For anyone who has experienced one too many setbacks in search of love, the question “Where am I going wrong?” is a familiar one. And if you have asked this out loud, you will find no shortage of opinions that scrutinize your character or the foibles of your long-gone suitors. The trouble with this question is that it invites you to view parts of your journey as either right or wrong. This rush towards a binary understanding obscures from uncovering constellations and building presence that is necessary to change the course of your life.

I know this all too well. I have often reflected on why it took me six long, and difficult, years before I was to meet my spouse. Now, in my late twenties, I have come to realize that I was not as conciliatory as I perhaps ought to have been towards men I considered outliers, but who were in fact pointing me in an altogether different direction to the one I was indignantly pursuing.

The more I conceived of life in binaries, the more it began to spin out of my control. And while I did ‘let go and let God’, it often felt like there was no plan, only chaos. I could unearth no patterns in my encounters and could not see what I was meant to take from them except a deep sense of disappointment. All of this changed when I began to reflect on outliers.

What is an outlier, you ask.

An outlier will typically diverge in a big way from the general patterns that may govern an event or scenario. They will not sit neatly along a correlation so we have a tendency to ignore them, or worse, reject them as spurious. While our normative patterns in life may be skewed in a given direction, the presence of these seemingly random and deviating outliers is reason to pause, reflect and learn. Especially since they may hold the key to denouement and divinely guided discernment that we all long for in moments of doubt.

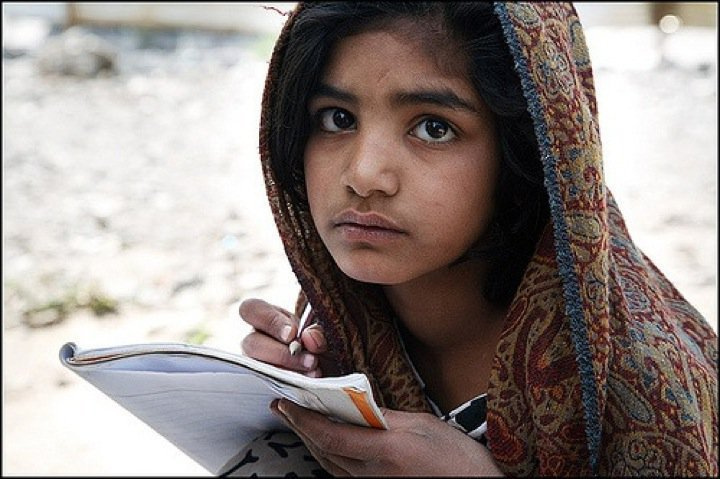

My usual pattern of distribution consisted of Muslim men born into the faith, often belonging to the South Asian heritage. Now, before you assume that my bias had anything to do with a deep seated prejudice, allow me to elaborate. Belonging to a niche ethnic group, even by Asian standards, many of my family members settled by chance or providence with non-Asians, and although these unions carried a burden of cultural misunderstandings, I knew full well that the reverse – that is marrying someone within the Asian community – would carry its own set of cultural misgivings. My biryani making skills were faultless but there were other, more serious, parameters that made me rather unconventional, even a pariah, among this demographic. In any other setting these eccentricities might have been accepted, perhaps even celebrated, but on the marriage circuit they invited harsh scrutiny. Whether it was in person or online, judgments would come in thick and fast.

I was too strong, an over-thinker, an overachiever, and generally quite eclectic.

‘Nowhere and everywhere on the map,’ someone once quipped.

Many of the men I met along the way were simply looking to fashion a woman into their life. A great deal of dogma would get expressed about the role of women, whether that was as a housewife or a career woman. Whatever the preference, you could be sure you would be living according to someone else’s script. An equally significant number of men were disturbingly uncomfortable with ‘love’ and expressed a kind of denial and juvenility characteristic of someone altogether disassociated from their self.

Some would tell me flatly that they did not expect to feel any love before marriage preferring a more formal setup with a probing that was second only to a job interview.

Others expected much too much, not by way of love, but lust.

There was much pretense, too little substance, and far too many misplaced sensibilities. Naturally, in my early twenties, I found myself under immense pressure to ‘change’ and configure myself to placate these sensibilities, the consequence of which was a deep sense of unhappiness and feeling both misunderstood and out of synch with my own community. A community I felt, and still feel, has much too little appreciation for a woman with character, convictions or of strong mind.

Not everyone was drab, however. There were some charming, intelligent and successful Muslim men who I developed a regard for. But for one reason or another – most commonly challenges meted out by their families and a lack of agency these men would feel as a consequence of familial pressure – these would fizzle into nothingness. These liaisons – as many as twenty or more – would all lead nowhere despite my best efforts. The prevailing pattern that kept on emerging was one centered on family dynamics. Many men were unable, or reticent, to swim against familial expectations and dogma. Some would openly admit to the restraints imposed on them by their family. Others offered much less by way of honesty but their vacillating emotions belied the dilemma they felt. Even where there was an inclination to swim against the current, I had to be prepared to negotiate all granularities. Every choice, from what I wore to my behavior, was under the microscope. All of this was in stark contrast to my life where complete, unfettered freedom prevails.

