I first learned about sex positive feminism in a graduate seminar at a large mid-western University. Every Tuesday and Thursday the long bare classroom would fill with students eager to talk about their hook-ups, their predilection for one or another kind of erotica and their general affirmation of the transformative capacities of the sexual act. For those who weren’t there, sex positive feminism stands for the precept that women are not free until and unless they are sexually free. In the competitiveness that graduate seminars breed, my classmates rambled on about threesomes, triumphant and unceremonious dumpings of emotionally attached lovers (who has time for that?) and in general lots and lots of sex. Our smug professor, nose-pierced and wild-haired and duly sporting the scarves and baubles of the well-traveled, encouraged it all. The question of how and when sexual liberation had become not simply the centerpiece but the entire sum of liberation in general never came up. The year was 2006.

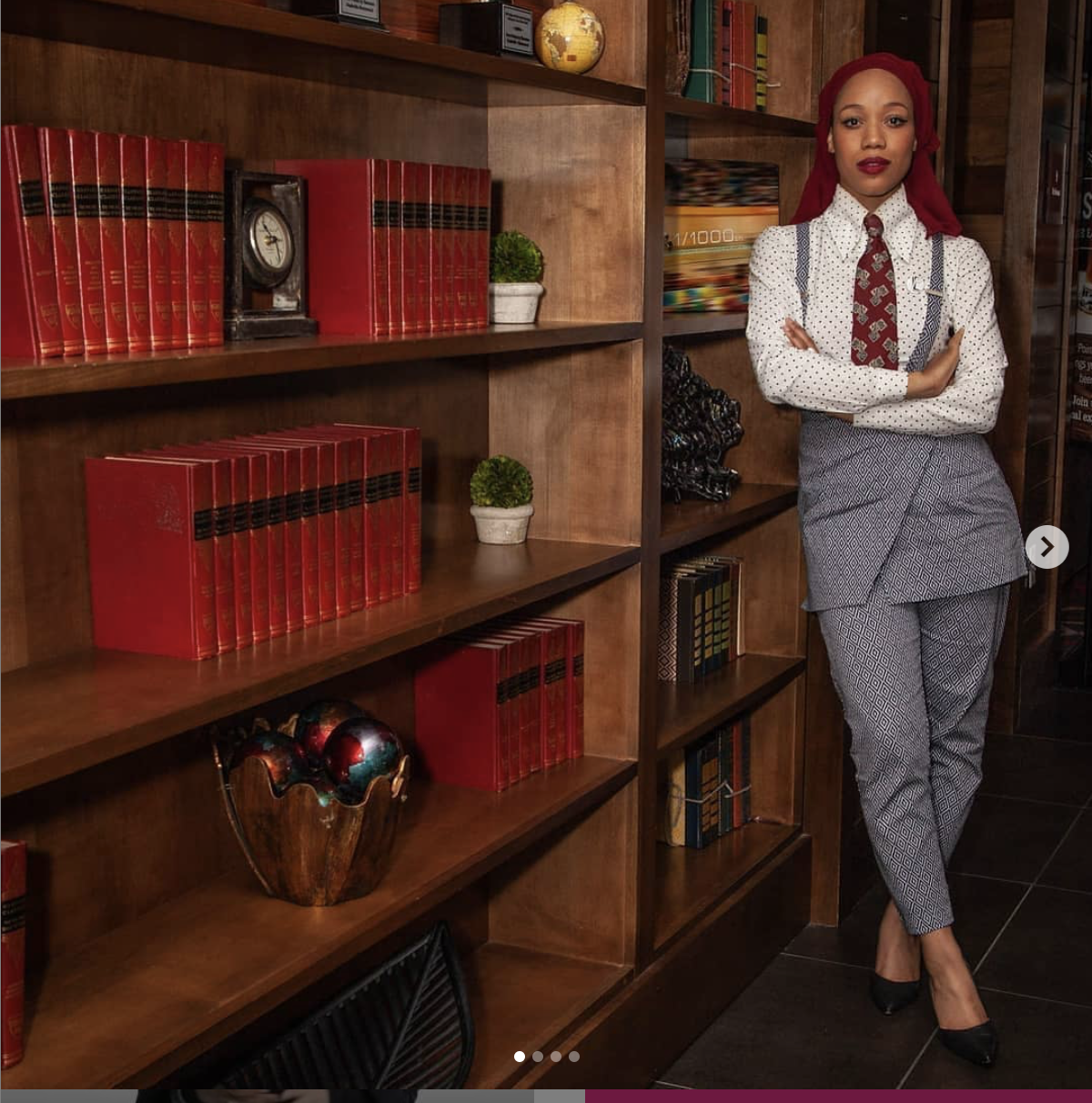

The Muslim feminist is either left out of the conversation or included only as an example of a deviant type, demanding liberals’ suspicion and vigilance.

I was disappointed but I said nothing. I had cuddled up with alienation just as soon as I began my graduate program. I wasn’t older but I was divorced and a mother; I spent a lot of my time juggling money and precarious childcare. At the time I took the seminar, I had just returned from Pakistan, where I was from, still bruised at having to explain my life choices to a family that had never before seen a divorce. In Pakistan I had worried about somehow losing custody because children were seen as part of the father’s family; in American courts I had had to explain my fitness as a mother because I worked and went to school all day. I agreed with sexual liberation as a portion of liberation in general; I wasn’t convinced that it was the whole.

