber of modern life.

Your colleague at FOX, Megyn Kelly, came to your defense saying “a lot of Americans share Juan’s view and it doesn’t make them bigots, it makes them honest”. Rather than devote airtime unpacking the substance of these fears in an honest way, our public servants and our media platforms instead choose to expend their influence defending the right to wallow in those admittedly problematic feelings. I don’t deny that the language of fear can effectively herd people together, but it does not empower them.

Your individual right to express feelings of fear cannot be challenged, and NPR’s decision to terminate your contract does not deny that. What it does deny is the extension of a professional accreditation and a journalistic objectivity that makes those views seem legitimate, justifiable, or simply benign. Your right to declare feelings that prop up xenophobic ideologies is stripped of the rhetorical force that would justify the feelings of ‘a lot of Americans’ by putting them in good company.

The truth is, in America today; in our country which protects our rights to life and liberty, our rights to equal protection under the law, your right to normalize the fears directed at me, and my right to write a response reminding of their abnormality; I still get worried, I get nervous. Because even honest fears, left unchallenged, can embolden the voices and actions of bigotry; and my ‘Muslim garb’ makes me an easy target. Surely you can appreciate the circular chase between our fears.

I know the kinds of books you’ve written about the civil rights movement in this country, and I recognize our shared aspirations for the future of our nation. You write,

“The American idea is unique: creating one nation out of so many people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, who speak different languages, who have different skin colors. It is an experiment in how these people, often facing brutal discrimination, stand up to ask for equal opportunity and make their contribution to American life. At the heart of this drama is a personal struggle: how to deal with the fear engendered by living in a country with people from all over the world.” (2004)

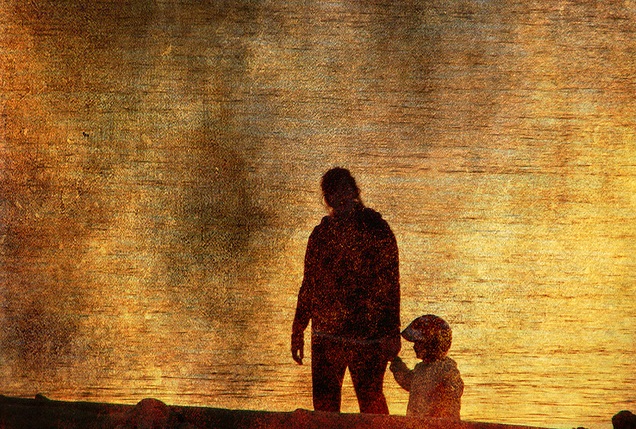

We can begin to deal with this fear by conceding that its legitimation does not strengthen us. We must search elsewhere for common ground. Only by approaching ‘the other’ and seeing his/her humanity, can we realize that beneath the outer garb that differentiates us, he/she shares our very dreams of the American promise.

(Photo: John Rewrite)

Aisha Saad is currently a Rhodes Scholar studying at Oxford University. She is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.