As you might expect, with each successive encounter, I found it difficult to get back up again. Once, twice, thrice would have been tolerable, even expected. But the enormous pile of potentials that had bottomed out left me at the mercy of one too many a dinner joke. The uhm’s, ah’s and tut’s left me so deflated that I eventually settled on the idea of spending my life alone, the upside of which was that I could travel and pursue any direction owing to a lack of commitments. It was not an altogether bad trade-off, I would tell myself.

Looking back, I realize I had not heeded any of the signs that had manifested very clearly before me. While I searched my own community for unconditional acceptance, the men who did in fact fall very easily in love with me were a world away from this community. They would almost always be European and – to my surprise – also non-Muslim. The great irony was that they could see past my hijab and adherence to my faith, while a great number of Muslim men would show disdain for head coverings or split hairs with me over the finer points of fiqh. I would often wonder what I was meant to take from it all.

There were three outliers that I had brushed off as insignificant at the time, but my encounters with them were ones that I ought to have reflected on, if only to stop myself replicating negative cycles again, and again, with the Muslim men I was considering for marriage. There were lessons, character preferences, and criterion locked up in these encounters that I could have learned from, if only I had allowed myself to be present in those moments.

The first outlier was a complete stranger, a foreign student I met in a coffee shop, who ended our first chat over the latest issue of the Economist with “we should do coffee sometime.”

People say that all the time, don’t they? Thinking nothing of it, I did not expect to hear from him. Except that I did. His devotion to Christian values anchored him towards humanitarianism, a family orientated attitude and a comprehensive scriptural reasoning that made his outlook similar to my own. We were alike in many ways, passionate about the same things and both in want of a partner who was motivated by universal principles. I saw a reflection of myself in someone I did not expect to. The rapport was not one I had found elsewhere. Still, I dismissed it as an exceptional experience and it fizzled out when we both realized that our desire to be with someone from our particular faith tradition was an obstacle to continuing any further. But what came next plunged me into greater self-doubt.

On a backpacking trip in a neighboring country, I found myself stuck one late evening in a strange unknown place. All trains out of the town were cancelled with normal service resuming the next morning. As I stood deliberating with myself about what I ought to do next, he walked up towards me and asked me if I needed help. We would eventually carpool together with two other stranded passengers.

Effortlessly charming and chivalrous, he was unfazed by distances and for months to follow he was in pursuit of getting to know me better. The experience left me deeply upset.

I realized that there were certain qualities I could not possibly compromise on when it came to finding a spouse – qualities like kindness, initiative, protectiveness, and old school chivalry—and while this man possessed those very characteristics, so many of my more conventional suitors did not.

Soon after, yet another outlier came along. A militant atheist with a penchant for mocking believers of every variety, he was someone who never missed an opportunity to express his revulsion for theism, and Islam, when we socialized. After getting into a wrangle one too many times, I settled on smiling through his attempts to provoke me. I would often catch him staring at me, but made nothing of it. I figured he was simply looking to finesse his next put-down, of which he was never short. I resigned to ignoring his inflamed rhetoric in the interest of friendship. Then, one day, he expressed his feelings for me, leaving me speechless. Suddenly I realized why what I said – and believed – mattered a great deal to him. Our differences melted away, replaced by a respect that has remained since. The experience taught me to strip back external layers – the masks, rhetoric, and modalities that people adopt to cloak their inner self. And to give the benefit of the doubt.

As I look back, with the benefit of hindsight, I see a reflection of myself in these outliers, their persona, and their interests. The most obvious lesson I have taken from these encounters is to never assume or second guess intentions.

Too often I would assume that on account of obvious differences in faith they would simply not be interested or unable to understand my character and motivations.

But these concerns were all untrue and skirted over the nuances I discovered when I took a closer look. These were not fetishized kinds of encounters with ‘the other’. Quite the contrary. My conversations would flow naturally with them and I found a safe space to express myself, one that was surprisingly not replete with judgements. I found a willing ear in them, and a great deal of understanding towards the common experiences and challenges that define the human condition.

Some years on, I feel I have gained perspective. I now realize that love can – and does – grow in the most unexpected of places and, if by Divine providence it has come your way from an unexpected direction, you must see it through to the end with an open, receiving heart. I have also come to understand that this does not mean you need to compromise on your beliefs. Only that it – whatever it may be – is destined for you however challenging and testing it may be. Acceptance of what Allah (swt) sends to you, and recognizing that it is intended for you, is part and parcel of tawakkul. My search was to end with an outlier, albeit one who had found Islam. Only then did I fully understand how life happens when we are busy making other plans. And how it is in the tangles of existence, when our objectives are unmet, that we learn a great deal about who we are and why things unfold in the way they do.

My young self would not let in anyone who did not meet my exacting standards and, as a consequence, I was not present in the experiences that were unfolding before me.

The alchemy of presence was not something I had much appreciation for as a young singleton. And so I found myself unable to take control of my journey, reinforcing a sense of helplessness. Building presence can be incredibly difficult in the thick fog of intersectional exchanges. We often do not have the distance to be able to examine ourselves, the other, or the situation. And yet every one of us most certainly has an outlier, an individual who does not neatly fit our criterion or usual modality on some front. My own experience has taught me that the discernment locked up in these outliers can enrich your perspective in ways you may not anticipate, and point you towards your manifest destiny.

R. Khan is a freelance writer based in Europe.

Nice Article

sure it’s really very nice article.