Since the capture of Anders Behring Breivik, the Oslo terrorist and murderer, at least two critical issues have emerged. The first is his sanity, or lack thereof. The second is that Breivik’s assaults may have been ideologically motivated. According to Breivik’s logic, the murder of 76 people was necessary to challenge the Muslim takeover of the West. It was also an act directed at some of the people who, in his mind, were making the conquest possible: liberals or, more specifically, the Labor Party.

But as important as these issues may be for determining his status as a terrorist, there is another important point to consider about the ruthlessness of his intents and actions. Breivik, like the vast majority of terrorists in the world, was a male.

On the surface of things, this may be a rather obvious and seemingly trite point to make given the horrific nature of his actions. For most analysts, what matters is that he’s a fundamentalist Christian, a terrorist, a racist, a murderer and possibly insane.

But in his own mind, Breivik is also a patriot. He is a man committed to the defense of his nation from the external threat of the “Other” — in this case, the Muslim other. According to Breivik, Norway, and the West more generally, are locked in a struggle with two possible outcomes: a West dominated by Islam or free of its presence.

Sound familiar? It is. Much like bin Laden and his associates, the ideas and visions circulating in Breivik’s mind closely resemble the cosmic battle imagined in the minds of al Qaeda fighters: the fear, the external threat, the internal traitors, the violent resistance, the utopian future. Breivik, like bin Laden, is nothing short of the archetypal extremist whose ghastly deeds reveal the malevolence of passion when mixed with fear and hate.

But Breivik, like bin Laden and a long list of others, is a man. And like the many men before him guilty of pitiless crimes against humanity, he acted in a way that begs us to consider the relationship between such violence and his notions of manhood.

Why, in other words, do some men seem to find violence as a reasonable course of action when dealing with a perceived threat?

Part of the answer, we believe, has to do with something much larger than Breivik’s sound or unsound mind — gender. Men like Breivik all imagine their communities as uniquely feminine. This idea is effectively communicated through the language of their struggle. Breivik, for example, claimed to be defending the “honor” of the West and, in his manifesto, regularly refers to the “penetration” of Muslim armies throughout history and the “rape” of Europe.

These men also believe that, in defending some imagined “sacred community,” they are also defending manhood. Most of us think of communities as something like the family. We think of the people at the local and national levels as our brothers and sisters of sorts — people with whom we share duties and obligations. Beyond our borders, however, are the outsiders — the other families. In this sense Breivik is much like the rest of us: a modern-day tribalist.

Where Breivik and others stop being like us is how they think about the tribe. Breivik believes the west exists as an essentially pure and vulnerable tribe. An important aspect of Breivik’s actions lies in the fact that he believes the pure feminine family of the West needs protection by the warrior men of which he is a part.

A quick glance at Breivik’s 1,500 page manifesto reveals explicit antipathy for “feminism” and its role in the Islamization of Europe. He refers to the “Knights,” who will lead the revolution fighting “bravely” as men defending their civilization. The manifesto is all about a macho world waging war on “feminism” and “Muslims” at one and the same time.

Of course, this is not to say that women have refrained from the glory of human cruelty. But there is something peculiar about the fact that it is mostly men who commit the extreme violence of terrorism. For reasons rarely considered by analysts, men like Breivik seem to feel a great sense of urgency to act violently in the name of their people — imagined or real — and defend its honor and purity.

Thinking about Breivik and others like him, we might do well to think more about their manhood as much as their ideologies since, more often than not, the two seem to go hand-in-hand in the play of their madness.

Asma Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah. Michael Vicente Perez is Associate Editor of AltMuslimah. This article was originally posted on HuffPost Religion.

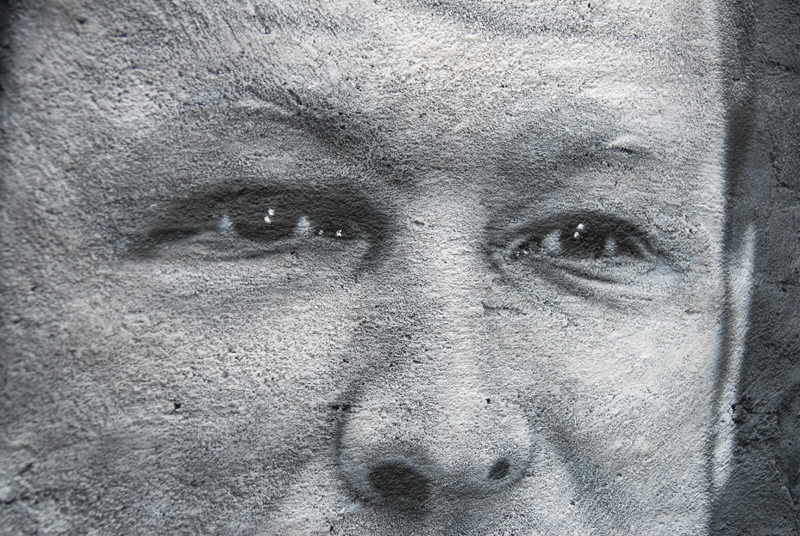

Photo: thierry ehrmann