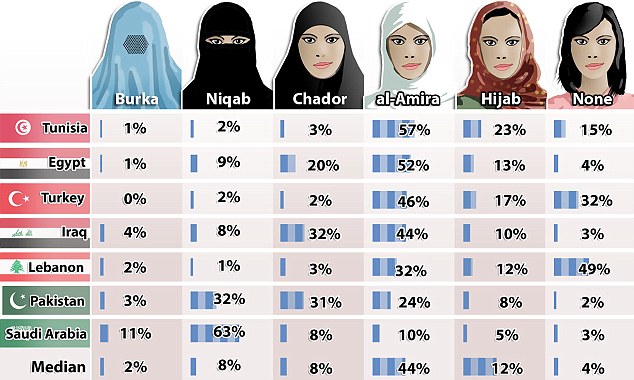

A recent Pew Research Center study indicated how “people” in various Muslim countries “prefer” Muslim women to dress. The results are varied from fully veiled dress to no veil at all. There seems to be no turning away from public interest in Muslim women and the flurry of commentaries from public intellectuals has begun. Beyond the polemics of discussions on Muslim women, I’m interested to interrogate the notion of “preference” in this matter and ask, “Who are these ‘people’?”

Issues of women and veiling may seem simple at face value but in fact, they are complex and require interrogating a variety of themes and concerns in Islamic cultures and societies.

The way in which anyone covers his or her body is bound to considerations of gender, culture and politics. I guess in some way, no one is independent regarding what they can and cannot wear; we are still restricted on how we dress ourselves, which leads some individuals to attempt to impose clothing ideals on to others. I can’t help but think back to the images of the formally clothed, white colonial male anthropologist who sits beside the unclothed black woman’s body. Without a word being spoken, a thousand statements are made. Clothing and veiling equally play a central role in Muslim societies, where citizens return to concepts and constructions of what godly modesty means in Qur’anic terms, the inimitable words of God that, in my view, have always left room for personal interpretation.

We may think some gender issues have moved on in the twenty-first century, but we still live in a world where Muslim men have become spokesmen, in its most literal sense, for all matters on Muslims. Some Muslim men speak for both themselves and women, while Muslim women are often expected to speak only on matters of Muslim women.

In terms of veiling and clothing, both men and women are quick to judge individuals on how they dress. For example, when a fully veiled women stands next to a woman who does not choose to veil herself, the viewer will immediately connect some past understanding or visual of the two. Yet, when we place the two women in conversation with a voice, without the commentary of men, the dialog might surprise us.

More than just commenting on clothing, there may well be a deeper issue at stake: authority. Issues of gender and sexuality are inextricably bound to power and these issues within religious communities and societies are bound to authority. I think in some way, the presentation of monolithic, static constructions of Muslim men and women helped to control and retain power in Islamic societies. Yet now, more than ever before, this romantic notion of an “ideal” Islamic state, with its closely linked to ideas about maleness and femaleness, is diminishing. So who holds the authority now? This very question is allowing Muslim individuals to find their own voices.

Globally, Muslim communities are now debating whether Muslim women can lead a mosque. Muslim communities are now debating responses to the numerous categories of Muslim sexualities. Muslim communities are now debating who has the right to confer and deem something “Islamic” or not. These core issues of contention are without a doubt bound to Islamic masculinity and femininity.

have spoken to Muslims across the spectrum: from a Muslim woman in Scotland who wants live a life free from the Mosque yet clearly has a central place for God in her life, to a Muslim woman in Pakistan who wants to live under stricter traditional, law abiding tenets. Interestingly, both of these women wanted me to tell them if what they were doing was “right.” I laughed. The important point I wanted both of them to note was that piety is a personal matter and no one, especially a man, has a right to tell a woman how to live in a particular way. The umbrella of “Islam” has the capability to sustain every variety of Muslim. The paths of both of these women are within what Islamic traditions tell us is the “right path.”

Just the other day I made comments about this topic on the “Wall” of a Facebook friend. I was immediately told to re-evaluate my comments because the prophet Muhammad wrote about Muslim women. This may well be true, but the prophet Muhammad, or any other prophet, is not God and the Islamic message of God that leads to gendered acts of piety, belief and submission, are indeed individual acts. Islamic prophets within the traditions are messengers to announce the existence of a god. This should come as no surprise given that even Qur’an commentators and Islamic jurists were the first to declare that their opinions were exactly that: options. They said it was up to Muslim men and women to accept or reject their opinions and “God knows best.”

Because an unseen god presented an ambiguous message, maybe the “existence” of “God” helps one to unshackle his or herself from the restrictions posed by a fellow human beings. Taking restrictions out of this world creates a recipe for gendered and sexual liberation. The inevitability of diversity in faith was something that even prophets could not restrain.

Don’t get me wrong on this one- I’m not advocating silencing anyone but what I do think will be a step forward is for Muslim men to shut up on issues around Muslim women. The so-called “Islamic reform” that the world seeks has been happening since the beginning of time but to really appreciate it, one must read between the silences and not accept the voices of the loudest, most often men.

Amanullah De Sondy is Assistant Professor in Islamic Studies at the University of Miami and the author of The Crisis of Islamic Masculinities. This post was originally published on Sacred Matters.