Most insults aimed at Muslims are far from subtle. It is easy to recognize the affront, for example, when someone says she is tired of people saying Islam is a religion of peace, or sponsors ads in subway stations implying Muslims are “savages.” But sometimes the bigotry is subtle. Sometimes it comes from people who have been lovely to you, hosting you, feeding you fancy pastries and asking for your signature.

One of the best parts of being an author is visiting book clubs. As the author of a novel about Muslim women, I am often touched and encouraged by how non-Muslim readers relate to my book, and how they share so much of themselves with me in return. But at a recent book club visit, something less encouraging happened. Someone raised the issue of whether individual Muslims should condemn terrorist attacks done in the name of Islam. I explained that this is a complicated, emotionally fraught decision for many Muslims, who are the only group asked to make such public condemnations and who are so often ignored when they do.

It was not complicated at all for one of the women, who insisted that Muslims must do it. “If we are going to try to accept you,” she said, “you have to meet us half way.”

And there it was: Her casual separation of non-Muslims into “we,” and Muslims into the other “you.”

I’m a white woman married to a Pakistani-American man. His family moved to the United States when he was three, because they wanted more opportunities for their children. Together, we have two kids of mixed heritage and an African-American son. I was born in California and raised in the Midwest, graduated from one of the oldest women’s colleges in the country, and, like my husband, received a law degree from a top-ranked American law school. We have two beloved dogs and one unsettling lizard. I have a weakness for Mountain Dew, Dance Moms, and Kate Spade shoes. I live in Boston but adore the Yankees. I vote. I passed two bar exams. I wrote a novel. The last time I wept was while watching the interfaith memorial service for the Boston Marathon victims. To me, all of this feels pretty American.

But I’m also a convert to Islam. And that means that even for a gracious woman in a cozy New England living room, I am still the other, the one it requires some effort to accept.

Contrary to the rantings of some pundits, my religion is not a political ideology. It is a spiritual system of belief which tells me to care for orphans and the elderly, and that I am not a true believer until I want for others what I want for myself. I remain within a prophetic tradition that includes Adam, Abraham, and Moses. I embrace the work of pro-woman Muslim scholars. I trust in the very first line of the Qur’an which states that God is the most gracious and merciful. I believe in second chances, divine forgiveness, and the simple charity of a smile.

The most common reaction to my novel I’ve had from fellow Muslim women is profuse gratitude for portraying Muslim women as “normal.” That word shows up repeatedly from both liberal, secular Muslims and conservative, traditional ones. What they mean is not that my characters are western, although arguably they are, but that they have normal human emotions and worries and lives. That they are not some “other” sitting around figuring out how to blow everyone else up or cowering before caricatures of abusive husbands.

Writers strive for verisimilitude, and I am no exception. Contrary to prevalent stereotypes, Muslim American women tend to lead very normal lives. Gallup research shows that we are more educated than the average American woman, second only to Jewish American women, and that we have more income parity with our male counterparts than any other group of women. I’ve been asked several times why I wrote about “privileged” Muslim women who are educated and have interesting careers. It’s because that is the experience of so many Muslim American women — though we are most often considered something to be pitied — and so few people seem to know about it.

A simple Google search reveals the strong Muslim feminist movement, the ways Muslim women are fighting for their rights both within and outside of Islam. Muslim American women are scholars and businesswomen, advisors to U.S. politicians, leaders of religious organizations, tireless activists and acclaimed authors. We are even the new Ms. Marvel super hero. Whether we cover our hair or don’t — the praxis to which the public seems most likely to reduce us — Muslim American women are kicking butt and taking names.

How sad that the media has done such a wretched job of portraying us. That it is heartbreakingly rare for us to see accurate portrayals of our lives. That we hunger simply to be shown as “normal.”

Here is the truth: The “normal” Muslim women in my novel are actually phenomenal. They are at the top of their careers with Ivy League educations. They are brilliant and engaged and funny and loyal. That’s because they are similar to many of the Muslim women I know in real life — women who it should require little effort to accept, whom others should rush to meet halfway.

It’s time for the media to ask more of itself when portraying Muslim American women. Relentlessly trafficking in stereotypes hurts Muslim women in obvious ways. But it hurts non-Muslims as well. When you hide an entire group of women behind lazy, monolithic, and often inaccurate clichés, you impede the understanding and respect that come when people from different backgrounds get to know one another. You discount that we have something to learn from each other. You preclude the possibility of affection.

In effect, you keep us from being friends, and that is a loss for all of us.

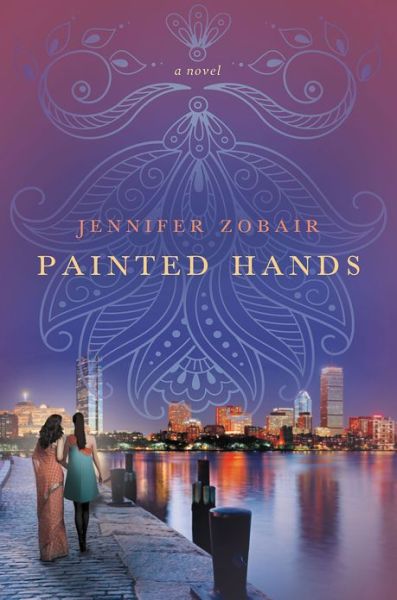

Jennifer Zobair grew up in Iowa and attended Smith College and Georgetown Law School. She has practiced corporate and immigration law and as a convert to Islam, has been a strong advocate for Muslim women’s rights. Zobair lives with her husband and three children outside of Boston. “Painted Hands” is her debut novel. For more information, please visit http://www.JenniferZobair.com This .piece originally appeared in The Huffington Post.