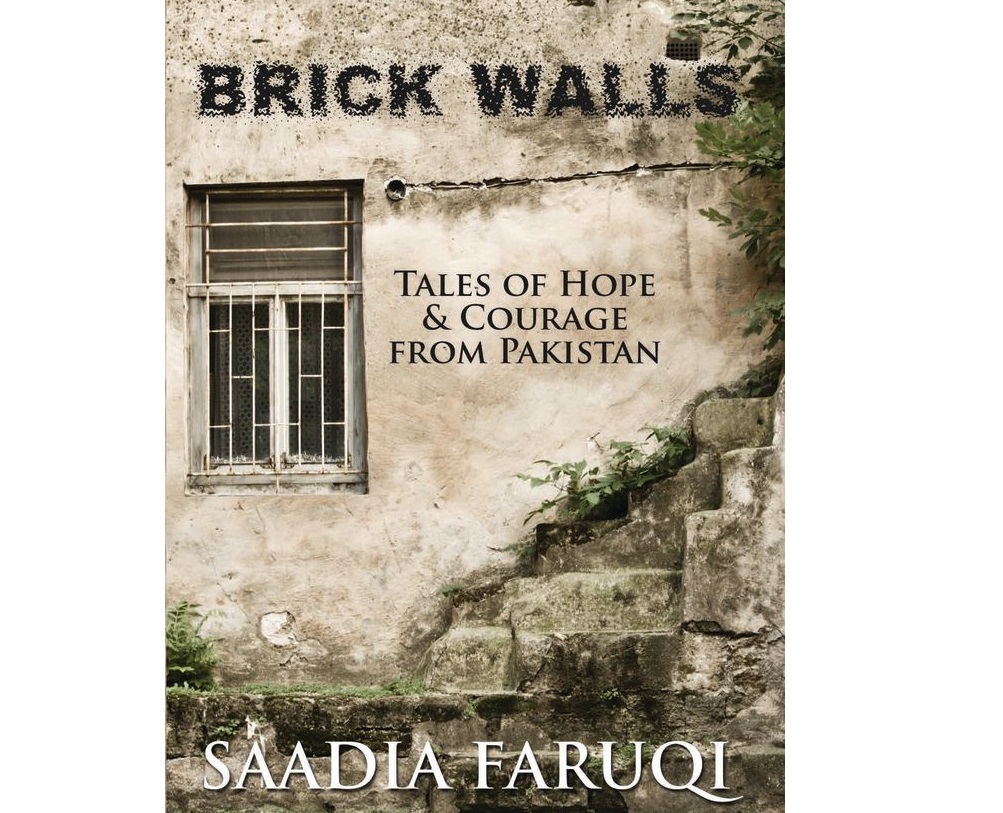

altMuslimah recently spoke to Saadia Faruqi about her debut work of fiction, a collection of short stories titled “Brick Walls: Tales of Hope and Courage from Pakistan.” An excerpt from the book follows the interview.

What is “Brick Walls,” and what is it not?

“Brick Walls” is a portrait of Pakistani life, a series of snapshots taken from different angles. This book takes a hard look at the obstacles facing ordinary Pakistani people, and showcases the both the beauty and ugliness of that culture. What “Brick Walls” isn’t is rosy or white washed. It certainly doesn’t pull any punches or try to ignore any of the harsher elements of Pakistani society, like corruption, violence and abject poverty.

What inspired you to write “Brick Walls”?

I trained the Houston Police Department on cultural sensitivity, as well as a few other groups. During these classes, people wanted to know about my life in Pakistan even more than they wanted to know about my life as a Muslim! I think Americans suspect that the media generated image of the bearded terrorist and the beaten wife are stereotypes, but they lack an alternative source for more accurate information. I thought I’d do the impossible and write a short story collection based on the true picture of a varied and complex Pakistan.

Why did you choose to write a short story collection instead of a novel?

When you read a novel, you want to focus on a just few great characters and a single story, but when I sat down to write, multiple storylines poured out. I didn’t want to force these disparate plots into a disjointed one, so I decided to write a short story collection. Interestingly enough, several reviews of “Brick Walls” point out that some of the stories in the book could be expanded upon into full novels, so I guess that may come at a later date.

What does ‘Brick Walls’ have to say to the Muslimah?

