The debate about whether Canada’s “Shafia murders” were “honor killings” or “domestic violence” seems like an argument about whether “■” is a square or a rectangle. Beneath the surface, however, much more than semantics is at stake. Critics who reject all mention of “honor” have legitimate grievances about the language we use to discuss these crimes, but their reaction is misguided. We should not blame violence against women on culture alone, nor should we ignore the role that culture plays in enabling it.

In June 2009, police found the bodies of three teenage girls and a middle-aged woman in a submerged car in Ontario, Canada. The girls—Zainab, Sahar and Geeti Shafia—were daughters of a wealthy Afghan immigrant named Mohammed Shafia; the fourth victim, Rona Mohammed, was one of Mr. Shafia’s wives from a polygamous marriage. When investigators placed Mr. Shafia under surveillance, they were shocked to discover that instead of mourning the loss of his children, he cursed them for disobeying him and called them “whores” for dressing provocatively and having boyfriends. Police eventually charged Mr. Shafia, his second wife Tooba Yahya and their son Hamed with four counts of first degree murder, and a jury convicted them on January 29th, 2012.

An “honor killing” is the murder of a person who “dishonors” their family by violating certain cultural norms (or getting accused of doing so). These killings are arranged by the victim’s family (or community) in order to “cleanse” the dishonor, and are often heavily premeditated. The Shafia murders attracted an enormous amount of attention because they seemed to fit this description.

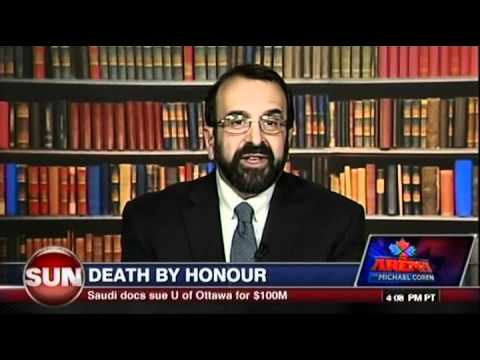

Anti-Muslim commentators seized on the Shafia trial as an opportunity to bash Islam. Pamela Geller, famous for her virulent opposition to the “Ground Zero Mosque” in 2010, called the slayings “Islamic gendercide” and “religious slaughter.” Robert Spencer claimed that honor killings were justified in Islam, and Canadian pundit Ezra Levant described honor killings as a “war on Muslim women.”

Muslims made swift efforts to distance these crimes from Islam, but some of their responses only reinforced the perception that religion was to blame for what happened. Canada’s most famous Muslim author, Irshad Manji, explained that honor killings were “not Islamic,” but then called them “a problem within Islam.” Meanwhile, Imam Syed Soharwardy issued a religious edict (or fatwa) against honor killings on behalf of the Islamic Supreme Council of Canada. Soharwardy’s edict is commendable, but it could give the false impression that honor killings are a problem of scriptural interpretation (especially considering that he presented it by saying, “So if anybody is thinking that honor killing is allowed in Islam…”) There is no evidence that Mohammed Shafia believed this.

The Canadian Council of Muslim Women (CCMW), like others, has asserted that the Shafia murders were not religiously sanctioned. It stands out, however, for its criticism of the term “honor killing.” CCMW director Alia Hogben argues that the Shafia victims died “simply because they were females,” and that honor or dishonor was not a determining factor. Echoing this sentiment, anthropologist Homa Hoodfar and communications scholar Yasmin Jiwani insist that the killings are “about women and girls being killed because they are women and girls. That is the particularity of this kind of violence.” These analyses ignore the role that “honor” may play in such crimes—which seems bizarre in light of Mohammed Shafia’s rants about honor and the casual admission by Tooba Yahya’s relatives that they would put their own daughters “in a bag and eliminate them” for dishonoring the family.

Hogben rejects the term “honor killing” because, she argues, the language frames the murder of women as a cultural practice—which encourages both racism and cultural relativism. The Canadian Council of Muslim Women suggests that the term functions to “separate [people] into distinct groups based on race, culture or religion.” This mirrors the prevailing attitude toward collecting statistics on religion in France, where, according to political scientist Sepideh Farkhondeh, “the refusal to consider religion as part of the public sphere becomes equivalent to a refusal to know and understand [Muslims].” Similarly, the refusal to consider the cultural elements of honor killings is a refusal to know and understand these crimes.

