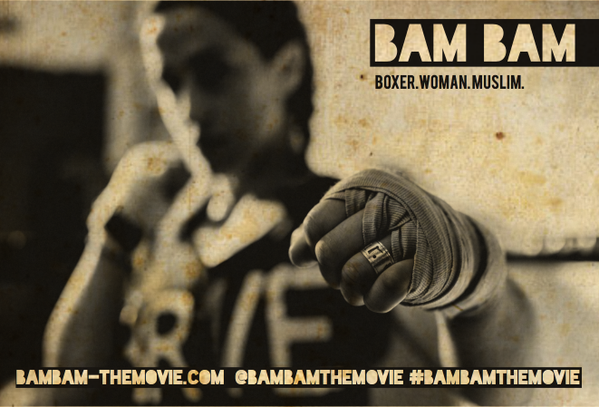

An Australian boxer talks to Maria Khwaja Bazi about being a Muslim woman and someone from an ethnic background.

Bianca “Bam Bam” Elmir is dressed in a sky blue shirt, squished on a Skype screen on an early morning in Melbourne. Although she is half a world away, her energy is evident even through a screen. Next to her is Jemma van Loenen, the producer of Bam Bam, the documentary.

We establish her history immediately: “I come from a Lebanese background, my grandparents migrated in the ‘50s to Australia. I was raised in Canberra, where I’m based, by a single parent, my mom, who divorced my dad when I was very young. I was 2.”

Shifting slightly, she adds, “I met my dad at 27 properly; we’ve had a very loose relationship since then. My mom, on the other hand, has raised me on her own.”

It is not the first time in our conversation that I am surprised by Bianca’s candor. She is direct, open, occasionally pushing back her curly hair and shifting as she speaks. The Australian boxer is evident even when she is seated not just in her body, but in the way she moves occasionally, unable to sit totally still.

Spiritual Moments in the Ring

The tagline to Bam Bam the movie is “Boxer. Woman. Muslim.” I ask Bianca about the Muslim part, first, curious as to how she defines herself in this regard.

“My mother, she didn’t really have a strong connection to the faith growing up … she didn’t wear the scarf and she didn’t pray,” Bianca replies. “She’s becoming more devoted as she’s grown older. At 13 or 14, my attachment to Islam was the strongest in my life. It cemented my identity.”

She pauses, and then continues: “Since then, I’ve changed, and the religion has changed with me. I still consider myself a strong believer. I feel like my faith is at the center of who I am and everything I do. Boxing, for me, is something very close to my heart because it’s raw.”

Bianca’s unexpected shift toward discussing boxing in the midst of discussing Islam throws me slightly, but she finishes her thought with an eloquence that I’m beginning to see is an indisputable part of her.

“It’s very close to my emotions: being a fighter and sticking up for what you believe in and believing in yourself and have the most acute focus and focus to detail. I feel like my faith enhances those elements in me. Islam is about sticking up for what you believe in and fighting for a cause and believing so deeply in something and committing to it. I think [boxing] runs parallel to that. It’s a very spiritual moment in the ring.”

When she says this, I immediately think of the traditions of Muay Thai, or Thai Boxing. In a traditional Thai fight, a number of ceremonial rituals, including the Wai Khru Ram Muay dance and the wearing of mongkol (or mongkon) headdress, form an enormously important part of every fight.

Bianca, who has a background in mixed martial arts, confirms my thought when she continues: “When I come in and out of the ring—we get these traditions from the Thais, the blessings coming in and out—I thank God. I don’t necessarily thank the spirits, but I thank God, always, for my opportunity in the ring, whether it’s training or fighting. In the moments of despair when I’m at my wit’s end and I’ve got someone trying to take my head off in front of me, I have a second of self-doubt and that’s when I turn and restate to myself that myself that I believe in God and myself and this opportunity and this moment.”

“My religion gives me a lot of inspiration,” she finishes, simply.

I wonder if Bianca’s experience of religion is reflective of a very private negotiation of her Muslim identity, without the input of a larger Muslim community.

“In a way, yes, I look at other young people … it’s a confusing time in that you’re trying to figure out your identity, how you fit into the particular community you’re a part of, and if you’re a part of a diaspora that doesn’t have a lot of momentum, you feel like you have to shout a bit louder. With the religion, I felt on the periphery—living in Canberra, it’s a very middle-class, white suburban city, I always felt a little bit on the outside—anyway, even though it’s a very inclusive space, I felt like I had to stand up from when I was very young.”

