The monkey and the crocodile. My father used to tell me that story when I was very young. But the version he told me was different from the tale I told Sadiq. In my father’s story, the crocodile is put up to the betrayal of his friend, the monkey, by his greedy wife. She deceives him, feigning illness to get him to do what she wants–to bring back the monkey’s heart for her to eat so that she might become well. Same ending, though. When I was eight or nine years old, older than Sadiq was when he was taken from me, I told my father that I didn’t like his story.

I said, “That’s not right. The crocodile himself made the decision to kill his friend. Why should his wife be blamed? Women are always the ones being blamed for everything!”

My father laughed. “Oh? So this is a subject you’ve given some thought to?”

“Yes. When a man is bad to his mother, it’s his wife’s fault. When a man is bad to his wife, it’s his mother’s fault. When is a man ever responsible for himself?”

“Hmm. This is a very good point. People tell stories. And people listen to them. The way a story is told says something about the one who tells it. And the way it is understood, the lesson drawn from it, tells something about the one who listens. How would you tell the story, Deena?”

“Me? I would say that the crocodile himself was greedy. That he was never really the monkey’s friend. He only liked her for the fruit she gave him.”

“Ah. But I don’t like your version.”

“You don’t?”

“No. For me, the beauty in the story is that the crocodile and the monkey were able to be friends, even if for a brief time. That they rose above their own natures and the way they had been taught to live–to live by fear or to live by greed–and became friends in spite of it ll.”

“But their friendship didn’t last.”

“No. That doesn’t matter. They were friends for a time. For me, that is such an important part of the story that I’m not willing to change it.”

I was quiet for a long time. Then I said, “All right. What if it’s the crocodile’s brother who tempts him?”

“His brother, eh? All right. That I’m willing to accept. That is the new tale of the monkey and the crocodile. Deena Iman’s version.”

“And yours.”

“Oh? You’ll share credit with me? So kind of you, little Deena. All right then, Deena and Iqbal Iman’s version of ‘The Tale of the Monkey and the Crocodile.’ Shall we tell it together? Yes? I’ll begin…Once upon a time…”

And so it began. My father and I, together, gave each other permission to change old stories, to challenge old ways of understanding. Monkeys and crocodiles. Fear and greed. Who hasn’t succumbed to those old temptations? And how many can claim to have risen above them?

When I was nine years old, I used to spend time on the terrace of our house. There was a jamun tree in the neighbor’s garden. You are nodding. Sadiq told you about the tree? Well, remember, I am speaking of a time long before he was born. The tree was younger then, not so tall, its branches not so wide, as when Sadiq knew it, its fruit spread from branches that shaded one corner of the terrace, within easy reach for him as it was not for me. When I was a child, the top of the tree was level with the top of the low wall of the terrace. To get any fruit, I had to lean down at a dangerous angle, to reach for the one branch that stretched out to meet my grasping hand. That didn’t stop me. The fruit was tasty enough to make the risk worth it. One day, when I had already consumed all of the fruit from the tip of the branch, I leaned farther than I should have, too much of my weight hanging over the wall, and gravity had its way. As I lost my balance, in the second before I fell, I heard someone call, “Look out!” A child’s voice, from the garden below. The voice of someone who was there–in the right spot at the right time–to break my fall and save me from certain death.

***

That was how our friendship began. We were only children. Neighbors. Young enough for it to be all right, despite the fact that he was a boy and I was a girl, he a Sunni and I a Shia. Even so, there were limits we knew enough about already for us to keep our interaction secret–or try to, at least, though we had no chance of succeeding, considering that the volume of our interactions had to accommodate the distance from my terrace to his garden, and that there was no real way to hide from these vantages, despite the constant ducking I grew accustomed to. Once, I ducked late enough to catch a look on his mother’s face–cold and hostile, enough to make me want to keep ducking.

Normally, Umar’s afternoons would have been like those of the other boys in our neighborhood. As a boy, he would not have been confined to the boundaries of home. Boys could spend their time in the street. Riding bicycles and playing cricket. Umar was still young, so he would not yet have been allowed to travel far, by bus and rickshaw, to the movies and around town, like other, older boy in the neighborhood. Without my parents, I went only to school and back–by horse carriage, no less–a two-wheeled tonga, with a driver contracted for that purpose, always accompanied by Macee. My world, a girl’s world, was smaller than his.

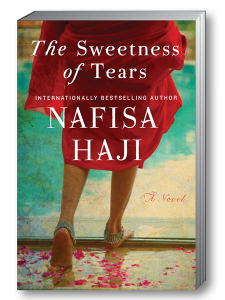

Nafisa Haji is author of the new book The Sweetness of Tears (HarperCollins), which was published in May 2011. Nafisa Haji’s first novel, The Writing on My Forehead, was a finalist for the Northern California Independent Booksellers Association Book of the Year Award. An American of Indo-Pakistani descent, she was born and raised in Los Angeles and now lives in northern California with her husband and son.