A full moon hung low one North Carolina night. Omar ibn Said was on the run from his South Carolina master who had almost beaten him to death a month earlier. When Omar came upon a church, he whispered “Praise Allah” under his breath. He took ablutions by the well in the churchyard and then entered the sanctuary to perform his Islamic prayers.

A young white boy saw him walk inside. Men on horseback with a pack of dogs quickly arrived to snatch Omar, mid-prostration, off to jail.

He was arrested not only because he was a runaway slave or because he was a Muslim, but also because he was a black man praying in the wrong place.

He was a runaway slave in North Carolina, but in Senegal, Omar had been respected Islamic scholar and fluent in Arabic. He entered a church to pray because he knew it to be permissible based on his knowledge of Islam. The Big Story of American race and slavery insisted that it wasn’t.

There are parallels to Omar’s story and that of Muslims in contemporary societies: our prayer spaces are contested, our internal and external politics remain raced and sectarian, and we are sometimes inadvertently in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Years later, Omar would scribe his personal story and submit the first American-Muslim narrative in Arabic. He would write fourteen Arabic manuscripts, perhaps becoming the most prolific early American-Muslim writer, but Omar, who died in 1867, would remain a slave and a scholar for the rest of his life. According to many researchers, he is one of the earliest narrators of an emerging Muslim identity outside of the traditional Muslim world, and one fraught with contradictions and compromise.

In his autobiography, Omar reveals:

I cannot write my life because I have forgotten much of my own language as well as of the Arabic. Do not be hard upon me, my brother. — To God let many thanks be paid for his great mercy and goodness.

Omar could not have envisioned that almost one hundred and fifty years later, there would be emerging global interest in Muslim stories, and the ability to tell these stories would remain politicized and problematic.

Recently, a Muslim woman who occasionally speaks publicly on Muslim issues, privately expressed to me frustration in never being able to move beyond the Big Story – be it from non-Muslims or fellow Muslims who insist that there is one truth about the Islamic experience. “I get so tired of always having to talk about the same things,” she said. “We never seem to get the good stuff.” The Big Story deems Muslim men seemingly harsh and women silent. That same story often views Islam and the Muslim world as a place of dysfunction.

There is an emerging mass of Muslim women who are no longer talking back to the Big Story but speaking forward to a new one. An emerging group of Muslim cultural creatives — filmmakers, visual artists, musicians, and writers – are unapologetically exploring how to tell diverse stories of faith and identity. Writer Kamran Pasha invited Muslims to embrace the arts as storytelling in 2009, and today we are beginning to see an influx of Muslims doing just that.

The success of various projects such as online magazines like Altmuslimah.com and LoveInshallah.com, the artistic voices featured at The International Museum of Women Muslimah Exhibition, and the forthcoming Muslimah Montage, which showcases vibrant American-Muslim personalities dedicated to promoting multiple stories of the Muslim experience from a female (and sometimes male) perspective.

Storytelling also offers transformative ways to speak with our community on uncomfortable issues like sexuality, gender, spiritual struggles, and controversial personal decisions (such as abortion, for example). Dutch-North African musician and artist Rajae El Mouhandiz is focusing her forthcoming TEDx talk on telling new stories through art and hybrid immigrant identity. Hind Makki’s Side Entrance project tackles gendered spatial politics in American mosques to contest the Big Story. Meanwhile, the documentary Unmosqued explores how the Big Story is potentially alienating a growing number of Muslims searching for an authentic spiritual connection within traditional Islamic institutions.

Muslims desire to exist beyond the political narratives that often enslave us to outdated, inaccurate stereotypes. The only way out is create a new language through creative expressions. These stories won’t come from the minbar. They will emerge from the Muslim street, a reality already acknowledged by Chicago’s Inner-City Muslim Action Network which organizes the increasingly popular summer Muslim arts festival, appropriately called “Takin’ It To the Streets.”