The idea of growing up surrounded by a different, dominant narrative is so similar to my own childhood. I tell Bianca that I went through the same process of identity negotiation and she nods, continuing: “Having the religion as a label, being Muslim at the time, gave me comfort and gave me that pathway, especially being quite a young person, I was searching for that. Kind of similar to you, I didn’t need to shout as loud about needing to verify who I was. I was more comfortable having nuances about being a girl, a Muslim, someone from an ethnic background.”

She pauses, laughing: “So, having all those different narratives, I’m still nostalgic about those days because things were so clear and I was confident about how things were right or wrong. Understanding what is evil and what is not evil. I feel like I’ve got a more progressive understanding of the religion, now. Community work, care for the people around me, care for the people that were ill—[Islam] instilled that in me and I still hold on to that, treat people with respect, if someone is poor, look after them. You have to help people in need. Those are the things that have stuck with me.”

Identity and Femininity

When she pauses, she and Jemma both look at me expectantly and I sheepishly admit that, from the trailers for Bam Bam, Bianca comes off as far more aggressive and defiant than she does in person, where she is immensely articulate and thoughtful.

Bianca laughs: “I feel like I’ve become quite masculine. My particular gym is only boys, so I’ve had to take on a persona which is a little, you know, thick-skinned. Can take anything, can take all kinds of comments, can take any guy they put in front of me, so I think I’ve developed that quite well over time, out of survival. My coach has a lot of confidence in me but then will also put me in front of anything.”

She shifts a little, still grinning: “I think at times, ‘I’m getting my head pummeled in and I don’t know what’s going on.’ Through self-preservation, I’ve had to take on this persona of toughness and true grit, bite down on my mouth guard and get through everything.”

Jemma, looking a little startled, adds: “That’s interesting, I didn’t realize that was coming across. I wanted to create some kind of in that, there’s a goal she’s trying to achieve and there’s been obstacles to overcome, like the ban … but also to balance that with what gets Bianca through.”

She adds: “I did have a little snippet that I wanted to put in there, there’s a snippet of you rubbing your face and you say you like having your face patted, to balance this full on aggressive thing where people are punching you in the face. You have that need to be nurtured.”

Bianca smiles playfully and says, to me this time, “I just want to be hugged.”

“Being in a highly sexualized environment,” she continues, pausing briefly to become more serious again, “I don’t want to come across as too cute and too much of a princess. Maybe I’ve gone too far the other way. I’ve found at times I need to re-center and ground myself; I find myself losing a bit of my identity and femininity, which I really embrace and love about myself. The paradox is really difficult.”

Many female fighters and athletes, including Serena Williams and Ronda Rousey, contend that being “feminine” and an “athlete” are not mutually exclusive. While Bianca seems to agree with this, she also contends that the traits of aggression and dominance visible in boxing are male traits that she must take on in order to survive. In a way, she must “fight like a man” while still finding ways to express her femininity.

“Feminine, to me, is maybe having a more nurturing, a more humble side, a caring side. Feminine is being more considerate—I see it as all of those things. I don’t express those things in the ring; otherwise I’d get my head punched in. So then I express my femininity through dancing—I’m always dancing around in the gym. It’s quite sexualized dancing, sometimes, but it’s the one space I know no one can take from me, where I can be chill and be a girl, I can feel my body and I can dance.”

She pauses and looks at Jemma, thinking, and Jemma adds: “It hasn’t necessarily come through yet in the trailers, but it’s definitely something we’ve talked about and we’re interested in.”

“It’s almost like this alter ego has become me,” Bianca says, smiling again. “I’ve got this persona and I’m so mindful. I don’t even let men go through that. It’s fascinating looking at the person I was a few years ago to what I am now. I would walk into an office as a political advisor with beautiful skirts and high heels and jewelry and I was the face of the office.”

I can’t help but think that Bianca’s blunt admission that yes, she does have to take on what she defines as masculine characteristics is almost more honest than most negotiations about gender.

“All those things are amplified in the sporting world. I have to hold my own, and if I’m emotionally fragile or I’ve had a bad day and I want to cry, yell or scream, I have to hold out on my own. My coach isn’t going to hold on to those things. I’ve chosen a sport that really amplifies it.”

“It’s a very fine line,” she continues, “I’m not going to dumb myself down or make myself ugly just in case you find me sexually attractive—you have to own that and you have to be responsible. But don’t cross my boundaries. If you want to admire me, that’s fine as well, but first and foremost I’m an athlete and I want to be respected for that. Honestly, if there was a whole heap of other girls at the gym, I might find that threatening. There was a girl that came once and she had a bit of a sulk about the weight we were working with and I blanked her.”

