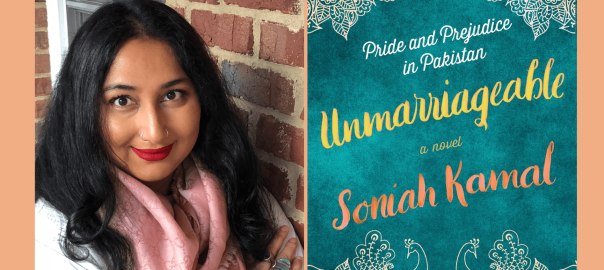

Author Soniah Kamal (An Isolated Incident) is out with a new novel, Unmarriageable: Pride and Prejudice in Pakistan. Here’s a quick summary:

A scandal and vicious rumor concerning the Binat family have destroyed their fortune and prospects for desirable marriages, but Alys, the second and most practical of the five Binat daughters, has found happiness teaching English literature to schoolgirls. Knowing that many of her students won’t make it to graduation before dropping out to marry and have children, Alys teaches them about Jane Austen and her other literary heroes and hopes to inspire the girls to dream of more.

When an invitation arrives to the biggest wedding their small town has seen in years, Mrs. Binat, certain that their luck is about to change, excitedly sets to work preparing her daughters to fish for rich, eligible bachelors. On the first night of the festivities, Alys’s lovely older sister, Jena, catches the eye of Fahad “Bungles” Bingla, the wildly successful—and single—entrepreneur. But Bungles’s friend Valentine Darsee is clearly unimpressed by the Binat family. Alys accidentally overhears his unflattering assessment of her and quickly dismisses him and his snobbish ways. As the days of lavish wedding parties unfold, the Binats wait breathlessly to see if Jena will land a proposal—and Alys begins to realize that Darsee’s brusque manner may be hiding a very different man from the one she saw at first glance.

I admit, somewhat shamefully, that even though I’ve read Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice, I don’t remember any of the details. So, at first, I found myself ill-placed to review Soniah’s retelling of the story. Many of the reviews of her book turn on how well the stories and the storytelling match up, the likeness of the characters, and even some of their names (“Mr. Darcy” is “Darsee” in Soniah’s retelling).

But there were so many parts of Unmarriageable that were familiar to me—not because of my distant memories of Austen’s book, but because of my lived experience as a first-generation Pakistani-American. To be the daughter of upper-class Pakistani immigrants to America means, in many cases, to be both (1) a staunch believer in women’s rights and the value of women’s education and a career; and (2) a participant—willing or unwilling—in traditional performances of femininity. If we think of the space between these two positions as a spectrum of sorts, the five Binat sisters each occupy their unique place along the spectrum. The protagonist in Unmarriageable, Alys Binat, takes the centrist position, both embracing her role as teacher and intellectual but also largely willing to go along with the dress-ups; Lady performs femininity in an extreme, almost unbecoming way; Jena takes on femininity in its subtler form; Qitty largely refuses to conform to external standards; and Mari … well, Mari is the religious peanut gallery.

There’s another part of Unmarriageablethat resonated: the total and complete political incorrectness of Mrs. Binat. To be Pakistani-American means I’m a part of an increasingly politically correct American society, and also part of a still-very-politically-incorrect Pakistani culture. Parts of Mrs. Binat’s character shocked me (and my American sensibilities) and parts were just pure fun. Soniah does a great job of writing dialogue that is fast-paced, at times cutting, at other times tender and loving, and altogether reflecting many conversations I have had with Pakistani family members both in the U.S. and in Pakistan.

I also loved the descriptions of Pakistani clothes (in particular, the carefully orchestrated looks for various wedding events) and Pakistani food. As an American-born Pakistani, when I think of my parents’ homeland I think of its food and clothing. These are the elements of my heritage that I savor, and that I pass onto my kids. To see Soniah describe it in all of its lush detail was delightful, or as many of her book’s reviewers have called it: “delicious.”

I had the chance to talk with Soniah about her writing process, and her inspiration for Unmarriageable:

Asma: Soniah, thank you so much for this really lovely story. I had so much fun reading it. I can see the obvious similarities between the culture Austen describes and upper-class Pakistani culture – was it this obviousness that inspired your retelling of the story, or was it something else?

