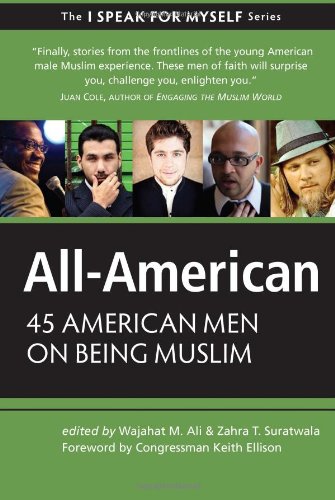

I opened All-American: 45 American Men on Being Muslim, the second publication in the recently unveiled I Speak For Myself series, fully expecting to roll my eyes at trite complaints about airport security or defensive rants against terrorism. Instead, I was quickly humbled by the realization that I, myself an ‘All-American Muslim man,’ was just as in need of an introduction to these 45 men as the presumably intended audience, non-Muslim Americans.

The book begins with a foreword and an introduction, from Congressman Keith Ellison and editor Wajahat Ali respectively, explaining the simple idea behind the book and the series – we cannot accomplish the Quranic command to get to “know one another” as human beings of a variety of colors and creeds without first opening our mouths or lifting our pens. Ellison and Ali also pose the question, to what extent are American and Muslim mutually exclusive identities? And with that directive and question in mind, 45 American Muslim men introduce themselves to us, or rather, to U.S.

The individual essays begin with a bang, as Haroon Moghul, a public intellectual, displays a raw honesty about the difficulties of Islam’s central command, to believe in God – how a totalitarian commitment to the “endless tasks assigned by Islam” left him “crumpled in otherworldly exhaustion, ” before he found himself able to accept Islam as a long term journey marked by balance. This vulnerability of belief makes for a fantastic humanizing introduction to the American Muslim man, who is often feared precisely because he is seen as impervious to any religious vacillation. The second essay introduces us to a white American Muslim, born and raised, Svend White, who cautions older generations to pick their battles when it comes to separating their Muslim children from certain elements of American culture. The wisdom of his advice is seen in the subsequent essays, as we discover so many Muslims to have created something positive, and very Muslim, out of American trends with no obvious Islamic nexus – such as baseball, hip-hop, and film.

The next 43 essays continue with succinct, efficient writing that manages to convey semi-biographical, intellectually and emotionally engaging prose without being any more rigorous a read than the sports section of the newspaper. A big reason for that being, perhaps, the abundance of sports analogies littered throughout the book! The American male experience cannot be properly conveyed without at least a steady stream of passing references to football and baseball, and we find that the All-American Muslim male experience is no different.

We are treated to the stories of converts who were finally able to shed their learned aversion to tears through their new religion , shaking up the understanding of masculinity they learned as young American men. We read first person accounts of the faith-based motivations behind our community’s most accomplished young civil rights activists. Reading about the isolation many Muslim men dealt with in settings I couldn’t fathom as a teenager coming of age in the Bay Area’s thriving Muslim community, I was reminded of the struggle of the sahaba even, the companions of the Prophet Muhammad, and their experience creating a new community in the midst of a mature, and often hostile nation.

As someone whose college foray into Hebrew was derided by many peers as disloyal to Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, I was delighted by all the essays which spoke of a fascination and camaraderie with the Jewish people. We even learn about Newt Gingrich’s surprising role in securing Friday prayer for Muslims on Capitol Hill.

All in all, the diversity of writers chosen was wonderful and not at all redundant. I don’t imagine the relatively high number of Bohra Muslims, an Ismaili Shia subset from the Indian subcontinent, chosen to contribute essay to this book was on accident, as they are a minority often seen as heretical by the larger Muslim population. I felt especially enlightened by Tynan Power’s essay on the transitions in faith that accompany transitions in gender, although D.C.’s openly gay Imam Daaiyee Abdullah’s essay may court more attention.

Though I have praised the diversity of voices given a chance to speak for themselves in this book, there were two omissions that need to be noted. One is that the writers came almost exclusively from the class of successful professionals. While it is beneficial to highlight for ourselves and the wider audience the professional contribution of Muslims to America, this book feels incomplete without the voice of someone like a taxi-driver or mini-mart owner, those who bear the brunt of the “go back where you came from” rhetoric this book is designed to combat – those without the privileges we over ascribe to white males, and under ascribe to successful professionals. In the same vein, every writer was either born in America or arrived at a very young age, and at least one essay from a naturalized American, a “masjid uncle” so to speak, could have been great for bridging the generational divide.

Minor critiques aside, All-American: 45 American Men on Being Muslim comes highly recommended, both as a gift for your non-Muslim neighbors and co-workers, and for your personal collection. Whether for inter-faith or intra-faith outreach, 45 American men have given us a blueprint for getting to know one another.

Abrar Qadir is a recent graduate from Georgetown University Law Center. Abrar maintains a regular blog at http://www.punjabirefill.com.