No less than seven people told me that I had to watch the television show Humsafar. My Pakistani-American cousins and friends, who have so overlooked the cultural exports of their motherland in the past, seem to have attached themselves to this particular drama. Indeed, it has taken the Urdu-speaking world by storm. Not only are Pakistanis obsessed with it, but also with the help of YouTube, it has gained tremendous popularity in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

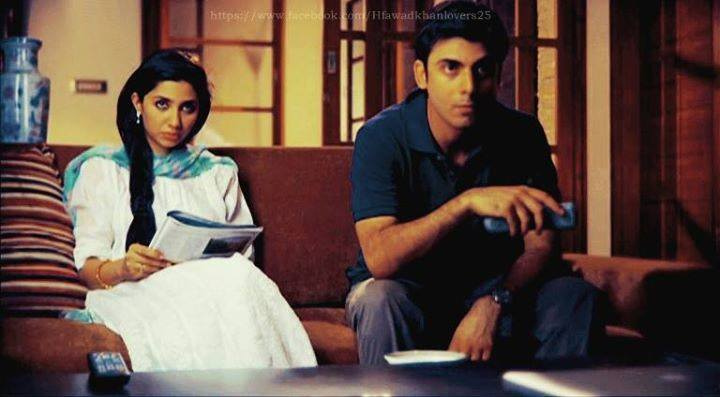

Humsafar, which translates to “soul mate” in English, is based off of an Urdu novel of the same title by Farhat Ishtiaq. Centering on a love triangle, the show revolves around the misfortunes of Khirad, our protagonist, who is forced to marry her cousin Asher at her mother’s deathbed. Khirad and Asher eventually learn to love one another, but determined to destroy their relationship is Asher’s childhood friend Sarah. Sarah joins forces with Asher’s mother, Fareeda, to dissolve their relationship, resulting in a pregnant Khirad being forced out of her home. As the show approaches its finale, viewers wait with bated breath to see if Khirad and Asher will be reunited again.

In the midst of all this are the very real tensions between social class: Khirad portrays a middle class upbringing while Asher and Sarah live in homes with indoor pools and imported furniture. It is exactly Khirad’s upbringing that annoys Fareeda and Sarah most, and it is the reason they wish to drive her away from their life. Often referring to her as a “two-room girl”, a girl raised in a two-room apartment in the less wealthy Hyderabad, Fareeda sees Khirad as less worthy and possibly even less human because of her social class.

More fascinating is the commentary the show seems to make on female relationships. Though the show may mask itself as a love story between Khirad and Asher, women mostly advance the plot. Asher’s father dictates Khirad’s marriage to Asher, but even then at the insistence of Khirad’s mother. Meanwhile, Fareeda and Sarah plot in the background for Khirad’s demise. And ultimately, what brings together again our star-crossed lovers is their daughter, Hareem.

The show is almost formulaic: the classic saas-bahu (mother-in-law/daughter-in-law) dynamic, a Cinderella-like experience for our protagonist, and, as with most Pakistani drama serials, high-level Urdu dialogue. In fact, this is what Pakistani dramas are known for: a basis in Urdu poetry that is the pride of Pakistan’s culture. Humsafar’s theme song exemplifies this as it makes its own appearance throughout the drama:

“When we parted ways,

Neither you cried nor I.

But, what is this,

A peaceful sleep since

Has not touched our eyes?

He was my companion,

But not in harmony were we.

Like the clouds and sunlight,

Together but as apart as can be.

There were feelings of animosity,

Indifference,

And anguish between us,

My departed lover had been everything,

But unfaithful.

Last time I looked into his eyes,

My poetry reflected back at me,

Verses that I had never

Recited to anyone.”

Pakistan cannot compete with multi-million dollar film releases by its neighbor Bollywood, though it has tried with large production films like Khuda Kay Liye and Bol (both of which include in their casts actors who appear in Humsafar). This may very well be part of Pakistan’s cultural revival: a return to the Urdu poetry of the past with the achievable goal of well-produced scripted television.

And much like Downton Abbey for the Brits, Pakistanis are overwhelmingly proud of Humsafar’s success. After years of importing American entertainment, restaurants, and fashion, Pakistan is able to export something other than bad news. And also like Downton, the show focuses on the central themes of all good television: unrequited love, climbing the social ladder, and heartache.

This provides the exact recipe required for a hooked viewership, which will be watching Humsafar until it’s finale in a few short weeks.

Hafsa Arain was born in Karachi, Pakistan, and raised outside of Chicago. A graduate of DePaul University with a degree in English literature and religious studies, she is a creative nonfiction writer and interfaith activist. First published at age nineteen, her work has been featured on The Washington Post, CoLab Radio at MIT, among other places.