If Herman Hesse were alive today, he’d fall in love with Lyrics Alley, a story that resonates with the theme of his famous short story The Poet: the solitary life and mission of the poet. But Leila Aboulela’s novel depicts that theme with arguably more intrigue, depth, and complexity, as it tells its story of self-determination, fate, love, and the intrinsic value of art. The novel takes place in the Sudanese city of Umdurman in the early 1950’s, which was a critical time in Sudanese history.

Very important events were taking place, with many other tidings in the horizon; the British mandate was coming to an end; King Farouk, the king of Egypt and Sudan, was overthrown; and the alliance with Egypt appeared to be falling. The novel tells the story of a family who lived during that critical time, the Abuzeid family, led by the bright businessman Mahmoud Bey, whose factories and investments were already shaping the country’s economic future. The family is portrayed as the most prestigious and wealthy in Umdurman, and one of the most well-known families in Sudan.

At the center of the story and this family is Nur Abuzeid. At the prime of his youth, when all around him marvel at his exceptional talents and promising future, an accident leaves Nur paralyzed, unable to move any limb of his body. The young man becomes heart-broken and tortured by the loss of the life he could have had. He loses hope of a full recovery, taking with it his dreams of going back to Victoria College and then to Cambridge University; then, he loses the love of his life: his first cousin, Soraya, who marries his very best friend, Tuf Tuf. The question of “why bad things happen to good people” haunts him endlessly after the accident. He seems to have lost faith in the justice of life, especially when he compares himself to his older (healthy) brother, Nassir, the disgrace of the family who is hardly ever sober, and always appears to be wasting the family’s money on his lavish parties. Ustaz Badr, a poor Egyptian teacher of Arabic, and Nur’s tutor, ponders that same question after his continuous misfortunes as well. Yet Badr seems to be the one who knows the answer to that question (or strongly believes he does); his talk about how God tests the patience of the ones He loves most through suffering seems to have been proven true in his case and in Nur’s as well. Badr’s troubles bring him closer to the Abuzeid family, who make his dream of having his own apartment in Undurman’s first tall building come true. Similarly, Nur’s patience and will to live is rewarded with his major success in becoming a famous poet, and the talk of the town; he is able to find peace and satisfaction through the power of art and poetry that lies within him.

Through the broader story of the Abuzeid family, Lyrics Alley also sheds light on the Sudanese people’s conflicting schools of thought at that time. The upper-class (businessmen, investors, and politicians) are shown to be in favor of the British presence and the laws imposed by the Anglo-Egyptian government, which of course benefit their businesses; Mahmoud Bey’s friendship with the Harrisons of Barclays Bank sets a perfect example of this perspective. In contrast, the middle- and the lower- class resent the foreign presence, and call for Sudan’s independence.

Another revealing conflict in the story is between traditional and modern worldviews. Mahmoud Bey’s wives Waheeba and Nabilah demonstrate this conflict for the reader. Waheeba (also known as Hajjah Waheeba) is Mahmoud’s first (now estranged) wife, and is three years his senior. As an old Sudanese traditional hajjah with tribal marks on her cheeks, Waheeba is viewed as illiterate, superstitious, and stubborn. She supports female genital mutilation, a practice she would insist upon despite her own husband’s disapproval. She does not trust modern medicine, and wants her son, Nur, to be treated by a faqir (Sufi ascetic), due to her suspicions that his predicament is only the result of a curse of “evil eye.” On the other hand, Mahmoud’s second (Egyptian) wife, Nabilah, is everything his first wife is not: beautiful, well-read, well-travelled. She represents the open-mindedness of the younger generation through her support for art and women’s rights for freedom and respect. But still, she is not perfect: she feels superior to all the people of Sudan, including her husband; she boasts how Cairo is heavenly when compared to the “god-forsaken” Umdurman or Khartoum, with their “backward” people. The conflict between traditional and modern is not necessarily generational, though; the father, Mahmoud Bey, is very open-minded and modern, especially when compared to his younger brother, Idris.

All in all, Ms. Aboulela has written an intriguing novel that is a delight to read. The convincing, well-developed characters; spontaneous, beautiful language; well thought-out images; and the book’s rich examples of traditional and cultural aspects of everyday life in 1950’s Sudan make this novel a must-read.

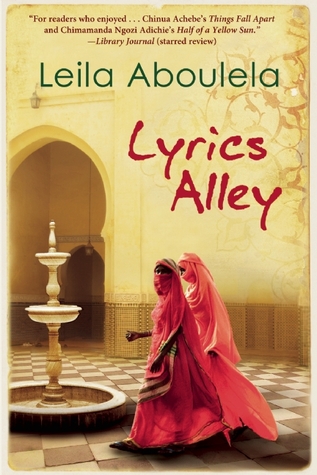

(Photo Source: Goodreads)

Ahmad Ghashmary is a contributing writer to Altmuslimah.