Soniah: Thank you, Asma! I’m so glad Unmarriageable was a fun read for you. There were a few reasons I wanted to do a parallel retelling of Austen’s classic novel and set it in Pakistan. I first read Pride and Prejudice when I was sixteen and though I was smitten by feisty Elizabeth and the butting-heads love story, it was Austen’s wit and ability to capture her characters’ hypocrisies and double standards that had me riveted.

I have grown up in England and Saudi Arabia and though I’d spend summers in Pakistan, vacations are one thing and returning to live, which I did in the ninth grade, another. In Saudi Arabia I went to a co-ed international school which resembled a mini-United Nations and to suddenly be in the all brown people Pakistan at an all girls schools and immersed in a culture where class, money and status seemed to be everything, made me very uncomfortable.

I’d be been taught at home, and in Islam, that everyone deserves equal respect. I was also amazed at all the talk of ‘good families’, meaning wealthy or, in the absence of wealth, religious piety, and ‘good girls’ meaning girls who were demure, obedient and submissive and unlike me would not dream of wearing a jacket with Lois Lane and Clark Kent kissing or asking their Dad that if he smoked why couldn’t I? Lungs were lungs. This was the late 80s and early 90s and a girl like me who talked back and had multiple ear piercings (six in each ear) etc. was immediately labeled slutzilla by peers, teachers, society.

It was very hard. I saw all this stress of honor and reputation reflected in Pride and Prejudice as well the obsession with marriage being the supreme goal for ‘good girls’. Since I disagreed, this made me a bad girl like Elizabeth Bennet who rejected two proposals—I was so impressed by Lizzie’s confidence to say No. Pride and Prejudice’s world seemed such a reflection of much of the Pakistani milieu I found myself in that it seemed a natural next step to want to write a retelling.

The other big reason was colonialism and Thomas Babington Macaulay’s 1835 language policy. At the Unmarriageable launch at Elliot Bay Book Company in Seattle, Professor Nalini Singh said that “Unmarriageable is Macaulay’s nightmare.” True. In fact, one of Unmarriagable’s epigraphs is a quote by Thomas Babington Macaulay’s 1835 address to Parliament proposing his creation of ‘confused brown people’, and I also end with him in the essay accompanying the novel. I love Jane Austen’s social satire and, as far as Macaulay was concerned, as a brown person that love should be enough. Instead, I took Pride and Prejudiceand reoriented it, making the classic universally South Asian and in particular Pakistani.

Mrs. Binat’s blunt assessment about women – their looks, their worth – can be shocking for a typical American reader. What are some of the responses you’ve received to Mrs. Binat specifically?

The overwhelming response is that Unmarriageable’sMrs. Binat is a sympathetic character rather than just a caricature of a shallow fool whose one goal is to get her daughters married off. In Regency England, marriage was the only way a woman from Mrs. Bennet’s class was allowed financial security. In contemporary Pakistan, where women can work and out earn a man, mothers like Mrs. Binat yet have their reasons for emphasizing marriage and I worked on showing those reasons and why they seem valid to such women. Readers from other cultures think she’s a hoot and a can be a bit over the top but Pakistani readers immediately recognize Mrs. Binat in their own mothers and Aunties. In fact, readers from more traditional cultures– Italian, Irish, Greek, Jewish, Nigerian– don’t find her exaggerated either.

Mari is interesting. She’s probably the only character in the book that captures what many Americans think of when they think of Pakistan: religious demagoguery. I don’t think many people even realize how that demagoguery is far from the norm, and that Pakistan’s upper class is better known for its colorful (at times scandalous) clothes, globe-trotting, and lavish parties. How did you think through her character and what did you hope to show the reader by including her?

Dawn, a national newspaper in Pakistan, point out in their review of Unmarriageable that “There is, in Kamal’s novel, notable attention to detail when it comes to situating characters within a specific class context that Anglophone Pakistani fiction rarely manages to accomplish.” I worked extremely hard on featuring characters from many classes and backgrounds in Unmarriageable. However this was not done because Americans, or whoever, were going to read this but because this is the Pakistan I grew up in and know and this is reflected in the religion too.

