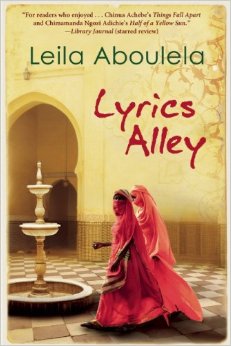

Lyrics Alley by Leila Aboulela is the evocative story of an affluent Sudanese family shaken by the shifting powers in their country and the near-tragedy that threatens the legacy they’ve built for decades. Moving from Sudanese alleys to cosmopolitan Cairo and a decimated postcolonial Britain, this sweeping tale of desire, loss, despair, and reconciliation is one of the most accomplished portraits ever written about Sudanese society at the time of independence. Here is a short excerpt.

Alhamdullilah, he was safe and the worst was over. Thank God, he was better today compared to yesterday – that was what everyone around her was saying, but Soraya was impatient. It was not enough that her beloved Uncle Mahmoud was recovering his appetite or talking to visitors about how the Korean War was likely to increase the price of cotton. Soraya wanted him as he was before, not weak and bedridden; she wanted him to be on his feet again, smiling and striding. Then they would slaughter sheep, or even a bull, to give thanks to his recovery, and beggars would crowd in through the gates of the saraya for their portion of cooked meat and bread. After that she would go back to school.

Soraya had been skipping school ever since the head of the family was taken ill; at a time like this she could not stay away. This evening, too, visitors were flowing in and out. Many of them had been before, and many would stay for supper. Today, Fatma and Nassir had come especially from Medani. It was Nassir’s duty to be by his father’s bedside; indeed, it was embarrassing that he had not come earlier. Soraya was delighted to see her older sister. They now sat on the steps of the garden, away from everyone else. Soon they would have to go and help prepare the supper trays for the men, but for now they could dawdle. The garden in front of them was shadowy and lush, and the warm air carried the repetitive croaking of frogs and the scents of jasmine and dust. Soraya glanced up and imagined that in the blur of stars and clouds there was the star she was named after; pretty, brilliant and poetic.

She turned to look at her sister, to gauge her mood. She wanted Fatma to be easy and generous when Nur came along. He would seek Soraya out as he always did, and tonight she wanted Fatma to be lax as a chaperone, neither serious nor grown-up. Soraya could remember when Fatma was unmarried and the two of them went to Sisters’ School every day with the driver, crossing the Umdurman Bridge, passing by the Palace, then turning right at the church. She remembered Fatma in her senior uniform, neat and vivacious, spluttering with laughter, screeching with her friends, her thin hair tightly held down with pins of different colours. She also remembered Fatma crying when she had to leave school, and how Sister Josephine had visited them at home to try and stop the wedding.

Fatma said, ‘We shouldn’t be here; we should be back there with my aunt frying the fish.’ But she did not move to get up.

‘You’re a guest. No one will expect you to help.’

‘Since when have I become a guest? In 1950 alone I came three times and each time I stayed over a month.’ She had taken offence.

Soraya tried to sound apologetic. ‘Everyone knows you must be tired after your journey from Medani. You can help out tomorrow.’

They were silent for a while, then Fatma said, ‘Has anyone been talking about me? About me and Nassir?’

‘What about?’

‘About us taking so long to get here. We should have been here days ago.’

‘Well, why weren’t you? The day Uncle Mahmoud fainted and the doctor came and said it was a diabetic coma – that was last Tuesday!’ Her voice carried the edge of accusation and her older sister folded her arms defensively.

‘So I’m right, everyone has been talking about us.’

‘Well, they were wondering.’

‘You know what Nassir is like. He wakes up at noon and every thing is an effort for him. He dithered and dithered: tomorrow we will travel to Umdurman, tomorrow we will leave. He couldn’t decide. He had to do thisfirst, he had to do that. Should we bring the children or leave them behind . . .’She lowered her voice.‘We had no idea how long we would need to be here. We could be stuck here if Uncle Mahmoud gets worse, and then what? So he hesitated and the days passed.’ She sighed and then said more sharply,‘If I had left him and came alone, which I could have done, it would have looked even worse!’