It is easy to see why people are wary of the term “honor killing.” Most discussions of these crimes are painfully obtuse and abound with clichés about “ultraorthodox Islam” and the “medieval.” And even when commentators refrain from blaming religion for honor killings, they tend to speak of “culture” in ways that confirm racist stereotypes and overlook violence against women in “Western” societies.

Legal scholar Leti Volpp (2001: 1186) observes that most people “identify [violence against women] in immigrants of color and Third World communities as cultural, while failing to recognize the cultural aspects of [violence] affecting mainstream white women.” This grievance seems to be the cause for most complaints about the term “honor killing.” According to Hoodfar and Jiwani, for example, the phrase “makes it seem as if femicide is confined to specific populations…and specific national cultures or religions.” The Canadian Council of Muslim Women alleges that it “makes these murders exotic, foreign, and alien to Western culture as if the West is free from all forms of patriarchy” (emphasis added).

The real problem for these critics is not that cultural dimensions of violence are being recognized, but that they are recognized selectively. They are right to condemn this imbalance, but their solution—to equally ignore the cultural aspects of all violence against women—is unacceptable.

Culture can be defined as learned patterns of speech, thought, and behavior that prevail within a group and are acquired through social participation. Religion scholar Zareena Grewal (2009: 12) cautions against blaming violence on culture alone, but also argues that it is “wrong to ignore or suppress the cultural particularities that may characterize acts of violence or to talk about violence only in the abstract.” This is because, as sociologist Johan Galtung (1990: 291) explains, certain cultural norms can “make direct and structural violence look, even feel, right—or at least not wrong.”

Psychologist Joseph Vandello has repeatedly demonstrated how culture influences perceptions of violence against women. One study (Vandello and Cohen, 2003) compared responses from Brazilian and American college students to two fictional scenarios involving a married couple. In one scenario, the wife is either a) faithful or b) having an affair that the neighbors know about. In the second scenario, the wife is unfaithful, and the husband either a) yells at her; b) yells at her, hits her across the face, and shakes her; c) does nothing; or d) demands a divorce. The researchers found that Brazilian students were more likely to look down on the husband because of his wife’s infidelity. They also found that while Americans rated the violent husband as less manly than the one who only yelled, Brazilians rated the violent husband as slightly more manly. These attitudes may help explain why, until 1991, Brazil allowed men to legally murder their wives in “legitimate defense of honor.”

Men are not the only ones who kill for honor. Pakistan’s most infamous honor murder involved a mother who hired a gunman to kill her daughter for leaving an abusive marriage. More recently, two Indian women strangled their daughters for marrying men of a different religion. “We killed them because they brought shame to our community,” one explained. These cases—along with the fact that men are also the victims of honor killings—challenge the assumption that women are victimized on the basis of gender alone.

There is a reason why North American feminists have worked so tirelessly to popularize the concept of “rape culture”: they understand that preventing violence against women depends on recognizing its cultural patterns (and yes—violence against women in the United States can be very cultural). Following this same principle, Ontario’s Punjabi Community Health Services offers family mediation services for conflicts driven by “dishonor.” Elsewhere in Canada, Dr. Mohammed Baobid is developing “culturally competent integration strategies” to help men coming from conflict zones curb domestic violence. Imagine if the Shafia sisters had access to resources like these. How could that possibly have been a bad thing?

(Photo Source)

Peter Gray recently finished his BA in Asian Studies at Clark University with a special focus on Indonesia. A Muslim convert, he writes about Islam, “Islamophobia” and interfaith dialogue at muslimerican.wordpress.com.

See Related Articles:

“Honor killings’ – What do we do now?” – By Abrar Qadir

“Violence: Honor killings and Islam: Is there a link?” By Omer Subhani

“Book: “Honour Killing: Stories of Men Who Killed”: A disturbing look into a killer’s psyche” – By Asma T. Uddin