That was not the only reason I kept quiet. Being Muslim and female was an identity that rhymed effortlessly with repression and oppression in the view of most liberal academics and students. I had heard it all so often and in so many other classes: the interdiction of the hapless women who were imprisoned by Islam, as an offhand way to highlight the relative fortune of the more successful Western feminist, the one that had moved from questions of basic equality to concerns with sexual pleasure. No texts by Muslim feminists were assigned reading for the course: not Leila Ahmed’s Women and Gender in Islam and not Amina Wadud’s Qur’an and Woman. The course’s sole concession to diversity a single slim text—Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza—by the Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldua.

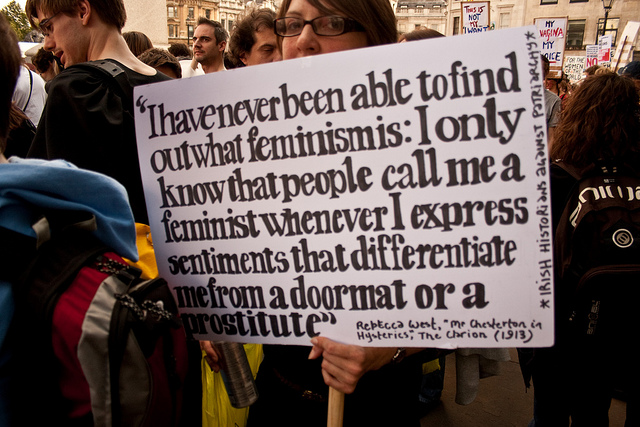

That curriculum was chosen nearly a decade ago, but the exclusion of Muslim feminists has continued. In an interview published in the New York Times last week, feminist icon Gloria Steinem, whose latest memoir was published last month, named twenty-eight women and three men in her list of “best contemporary feminist writers.” She fails to mention a single Muslim feminist. In other instances, I’ve found my own writing on women and militancy attacked; not met with analysis and engagement, but with condescending suggestions that, because I am female and Muslim, I am somehow “excited” by the idea of a female Muslim warrior. While the tone and tenor of these may vary, the message is the same: The Muslim feminist is either left out of the conversation or included only as an example of a deviant type, demanding liberals’ suspicion and vigilance.

I realized this even then. Contesting the premises of my professor and classmates would label me the prude, the insufficiently liberated. Speaking would court encirclement by pitying, knowing glances reserved for one understood to be plagued by yet un-confronted repressions. If I spoke, I would give them what they wanted: a Muslim woman to save, to school in the possibilities of sexual liberation.

It would be impossible, in the rush and fervor of that savior encounter, to explain that my oppositions were not at all to sex or sexual pleasure, but to its construction as unproblematic, un-colonized by patriarchy, the entire measure of liberation. A Muslim feminist, I was sure, could not make that sort of nuanced distinction.

Read more.

Photo Credit.