Soraya regretted this turn in the conversation. She did not want Fatma to be sullen and grumpy when Nur came. So now she said, ‘At least you’re here now. Stay as long as you can even when Uncle Mahmoud gets better – don’t leave.’

Fatma smiled. It was a sad smile. Soraya felt lucky she was not marrying a lazy, useless man like Nassir. It was said that he was an alcoholic and that people cheated him, that they borrowed from him and never paid him back. It was sometimes hard to believe that he was the son of Uncle Mahmoud, and Nur’s older brother.

Fatma said, ‘At first I used to think that Nassir would change, but now I am just glad that we are away in Medani. If he were here, Uncle Mahmoud would be critical of him and make his life miserable. And Hajjah Waheeba has such a sharp tongue!’

‘Well, maybe this is what he deserves.’

‘But I don’t want that for him! Maybe it’s because he’s my cousin that I feel soft towards him, but no matter how many faults he has, I don’t want anyone to rebuke him, even his father and mother.’

It was as if Fatma had said something profound and strange, because they both went quiet. It occurred to Soraya that Fatma had fallen in love with her husband. The idea was startling and disgusting. She could remember Fatma weeping because she had to leave school. She had seen her sleepwalk, passive and cool, into this marriage, and now she had become so protective of Nassir.

Soraya stood up, straightened her tobe around her and strained to look at the direction of the gate to see if Nur was coming.

She said, ‘I am the same age as you were when you left school and got married.’

‘Don’t worry, Soraya. When Sister Josephine came that day, Father promised her he would let you finish school.’

Would a promise given by the Abuzeid family to a head mistress be binding? But still, though she was a woman she was European, an Italian nun.

Soraya said, with a mischievous smile, ‘But I did get a proposal of marriage.’

Fatma shrieked, ‘And no one told me! I cannot believe it. It is as if Medani is at the end of the world, the way you people have forgotten me!’

This lively Fatma was the Fatma of long ago, the real young Fatma. Soraya laughed and put her arms around her sister.

‘How can we forget you? How can I forget you? Don’t you know how much I miss you?’

‘You never visit me.’ The reproach in her voice was sweet, without anger. She wanted reassurance, reassurance that mar riage and distance had not changed anything between them.

Soraya understood this and her voice was loving, ‘Because it’s better for you to come here. You enjoy yourself, and there are more of us here.’

Every time Fatma was due to give birth, she came from Medani and stayed with their elder sister, Halima. In her first pregnancy, when her morning sickness was severe, she had stayed in Umdurman from her second month until forty days after giving birth.

‘Anyway, anyway,’ Fatma was impatient, ‘tell me about this prospective bridegroom. He can’t be from the family.’

Soraya smiled. ‘You’re right. His father is a friend of Uncle Mahmoud. His mother came and spoke to Halima. She said that her son is going away to study in London and then he wants to be an ambassador. When we get independence, he will be one of the first ambassadors of Sudan abroad. As if I want to travel!’

‘You do, Soraya, you do.’

She did. Geography was a favourite subject. She gazed at maps and dreamt of the freshness and adventure of new cities. She loved travelling to Egypt, and how she didn’t have to wear a tobe in Cairo. She wore modern dresses and skirts and so did Fatma, and they went shopping in the evenings for sandals.

‘You would make a good ambassador’s wife,’ Fatma said slowly, looking into a future, a possibility.

‘Well, I have other commitments,’ Soraya whispered as coquettishly as she could, making herself sound like an actress in a film.

Fatma laughed. ‘What did Halima say to the mother of our future ambassador? How did she reject the proposal without offending her?’

‘Guess!’

‘She told her: “Soraya has already been spoken for by her cousin Nur”.’

Fatma said the most beautiful words in a normal voice, without a smile. All the joy was her younger sister’s and the anticipation that, within a few minutes, he would be here, sitting by her side under the stars.

Leila Aboulela started writing in 1992, and her first stories were broadcast on BBC Radio and an anthology Coloured Lights was published by Polygon in 2001. The Translator was first published to critical acclaim in 1999. It was long-listed for the Orange Prize 2000 and also long-listed for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Awards 2001. Leila Aboulela won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2000 for ‘The Museum’, published in Heinemann’s short-story collection, Opening Spaces.