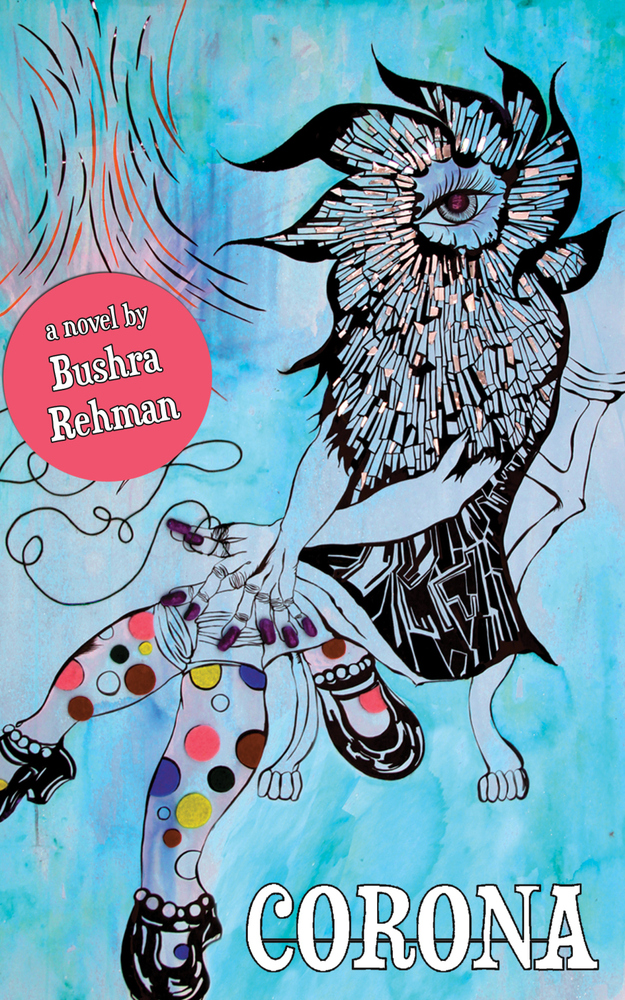

Bushra Rehman, the author of Corona – Not the Beer But the Place in Queens, shared in an interview that owing your story is hard work. She accepts that other people sometimes act as if “they have more ownership over your story than you do.” Ownership may be the most challenging part of the storytelling, particularly when many Muslim communities insist certain topics are shameful for public discussion, such as stories about love or personal faith struggles. Ownership requires letting go of community and mainstream approval and believing that an audience is out there who will connect with your truth.

My own story is a good example. I am what most call a convert/revert to Islam. I have been Muslim for almost two decades and I have always found the convert/revert label to be unsophisticated. The debates around this discussion are not new but they remain attached to the Big Story, as if my identity is defined by what I am no longer (a mainstream Christian) to what I will never be (someone with roots to a Muslim-majority culture). I wanted to reorient my faith post-divorce but felt my struggles were unique to a white female convert and assumed few readers would relate to the road I was traveling. Nevertheless, I started writing about my vulnerabilities and discovered many different types of Muslim women (and others) connected with my personal journey. I did not realize that anyone was paying attention to my work until Loveinshallah.com asked me to join as an editor.

In the context of Muslims in Europe and the United States, we are all forming new identities and stories regardless of our birth culture. We are all converting, and ultimately subverting, the Big Story of our faith and respective birth cultures. Islam, since its earliest days, has consistently turning inside out paradigms around race, faith, and cultural identity. Omar ibn Said is one homegrown, historical example with more emerging from contemporary Muslim storytellers.

I feel an affinity for Omar ibn Said as he showcased intellectual and cultural resistance by writing his autobiography. When he copied by memory Surat an Nasr, there were mistakes as his “memory failed him.” These omissions are somewhat reassuring. Despite our Islamic knowledge being incomplete, our faith-based stories are authentic and powerful.

Today, Omar’s Arabic Bible, with his own Islamic inscriptions in the margins, sits in the Davidson College Library in North Carolina. A picture of Omar’s Bible is featured in the Muslim Self Portrait exhibition, a project launched by North Carolina photographer, Todd Drake, where Muslims use photography to tell personal stories. The book sits tenderly wrapped the same way many Muslims protect their personal Qur’an. The fabric is pieced together with raw and untidy stitches, but there is love and care in the presentation. We honor Omar’s legacy when we open up and tell our own truths.

Deonna is a writer and multimedia artist who blogs on her personal site and at Love, InshAllah: The Secret Loves Lives of American Muslim Women.