There was once a young four-year-old Moroccan girl named Rajae who lived in West Amsterdam. One day, she accompanied a Dutch friend to ballet classes and it was there she heard Chopin and Mozart for the first time.

It was a moment that changed her life.

“When I heard this music,” she tells me over Skype, “It was like a spiritual experience.” She intuitively knew she was destined for an artistic life.

Today, 29 years later, Rajae El Mouhandiz is a musician, a composer, an entertainer, and one of the few Muslim women in the world with her own record label.

On International Women’s Day 2013, Rajae launched a new era in her career with the short film, Hope, a new single, “Gracefully,” and further development of the International Museum of Women’s exhibition, MUSLIMA: Muslim Women’s Art and Voices, where she serves as co-curator. She is now about to record her third album. These are impressive achievements for any artist, but to really appreciate Rajae’s creative expression, one must understand her backstory.

In many ways, Rajae’s biography is similar to other North Africans in the Netherlands; her father, a tribal man from Admam, arrived as guest worker while his family remained behind. Rajae’s mother was his fourth marriage. A street smart woman with little formal education, she insisted that her husband bring the family to Holland to live with him. Rajae arrived as a baby to a cramped apartment and a father with scant Dutch language skills who was now burdened with a large family to support.

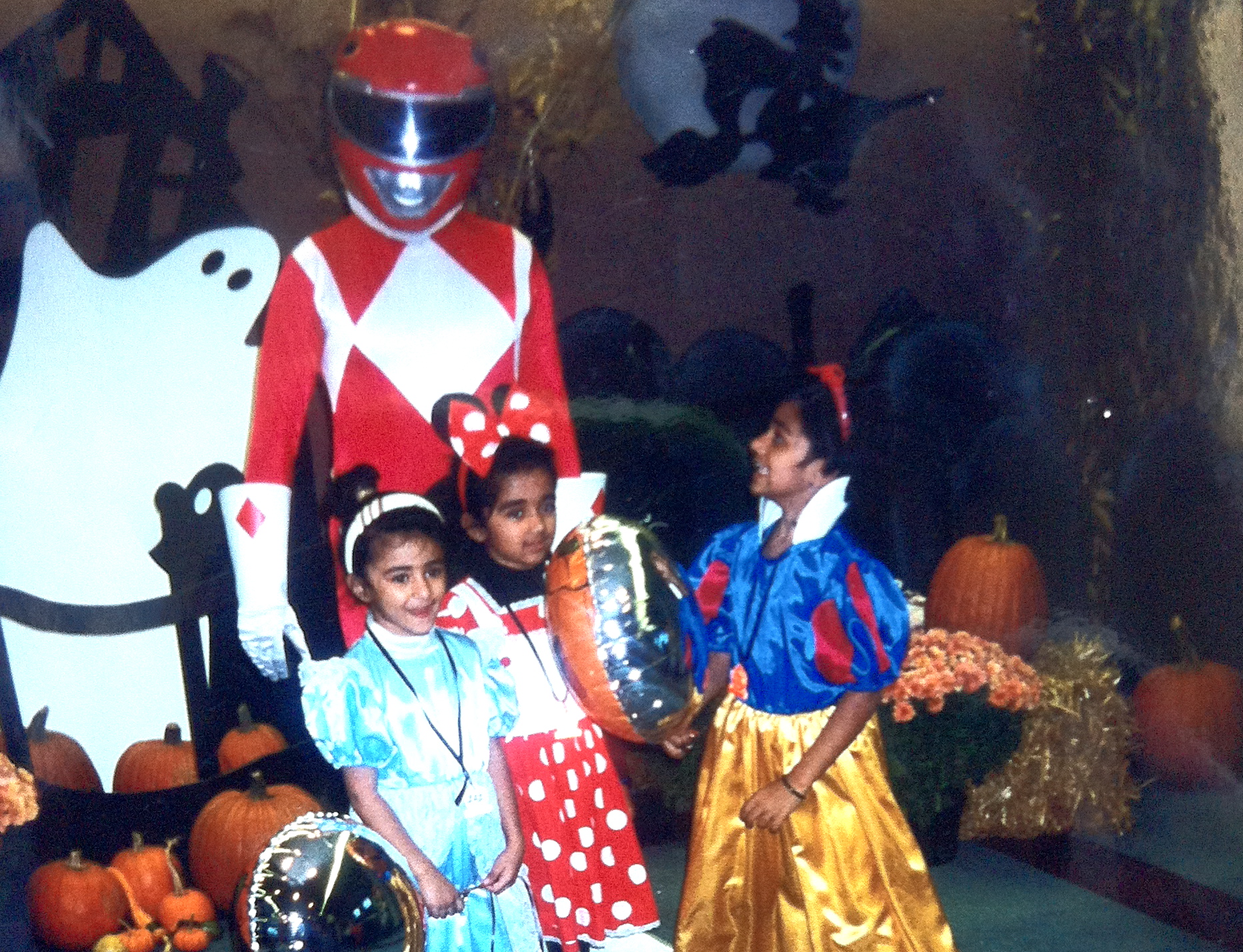

Here is where the story detours: family life quickly fell apart and within a few years, the police removed Rajae, her mother and siblings from the home and placed them in a shelter. Rajea’s fourth birthday passed unceremoniously in the narrow, austere room where the family slept. Eventually, they found a modest house in a neighborhood where they were one of the first Moroccan families. Although Rajea’s mother had siblings in Holland, they did not offer much in the way of assistance once she left her husband because “At that time, “Rajae explains, “there was little support from the Moroccan community for divorced women. The advice was to just go back to your husband.”

