When I was asked to sit down and write my thoughts on Muslim Masculinity, I hit a wall. The reason for this is mostly a function of my present situation. I’ve been in a successful marriage for the last five years of my life while raising two children as a stay-at-home dad. I also live in an intentional community in rural Virginia isolated from a large Muslim community. The nearest major city is three hours away. To be clear, I haven’t had to think in terms of my own masculinity in a number of years, but here is my attempt at unpacking it.

I had just become a teenager when the internet was first made available to the public. My brother promptly got us online with one of those floppy disks promising hours of free America On-line (AOL) internet. After my initial fear of chatting with strangers, I began to make several online connections. Unfortunately, I had a scary experience early on after meeting a woman who actually turned out to be a male online predator.

After that experience, I took a step back and thought in my fourteen year old head:

“What person could I chat with online that no one would want to pretend to be?”

The first people that came to mind were Muslim women. From that point on I exclusively searched for Muslim women on AOL and messaged every single one and introduced myself. As a victim of physical bullying at the hands of hyper masculine classmates in a predominantly White, upper-middle class school, I perhaps found a safe place and empathetic ear among Muslim women.

What ended up happening instead was that they began to share their experiences with me, requiring me to listen and pay close attention to the complex and full lives of these women.

I believe that the practice of listening and reflecting on the stories of Muslim women informed my ethics today and the way in which I experience masculinity in my relationships and my marriage.

Growing up, I had the benefit of a family where gender roles were not necessarily fixed. Sure, my mother and father had their usual responsibilities but there was some flexibility, especially as they aged. If my mother was tired, my dad would vacuum. If my dad was tired, my mom would mow the lawn. Despite my dad being the main source of income, both my mom and dad spoke about money as a shared resource. As my mom would explain often, whatever needed to get done got done no matter who did it. While my older brother didn’t have this experience, I remember my father regularly sitting down with me and whipping out a copy of Reader’s Digest and inviting me to talk, “”Let’s talk about love, Beta.” He would share his take on the relationship-related anecdotes within the magazine. In the meantime, my sister introduced me to the poetry of Taslima Nasrin while I was still in middle school, shared books by prominent Muslim feminists in my early teens, and even handed me a copy of an academic article on how rape victims in Pakistan were charged with zina as a result of a screwed up interpretation of Islamic Law.

While my home was a safe space, my school was very much a rough environment characterized by bullying carried out by hyper-masculine young men. The young men sought to exert physical dominance over the other, and preyed on those who they perceived as weaker than themselves in lieu of any real communication. To choose just one example, in homeroom I asked a football player whose arm was in a sling if he was okay. He seemed to have construed this as affront to his strength and had me pinned against a desk within a matter of moments, angrily berating me for not minding my own business.

Just as I found a virtual community of Muslim women after running into an online predator, I was able to emerge from the hostile school environment and into a safe space cultivated by a group of women at my university. I am indebted to the group that welcomed me on a trip to attend the World March of Women in Washington, DC. While at university, I was able to continue reading feminist literature while pursuing a concentration in Women’s Studies, as well as in practice continuing to engage with a community of Muslim women at Smith College. After leaving the wonderful communities I encountered at university, I struggled with the heavily gendered expectations in the world of relationships, although I don’t claim to have suffered any real difficulties in comparison with the pressures women have to face in that sphere. A failed engagement featured many of the same themes I had encountered before, in which my then-fiancee and her family were put off by my interests and life choices. In particular it was thought of as odd that I would have preferences regarding my wedding outfit, and most crucially they viewed my ideal of a marriage featuring financial and domestic equality as unreasonable.

Eventually, I ended up marrying a woman who defies a rigid idea of femininity just as I defy a rigid idea of masculinity. She accepted me as I was, a man with varied interests who had always felt comfortable around women and a man who ultimately realized that the role that appealed to him the most was that of a stay-at-home dad.

This entails a good deal of work, with two kids to take to school, regular cleaning of the home, and also time for serious activities such as growing vegetables and keeping bees for honey.

I end up maintaining more social connections with our friends and community day-to-day as my wife works full time, and often has to travel out of town on business. One can look at this skeptically as an attempt to simply reverse the traditional spousal gender-roles, but the way that we make this work in practice is through a marriage contract that we mutually agreed to, based on a template produced by Naeem Jeenah. In addition to allowing us to set our own individual social and financial boundaries and responsibilities, our contract clearly states that we agree to share domestic responsibilities and that “it will not be the sole duty of either spouse to maintain an attractive domestic environment or to provide meals and, in general, to maintain the household.” Preserving a mutual, co-operative decision making process is at the core of our household, and this is the way we are able to make our marriage “work” while transcending the force of traditional gender roles.

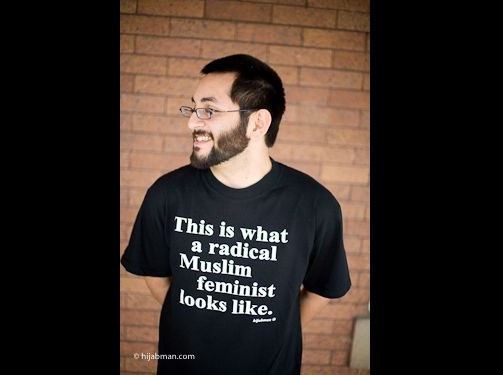

Javed Memon (aka “Hijabman”) will be presenting at the Muslim Masculinity in An Age of Feminism Conference: