It all happened after a Muslim woman threatened to sue the police department when they forcibly removed her hijab during her arrest.

There’s a police officer in the room with me, and he’s shouting “You don’t know what you’re talking about, ma’am!”

I tremble inwardly, but I don’t back down.

In fact, I tell him: “I must ask you to sit in your seat, officer, and listen carefully to what I’m saying.”

Yes, this really happened, and no, I wasn’t getting arrested. In fact I was training him and about a hundred other officers on cultural sensitivity.

It all started when I got a phone call from a police officer in the Houston Police Department (HPD) one morning in 2011. He was an instructor at the police academy and he wanted to know if I would be willing to participate in a training program he was designing. It was a series of presentations by community leaders of minority groups, and they wanted me to present on Islam.

He told me he’d been referred by someone who had been to some of my interfaith events. I am vocal in the Houston area for my interfaith programs and I frequently write for websites and newspapers about issues pertaining to Muslims.

While I wasn’t a celebrity, I would often meet strangers in the mall who told me they’d come to one of my events. But this police training was to become a turning point for me in many ways, in the reach and exposure of my work and so much more.

This was before the videos of police brutality became common, before the #BlackLivesMatter. I wondered why was the HPD wanted to train officers on cultural sensitivity now.

The last diversity training had been years ago and since then the demographics of Houston had shifted tremendously. We’re now the fourth largest city in the nation, with a population growth of 5% between 2010 and 2013. Approximately 72% of Houstonians are native born (statistics from the City of Houston website).

Bottom line: The police department realized that officers had to know how all residents think and feel and practice, not just a small minority.

The final piece of the puzzle fit later. I learned as the months went on that a Muslim woman had threatened to sue the police department after they had forcibly removed her hijab during her arrest.

As a proactive step, the HPD wanted to train their officers on dos and don’ts about Muslims, as well as African Americans, Hispanics, Asians and other minority groups.

I agreed to the training, because it sounded really interesting and valuable. We had a grueling schedule of three weeks out of the month, every month, for a full year.

Yes, it was that long and intensive because the HPD wanted every officer with at least one year of experience on the force to go through this training. That meant all officers at every level, including the chief of police.

Over the next few weeks, I created my training materials, assembled my team (I needed a couple of other people to take over the classes when I wasn’t able to attend) and got ready to train more than 5,000 police officers.

I had been told that I couldn’t teach about religion itself but about the cultural aspects of it: What a police officer could expect when he entered a Muslim home, stereotypes about Muslims, why we do certain things and don’t do others.

I still remember my first session. I was shaking in my shoes, and my note cards were trembling because I couldn’t keep my hands still.

It was a huge auditorium with about a hundred officers in uniform. I probably didn’t sound too confident or knowledgeable, as adrenaline rushed to my head.

As time went on, the nervousness eased, and this year-long experience helped me develop my public speaking skills like nothing else could have.

I probably taught my students a lot, but I also learned an immense amount.

True, there were students like the police officer I mentioned earlier: rude, obstinate, convinced of the ugly lies Fox News was feeding them. But there were countless officers who listened carefully, made notes, and asked questions.

They wanted to do a better job in dealing with the rapidly growing Muslim population in Houston (the largest in Texas by some accounts) and that gladdened my heart to no end. I wanted to make my city a more open place to live, somewhere I could wear my hijab without dirty glances or snide remarks. This was just one small step toward achieving that goal.

I also learned that Houstonians — and possibly all Americans — have an immense curiosity about Muslims and Islam.

At the start of each session, when I would introduce myself as a Pakistani American, born and bred in Pakistan, I was frequently asked probing questions about my life there.

Most queries started with “I have heard…” or “is it true…?” The media presents very stereotypical images of Muslims, and doesn’t do a great job of portraying everyday Muslims doing ordinary average things.

Americans often don’t know much about people living in the Middle East or Asia, the majority of the Muslim world.

Often they don’t even know how their own American Muslim neighbors live, the Islamophobia we face every day and the ways we live and love American life.

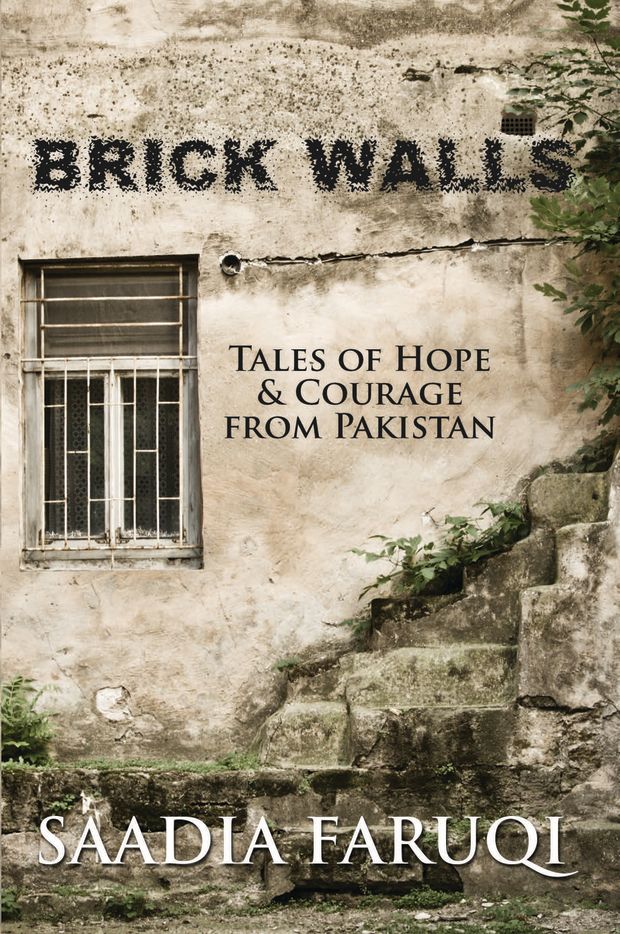

After my police training ended, and things became less hectic, I sat down to write. This time, instead of an op-ed or an academic paper, I turned to fiction. And so my short story collection Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan was born.

Thanks to the training sessions, I realized that there are issues I am well-positioned to address, questions I am well-equipped to answer.

I can share my experiences, I can allow my stories to portray a culture and people the way they deserve to be portrayed: truthfully.

My book is full of anguish and misery and pain. But it’s also full of hope and help and courageous people who struggle regardless of circumstance.

It’s my way of showing Americans what the media isn’t telling them: Muslims are just ordinary human beings, with emotions and fears and weaknesses like them.

Saadia Faruqi is the author of Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage. This piece was previously published at xojane.com.

Thank you for hope