She finally, in the interview, shows the aggression that is so evident in the movie trailer: “Don’t put me in your ‘please help me circle.’ I worked hard for this. I’m going to lift this weight and I can do it. I had to spar her, I sparred hard, and she never came back.”

When Bianca sits back a little, pausing, Jemma adds that they have been trying to explore the ideas of aggression and the labels imposed by society.

Bianca leans back in and says, “The debate is so interesting, anyway: to be feminine, and through Islam on top of that, where feminine is such an external experience, it’s understood to be external. Femininity is something very personalized and it’s centered in the private sphere and celebrated amongst women.”

She continues thoughtfully: “But I’m living in a Western country. I never really felt like I needed to wear a short skirt. I felt like I went the other way, I felt like one of the boys, so I got the label ‘tomboy’ which I find so derogative. I hate the word. I box in a skirt just because, because girls will try to show that they’re just as good as the guys and wear the same thing as the guys, but that’s why I wear a skirt, it looks good on me and is different.”

Fight or Flight

There is no question that Bianca is a bundle of contradictions: articulate, aggressive, spiritual, sexual. Yet this is perhaps the most intriguing part of her: the constant, ongoing negotiation of her identities. While other women attempt to straddle precariously, Bianca is defiantly who she is with very few apologies.

“I moved out when I was 21,” she explains. “I was ostracized, I was on my own, traveled on my own, lived on my own, got myself through university. That was hard. I was young and I really had no one else. I had no family at all, so whilst I can sit here and say, very confidently, yes, this is who I am and say that, this has been a hard road.”

When I ask her who she is, she replies, “The fighter narrative. Fight or flight. I fought back for myself, for what I wanted to do, for the person I want to become. I could quite easily still be living at my mom’s house, gotten married, become the person she wanted me to be, put on a headscarf and been done with it. I didn’t.”

As we begin wrapping up our conversation because Bianca must prepare for a flight, I am particularly interested in her feeling that she negates some of her femininity and sometimes, in her own words, uses it to “manipulate men.”

“I feel like I can get it over any guy, it’s really interesting because I express it when we have these big kickboxing events,” she says, smiling again with an ever-present charm. “It’s when I get the chance to dress up, that’s really when I can cement my femininity, the juxtaposition of who I am. I love the shock element and I find people treating me totally different. I’m the sexy girl, I like playing that role.”

“I know that deep down,” she says, pausing ruefully, “I’m still a woman. I feel like I have these sides of me where I do want to care for people and treat them kindly. With men in particular, I feel like I need to conquer them. That might have something to do with it. Maybe it’s my daddy issues, I probably do have daddy issues.”

She chuckles again, grinning at Jemma and myself: “At least I’m self-aware! I’m lucky I’ve had that self-reflective part of me for a very long time. I’ve been analytical in writing diaries and I’ve always had someone to confide in. Being open and adaptable to change, I feel like I’m open to what life presents.”

Even first thing in the morning, this woman’s charisma is evident. Jemma, the producer, has been a quiet presence throughout the interview, but it is Bianca who has taken center stage without much effort.

“You Are Worthy”

As Bianca gets up with a cheery wave to begin preparing for her flight, I ask Jemma why she chose Bianca as a documentary subject.

“I want to give a different angle,” Jemma responds, “from what is out there on Australian TV and cinemas, something that is a little left field, and I guess connect it with that sort for people about following a dream. The plotline for Bianca is to be a world champion—to be the best at something, everyone has that dream in some form or another, in whatever career or vocation that’s in, but it’s too easy for us to lose that. It’s easy to doubt and fear and to give in to those things.”

We say goodbye and end the call, but in the silence afterward, it is Bianca’s final thoughts on what to say to other young Muslim girls that resonate with me.

“My message is that throughout your journey, which you need to define yourself, there will be moments of anxiety, fear and doubt, and all of those things are okay and they’re a part of the journey,” she says.

“It’s really important in withstanding those emotions that you cultivate self-belief and that way that you can do that is just by working really hard, looking at yourself in the mirror now and then, revisiting your own eyes, and looking deep into those eyes and telling yourself you are worthy.”

[separator type=”thin”]

This article was originally published on Fair Observer, and was featured with permission.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Lollapalooza Films / Phill Northwood