Actually quite a lot, because most of the characters in the collection are women—strong, resilient women. My intention was to showcase females as people, not as a gender. I wanted to explore how they react when faced with the tallest, most formidable barriers, and how they find it within themselves to do unimaginably positive things. That is what altMuslimah is all about to me—women supporting one another and breaking through the obstacles put before them.

What is life like for an immigrant Muslim woman today and why didn’t you write about that?

Fortunately, life as an immigrant has been good; I’ve achieved things I couldn’t have dreamed of living in Pakistan, for example, doing interfaith work and cultural sensitivity trainings. Perhaps, because I’ve enjoyed a relatively smooth ride as an immigrant, I don’t feel compelled to share my story. You write about what keeps you up at night, what gives you headaches and stomachaches! For me that nagging subject was my birth country, which I left so suddenly and without any real closure. Maybe in a few years, when I’ve said all I needed to say about Pakistan, I’ll write about the immigrant Muslimah experience.

Is there a connection between interfaith activism and storytelling?

Absolutely. I once went to a book signing to meet Eboo Patel, a popular youth interfaith leader, and he gave me concise but powerful advice– instead of talking about religion, tell stories. We often lecture on “what Islam says” or pull out statistics to make our points, when what really captures an audience’s attention and drives home the point are stories. I have found that “Brick Walls” has enhanced my work as an interfaith activist. Writing has honed my ability to describe situations and characters in an interesting way without sounding judgmental, and that’s the best way to talk about more contentious issues like faith.

Now that the book is out, what’s next for you?

I’ve written the first book in what I hope will become a series for girls aged 7-10. It’s a story about a Pakistani-American girl who pretends to be a ninja in order to fight bullies. I want my children to have stories about the issues they are facing, and if there aren’t any out there, then I’ll have to write them myself! I’m also working on a novel based on the blasphemy laws in Pakistan.

Saadia Faruqi grew up in Karachi, Pakistan and spent a considerable amount of time observing the dichotomy between modern and conservative Pakistani life. In her early twenties she married and moved to the U.S. She divides her time between raising her two children, working as an interfaith activist, and writing novels.

===

Excerpt:

A black Mercedes had approached their truck from the right, and parked itself in front of them at an angle, cutting off their path. Among the ramshackle houses that lined the broken street, the car looked even bigger than it was, and somehow menacing. She squinted as a tall and hefty figure emerged; the breath left her body as she recognized it. She hadn’t seen her brother in four years but his expression was the same as ever. Hard. Callous. Angry. She slowly opened the door of the truck and climbed out, reeling with the shock of seeing him so unexpectedly.

“Pervaiz, what are you doing here? Is everything all right?”

“Does everything look all right? You are sitting in a dilapidated old truck without a bodyguard and you ask me what I am doing here? You have been coming here to this cursed mud hole called Malir for two months, mingling with the scum of society, and you’re asking me if everything is all right?” He was bigger than she remembered, his moustache long and thin, framing a face no mother could love. His voice was low and menacing, which she knew was a bad sign. But she had attained courage along with maturity in the last few months, and she couldn’t let his opinions go unanswered.

“Scum? Is that what you call the people you are supposed to be serving? Have you forgotten why Abba Ji went into politics?”

“Abba Ji was a fool,” Pervaiz pronounced harshly. “It seems that you have taken after him.”

“Then I’m glad that I have taken after him, Pervaiz. I have found my calling. I am doing nothing wrong by helping these people. I’m doing something good. Why can’t you understand that?”

Rabia was confused as to why her brother was so incensed. She wasn’t asking him to join her. She knew that to do so would be futile. Why had he come here, she wondered? What harm was she doing anyone by volunteering at Helping Hands?

Pervaiz was pacing angrily on the road, looking distastefully around him as if he might contract a disease. He finally turned, his face stern and unmoving, ready to deliver his judgment. “You are to return with me to the village immediately. I have decided what to do with you.”

“Are you crazy, Pervaiz?” She couldn’t believe what she was hearing. “You can’t force me to do anything. I’m an adult; I can do whatever I want.”

Pervaiz smiled a chilling smile, and the image of a shark came impulsively to her mind. “You are so stupid, dear sister. Studying here in this sin city, Karachi, has led you to believe that you are free. I own you, do you understand? Your leash has been so long that you haven’t realized its presence around your neck. But now I am pulling you home, where you belong.”