altM’s Founder, Editor-in-Chief, and religious liberties lawyer Asma Uddin reviews the Marrakesh Declaration, and what it means for religious freedom.

In the 13th century, when the Mongols conquered Baghdad, their ruler Hulagu Khan gathered the religious scholars in the city and asked them: According to spiritual law, which option is preferable: a disbelieving, but just, ruler, or a Muslim ruler who is unjust? After some reflection, the scholars chose a disbelieving, but just, ruler.

This focus on righteousness in Islamic thought as the privileging factor seems to be lost on today’s extremist actors. Instead, militants vie for power and control, and seek to obliterate peaceful—or righteous—believers of both their own and other faiths. As a result, religious minorities in Muslim countries are increasingly under strain.

But some prominent Muslims are trying to fix that. At a convention led by Sheikh Abdullah bin Bayyah, a Mauritanian professor of Islamic studies at the King Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, more than 200 Muslim spiritual leaders, along with guests of other faiths, gathered in Marrakesh, Morocco in January. Their goal was to discuss the protection of these minorities.

The backdrop to the discussions was the Medina Charter, drafted by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) 1,400 years ago, as a blueprint for peace and cooperation among diverse religious groups. The conference, conveners felt, was called to action by what has now become a frequently recurring tragedy of death and destruction by Muslim extremists.

And well they might. Last month, on Easter Sunday, many of the Christian families of Lahore in Pakistan were celebrating their holiday with a picnic in Gulshan Iqbal Park. It was a crisp, sunny day and the kids were eager to enjoy the rides and frolic in the playground.

But their mirth was interrupted in the most tragic of ways. A bomb blast tore through the park, killing scores of women and children. The Pakistani Taliban had intentionally targeted Christians, who make up only 2 percent of the country’s population.

This wasn’t the first time—and most likely won’t be the last—that religious minorities in Pakistan have come under attack. Last October, a suicide bomber attacked a Shiite procession in southern Pakistan, killing dozens and wounding many others. That attack followed a string of others targeting the country’s Shiite community. The nation’s Ahmadi community is also under attack, with some saying that persecution is very nearly condoned by the law.

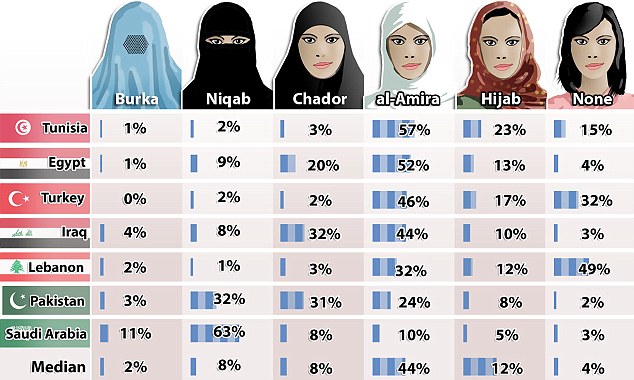

While Pakistan may be especially egregious in its religious freedom violations, it is certainly not alone among Muslim-majority countries when it comes to curtailing (with force, if necessary) peaceful religious expression. Egypt and Indonesia, among others, have blasphemy laws on the books; and small sects, such as the Ahmadis in Indonesia and Quranists in Egypt, face persecution in their countries.

But the Marrakesh conference is a strong sign of change to come. The Marrakesh Declaration—issued at the conclusion of the summit—states that the Medina Charter lays out a framework for the protection of religious minorities in Muslim-controlled states, and those principles must be applied today.

“…The Charter of Medina[‘s] …provisions contained a number of the principles of constitutional contractual citizenship, such as freedom of movement, property ownership, mutual solidarity and defense, as well as principles of justice and equality before the law,” according to the declaration.

It goes on to say that “The objectives of the Charter of Medina provide a suitable framework for national constitutions in countries with Muslim majorities; and the United Nations Charter and related documents, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, are in harmony with the Charter of Medina, including consideration for public order.” It does however, fail to take on the task of protecting those of no faith, an increasing number of whom reside and live in Muslim nations.

In the face of recurring violence against minorities in Muslim-majority states, the declaration seems to be facing an impossible task. Even the conference convener, bin Bayyah, mused out loud that “We are heading towards annihilation.” So it is not surprising that many have responded to the declaration with, at best, skepticism and, at worst, cynicism.

Shadi Hamid of the Washington, D.C.-based Brookings Institution told the New York Times that the declaration is useless because it fails to target “people who are predisposed to radicalism. A young Muslim who is intrigued by [Daesh] would be more likely to listen to a Salafi scholar than a traditionalist scholar.”

Beyond criticism of methodology, Muslim and non-Muslim groups, concerned about religious liberty, are demanding concrete action. They worry the declaration follows in the steps of other feel-good but ineffectual initiatives, such as the 2007 “A Common Word” statement that called for interfaith engagement. That document was signed by 138 Muslim scholars and endorsed by dozens more. Its on-the-ground impact? Not much.

Read more here.

Photo credits here.

1 Comment