As a minority writer, it’s easy to be thrust into the role of ambassador or representative of a certain culture or religion but I think it’s important to not play to the burden of representation. An interviewer asked me if I’d written Unmarriageableto educate Americans. Unmarriageable is not a textbook, it’s a novel. I did not think ‘The West is going to be reading Unmarriageable and so it is now my duty to write only angelic or monstrous Muslim characters.”

My job as a writer is to write a fully realized world and characters without any authorial agenda catering to any reader’s expectations—Western or Eastern. The beleaguered Mari is quite self-righteous while other characters are not at all. Jane Austen’s father was a Reverend. All of Austen’s novels have clergymen and she exposes their self-righteousness. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Collins is a clergyman and a pompous, self-serving one at that. However, there is no representative man or woman of the mosque in Unmarriageable. Instead, all my characters inUnmarriageable have different degrees of religiosity which is very much the case in Pakistan, where the same family can have members who pray the mandatory five times a day while others may just pray once or not at all.

One of the tenets in Islam is that ‘there is no compulsion in religion’ and that ultimately everything is between you and God. This is the philosophy Unmarriageable is set in. As in Austen, everyone in Unmarriageable has their flaws, the religious, the not-so religious, and the non-religious. Unmarriageable also reflects Pakistan’s religious diversity and one of the married couples in the novel are Muslim and Christian. Of course, it’s important to remember that there is no one monolithic representation of Islam and that the practice of any religion is often influenced by the culture in which it resides.

Pakistan’s Islam is very different from that of Saudi Arabia’s. And the Islam practiced in an immigrant community, in say, the U.S., is different from community to community. In my first novel An Isolated Incidentfeaturing a Pakistani-Kashmiri-American family, the father is an atheist, the mother a practicing Muslim, and their kids are all over the place. To bring up my favorite quote: ‘There is a no single story’ and in Pakistan, in all countries, the class you come from and then the family within that determines so many of your choices. For instance, I was allowed to go abroad to study but I was not allowed to become an actress. Was my family liberal or conservative?

“Fart Bhai” ends up being a surprise of sorts. I admit I expected him to be a misogynist in the way you described his initial interactions with the Binat family. But he turned out to be a generous and gentle husband to Sherry.

Farhat Kaleen also known as Fart Bhai and my version of Mr. Collins is very much someone who could easily belong to the Christian purity culture. These are men, and women, who believe that the male is the head of the household and women are the helpmeet and to be protected and taken care of. Of course this world views means subservience and obedience to the husband. In their eyes they are living a lifestyle they believe is best and will eventually take them to heaven. As long the wives and children behave, they can certain be generous and gentle. Issues arise if when you’ve got a daughter who says ‘if you smoke why can’t I?” or a child who is, for instance, LGBTQ. Basically, rebellion of any kind. Actually both Fart Bhai and my Jaans (Mr. Hurst) are a contrast in a kind and unkind misogynist.

The story ended so neatly…the perfectly-tailored happily-ever-after. Alys, in the end, didn’t have to choose between living a life of riches and comfort, and living the life of the mind.

Alys Binat’s happily-ever-after mirrors that of Elizabeth Bennet’s. As this is a parallel retelling, I had to be faithful to Austen’s storyline even as I gave the Bennet sisters and all the other characters their own original spins. Qitty Binat faces fat phobia. Lady Binat is constantly slut shamed. Jena Binat realizes that not everyone is as nice as they pretend. Mr. Binat realizes that family is not always family.

Many of the characters names mirror Austen character’s names, however in Unmarriageable all the names come with their own histories and origins. For example, Darsee is a mutation of darzeewhich means tailor in Urdu and Wickaam has a double a because aamin Urdu means ordinary. Jeorgeullah was my one indulgence, a joke my best friend and I share about a TV show that used to run in Pakistan called “George Ka Pakistan” (George’s Pakistan). There is a reason the novel is set in 2000-2001. Writing a parallel retelling of Pride and Prejudice which features the original plot as well as all characters even as I gave Unmarriageable a contemporary spin and characters with their own unique arcs was very challenging.

Asma Uddin is the founding editor-in-chief of altM.

1 Comment