The winter of 2013 was an eventful one for me. As a second-year medical student from Pakistan, I spent two months at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore for a research elective-. It was a time of excitement, wonder and anxiety. One afternoon, after hurrying back to the office from lunch, I stood fidgeting with the office key, struggling to open the door. A middle-aged lady impeccably dressed in crisp dress pants and a blazer, who I had bumped into and exchanged pleasantries with the day before, kindly offered to help.

After she and I had managed to unlock the door, she turned to me, a bit hesitantly, and said, “So listen, I have been meaning to ask you….why do you cover your head?” I was, in all honestly, taken aback, but I noticed that her tone was neither condescending nor pitying. Instead it was laced with curiosity. And that made all the difference.

My answer was simple. I explained that my headscarf was a piece of my religion and my religion was, in turn, my identity. I added that I had chosen to don the headscarf; my decision had not been influenced by culture or family. I kept my answer brief as I had to return to work, but she seemed satisfied with the few details I did offer and smiled in response, saying she thought the hijab was a beautiful concept.

What struck me most about this exchange was not the information I had been able to give this woman, but the voice she had given me. When she noticed that I did something she had seen few people do in her homeland, she approached me and asked. She simply asked. She did not assume or infer or assign labels. She allowed me to speak for myself and listened with an open, compassionate mind to my narrative over whatever pre-conceived notions she may have held or whatever convenient caricature society had constructed of Muslim women like myself.

I didn’t see this woman again, but she left an indelible mark on me and how I approach people. Now I listen to people. Listen to why some women—Muslim, Jewish or otherwise–cover their heads. Listen to why others don’t. Listen to why some youth are devoted to their religion. Listen to why others are not. Listen to why some seem to be enjoying their lives to the fullest. Listen to why others are not.

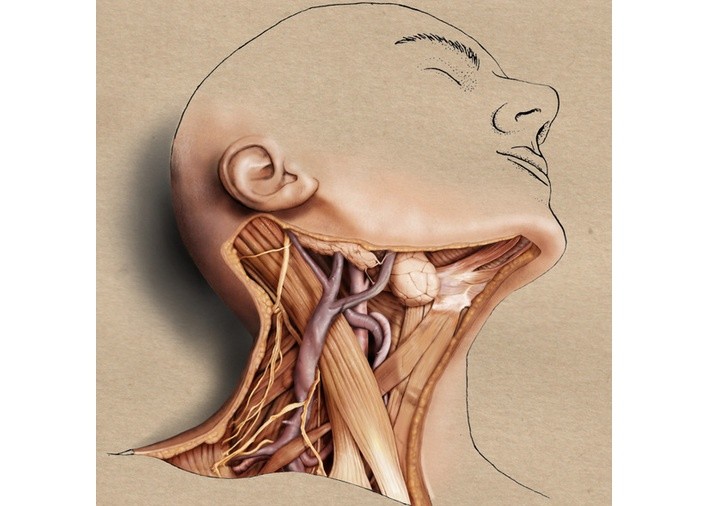

In the chapter 55 of the Qur’an, titled Surah Ar-Rahman, Allah reminds His creation how He gave human beings the ability to speak– in other words, the gift of communication. Physically speaking, our vocal cords are marvelous sight to behold. As a medical student, I once had the opportunity to observe an anesthesiologist as she intubated a patient. Once the patient had been sedated, she snaked a tube down his throat and into the windpipe. As the anesthetist slid in the laryngoscope, a camera-like instrument that allows us to see inside the windpipe, I stood right beside her and peered down at the small, white glistening cords that enable us to speak.

Sitting smack in the middle of the pink, wet, bloody tissue that makes up our throats, these miniscule cords stood out like pearls. They are so puny you would hardly think they were created for a purpose at all, but when their edges vibrate in the airstream, they produce sound. Sound that allows us to learn about one another. These cords sit at the base of the throat of a tyrant as he spews out hate. They sit in the throat of the victim as he cries for mercy. The sit in the throat of the one who tries to explain herself.

Their physical frailly and delicateness is surpassed only by the beauty of their purpose. When we misuse them, it results in broken relationships, broken communities and even broken nations. But if we use these pearls to give the “other” a voice, we build, and even mend, human connections.

[separator type=”thin”]

Butool Hisam is a medical student from Pakistan. I blog at: http://nurturingfaith92.tumblr.com/ and http://labyrinthine916.blogspot.com/. I also write for The Express Tribune Magazine http://tribune.com.pk/author/4399/butool-hisam/.

(Artwork credit: Catherine Sulzmann)