Her mother worked several jobs to provide for her children, but was a sickly woman whose exhausting work schedule often left her ill. In the absence of a father figure and extended family support system, Rajea’s brothers became insufferable as they entered puberty. The little girl found solace in her ballet classes and in learning the French horn. “I was different,” she recalls. “I liked being alone. I enjoyed practicing my instrument for hours, but my family didn’t understand me.”

Rajae’s Dutch mentors, however, did, but as she became increasingly integrated into her European country and culture through her music, her family began to resent her. After all, the Dutch were neighbors who Rajae’s mother depended on to help care for her children and now they had become Rajae’s peers and friends. Rajae was 15-years-old when her mother told her she had to give up music. The next day, the rebellious teenager ran. She had researched beforehand and knew the State would have to provide for her as an underage runaway and they did, temporarily relocating her to another city and assigning her a new name, which she kept for a year. As shocking and as shameful as her decision may have been for her family, “I finally felt free.” she says. “It was like a weight was lifted off of me.”

At 16-years-old, Rajae auditioned to attend classes at a music conservatory and was admitted as a fulltime student. She didn’t realize it, but at that time she was the first Muslim Holland had admitted into their conservatory system. Rajae was around an international student body of other creative personalities, and she finally felt at home.

She transitioned into an orchestra musician, but soon realized that she was becoming a secular, Dutch citizen. “I didn’t feel that the music I was playing connected me to my cultural or religious roots,” Rajae reveals. The ancestral and spiritual pull to her identity as a North African Muslim led the budding artist to jazz. This genre of music spoke to her pain and tumult; she quickly moved to writing and performing her own work. Rajae now has two albums under her belt, Incarnation (2006), and Hand of Fatima (2009) and is about to record her third.

These are no small accomplishments. Being an artist is a risky, lonely endeavor and Rajae’s gender only adds another layer of challenges. “Initially, many Muslim music labels wouldn’t work with me because I was a woman, and many non-Muslims wouldn’t back me because they perceived my identity as an investment risk.” The continent’s burgeoning xenophobia has made it difficult for Muslims to gain access to cultural space.

“Allah made the way clear,” she reminds me. In fact, she marvels at the magical twists in her life. One day, she had a strong urge to visit a particular bakery in a touristy area of town — an area she rarely frequented. She entered the shop to see her sister working behind the counter. This reunion ultimately led to a re-established connection with her mother, who asked Rajae’s forgiveness prior to embarking on the pilgrimage to Mecca. “If course I forgave her,” Rajae says. “It isn’t for me to get in between her relationship with God.”

These days more and more Muslims are morphing into cultural producers as writers, filmmakers, musicians, and visual artists. Commentators feel the next decade will cross a threshold: it may become culturally “cool” to be a Muslim. Rajae is one artist at the center of this forthcoming critical mass of coolness. In fact, this is the fifth year in a row that Rajae’s name appears as the only contemporary female Muslim singer in the World’s 500 Most Influential Muslims.

Yet, struggles remain. She finds that the number one hurdle young Muslim men and women interested in becoming an artist of some kind face is a lack of support from their families. “These things have no religious base. It is all cultural.” She believes that art addresses the soul of Islam and the beauty of Allah’s creation. She also laments that too many Muslims are money or fame-hungry in their motivations, failing to acknowledge the spiritual and cultural importance of art and creative expression.

Rajae’s work — her art, her music and her personal story– is a celebration of Muslim women as active participants in a global world. She doesn’t want her backstory misused to argue that Muslim women are victims. If anything, her life experiences stand as a testament to strength, and she remains connected to her family and her North African roots. Rajae also understands her role as someone who fosters connections between different communities. “Allah has been good to me. I don’t want people to see my pain,” she comments, “I want them to see my talent.”

A screening of her film Hope! Accompanied her recent performance in Amsterdam for International Women’s Day 2013. A screening took place in Denmark, as well. The response was phenomenal. “It was amazing…and humbling,” she writes to me afterwards. “People cried, a women wearing niqaab came to me afterwards and kissed, hugged me and thanked me! Men also reached out to me. Allah is so generous!”

She closes her message saying, “It is our time, sister.”

Deonna Kelli Sayed is an American-Muslim writer. She is the author of “Paranormal Obsession: America’s Fascination with Ghosts & Hauntings, Spooks & Spirits.” She also has an essay featured in “Love, Insh’Allah: The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women.” Visit www.deonnakellisayed.com to learn more.