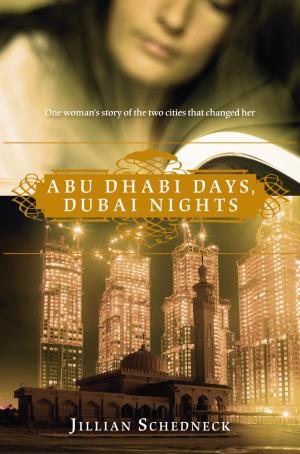

Abu Dhabi Days, Dubai Nights is an interesting and highly readable account of an American expatriate’s experience of living in the two city-states and has merit as an informative read about life in the United Arab Emirates.

The first half of the book is devoted to author Jillian Schedneck’s time teaching English at Abu Dhabi University. Fascinated by the U.A.E, she relates what drew her to the country, her initial impressions of life there—including her first Ramadan, gender segregation and issues regarding the conduct of male and female youth. The second half of her book unfolds after her move to Dubai, where she becomes a professor at the American University of Dubai. The environment there is much more liberal, as expatriates are in the majority. Both the Abu Dhabi and Dubai narratives are intertwined with the author’s romantic life and how it affected her experience in those places. The end of the book takes on a somber tone, however, when the author relates her experience at the women’s shelter, City of Hope (now officially called United Hope), and the media-fueled controversy surrounding the place.

I found the book to be quite engaging and thought the author did an effective job of interweaving a number of interesting and diverse narratives, such as the legacy of Sheikh Zayed, the conflicts between local dignity and foreign influence, and the author’s own love story. Having lived in the Gulf region for many years, I think Schedneck’s description is fitting when she points out that the growth and luxury of such cities seem to hollow—lacking a strong element of native subcultures or countercultures. I particularly appreciate the story of United Hope and the challenges expatriate women face when they are caught in abusive marriages or are abused by employers—these abuses, she explains, are compounded by unfavorable laws. She also notes the issue from the Emiratis’ perspective. Schedneck aptly quotes Sharlah Musabih, the founder of the United Hope, “To expect a country that is home to over two hundred nationalities to cope with both this rapid development and each other is just too much.”

Despite finding the stories intriguing, I am disappointed by some structural aspects of the book. There is no serious exploration of Emirati women and feminism, since the book’s synopsis hinted at introducing these issues. There are accounts of the author discussing Woolf and Chopin with both male and female university students, but they come across as a bit superficial. The reader is left without knowing if or how the students were changed by this discourse. Also, there is revolving door of Emirati characters, leaving the reader unable to get to know any one of them substantially. It was a strange to find her boyfriend as the most omnipresent secondary character when I expected in-depth characterizations of Emirati women.

There were also times when Schedneck’s well-intentioned exploration carelessly skims over religious and cultural mores. For example, in regards to veiling, she writes at one point that the “holy book does not stipulate female dress,” and that the verses that do mention it are only in reference to the Prophet’s wives. Later on, she adds that “the only mention of women’s clothing in the Koran is that women should dress modestly.” Taking such arbitrary liberties with Qur’anic interpretation in regards to female dress did not sit well with me at all, especially because she neglects to clarify her statements as being her opinion and that there are substantial differences of opinion and interpretation related applicability of those verses.

It is worth noting that throughout most of this book, Schedneck lives in a very insulated world of expatriates. Most of the time her “exploration” of Dubai is through high-end restaurants, nightclubs, hotels, and malls. She does try to break out of her bubble on some occasions, the most notable of them being her experience with the United Hope, the women’s shelter. However, she neglects to mention the human rights abuses inflicted on the male laborers who toil to construct the glittering city she inhabits. She only mentions them to draw attention to their “lonely, lusty, hateful stares.” I feel that it was a glaring omission to not, at least, mention their condition and how the treatment of these workers represents a much darker side of the Emirates.

I would still recommend the book to those who are interested in travel memoirs, simply because it draws attention to a region that does not often get written about in such a personal way. Although its scope is quite broad and the author’s privilege as an American expat is quite evident, it offers an intriguing firsthand perspective of the conditions and attitudes of expatriates, as well as Emiratis, within the context of the nation’s sudden economic growth.

Sarah Farrukh completed her B.Sc. in Social Sciences at the Lahore University of Management Sciences and is currently a Masters of Information student at the University of Toronto. She writes about faith and books at A Muslimah Writes.