Laila stared at a slab of pork at the supermarket and calculated the cost of a nervous breakdown: $150 an hour for the shrink, $200 a month for pills not covered by insurance, another $200 for a homeopathic doctor and nutritionist, at least $500 for a lawyer to write up her will in case she became suicidal, and $850 for a self-actualization yoga retreat in California. Throw in another $600 for a couple of colonics and a massage. Expensive. The one thing Laila had inherited from Fatima, besides the nose, was the ability to do math and shop at the same time. A nervous breakdown, along with all her other medical expenses, was just not in the family budget.

She would just have to settle for prayer, her husband’s response to everything these days. Or she just might get as much satisfaction out of purchasing pork.

It was so cold in the meat aisle that Laila found herself readjusting her wig as if it were a ski cap. She shivered and reached for the pinkish gray pork. Her hand jerked back. How did people touch this stuff? She watched a frazzled woman with three kids grab a large armful of packages – it was a pretty good pork sale. One of the kid’s suckers popped out of his mouth and landed where Laila used to have 36D breasts.

“Oh, I’m sorry, ma’am,” the woman apologized, reaching to pull off the Jolly Rancher.

Laila brushed the woman’s hand away. “It’s okay. My boys were always doing things like that,” she said and plucked the sucker off her sweater and handed it to the mother, who handed it back to the kid. This woman isn’t the germaphobe I was with my boys, Laila thought. The woman’s two other kids were now tossing one of the pork packages to each other as if it were a football.

“What do you do with this stuff?” Laila asked, pointing at the flying meat.

“The pork chops?”

“Yes, the pork.”

“Well, you can broil them and then cover them in barbecue sauce,” the woman recommended. “That’s what they do in the south.”

She pointed to a row of barbecue sauce bottles lined up above the pork section. Laila thanked her as she and her kids rolled away with their cart, which overflowed with cereal boxes redeemable via the coupons the youngest kid was waving around. Laila grabbed a bottle of barbecue sauce and then saw the price. $4.99 a bottle. It was a darn good thing she’d never eaten pork. She could get two bottles of ketchup for that price and that would take care of at least 50 hamburgers. She bought a couple of cans of tomato sauce instead. It was not like Ghazi had ever eaten pork. He wouldn’t know how it was supposed to be served.

As she put her groceries in the car, Laila almost slipped on a greasy rain puddle made last night during the first thunderstorm of summer. Typical Detroit. She could smell more rain on the way. She and Ghazi used to talk about moving to Florida when the kids grew up. In truth, she had only flown on an airplane once in her life, she’d never lived anywhere but Detroit, all her doctors were here, and her relationship with Ghazi wasn’t such that either relaxed at the thought of living in a place where the only people they would know were each other. And Ghazi’s mosque was here. She slammed the trunk hard.

When Laila had discovered her cancer, Ghazi had discovered Islam. Up until then they had been the kind of Muslims who fulfilled their duties by giving to the poor and not eating pork. They only knew when the Muslim holidays were when Ghazi’s mother called from Cairo to say Eid Mubarak. Now Ghazi was the kind of Muslim who went to the mosque five times a day, didn’t drink, and gave all the money he used to spend on his fancy gym membership to the new mosque, as if trading in fat for prayer would make his family healthy again.

Laila drove by the new mosque every time she went to Dearborn for cooking supplies – or real food, as Fatima called it. It was where she was heading now. She couldn’t just serve tomato sauce pork for dinner. She couldn’t miss the mosque’s minarets from the freeway. After all, Michigan’s Muslims bragged that the mosque was the largest one in North America.

At Greenland Supermarket, she bought halloumi cheese, a bag of pumpkin seeds, and a five liter bottle of olive oil from Lebanon, which she noted didn’t cost half as much as the pork, despite the sale. She usually got the ingredients to make foul for Ghazi, but today, for the first time in her marriage, she wasn’t in the mood. Amani, Ghazi’s mother, could make it for him later in the week. After all, she had come here from Cairo to help, as Ghazi described the purpose of her chaotic arrival.

The store was packed, as usual, and Laila waited in a very long line with women in headscarves, black abayas, or tight rayon tops with glitter designs. It all fit in here, but Laila remembered that when she was a girl it was very rare to see a headscarf, let alone an abaya, in Dearborn. The Arabs of her childhood had been blenders; they just mixed into the rest of the country. She didn’t even know where those Arabs were now, all those popular girls from high school.

The shoppers at Greenland, mostly women, checked each other out as usual, either in judgment or curiosity. Laila used to think that gave the hijabis the advantage because she couldn’t see the secrets under their scarves. However, now with the wig, she felt that they were on even ground, and she stared right back. It turned out that after all these years, she was a better starer than anyone else. A few minutes later, no one would look at her.

She turned her attention to the collage of posters at the exit behind the cashiers. Most featured big-eyed children in rags, lone figures amongst rubble – one sign asking in both English and Arabic to sponsor a child in the refugee camps, which Laila did, another asking to give money to the schools in southern Lebanon, which Laila did, another asking for contributions to restore Egypt’s classic black and white films, which Laila also did.

There were posters asking for money to rebuild Iraq. This Laila did not give to. Many of her neighbors had kids in the military, and Laila felt sad for them every day, but she did not agree with the destruction of Iraq and so she could not bring herself to give to its reconstruction. It was also how she had responded to the loss of her breasts. Ghazi had said that reconstructive surgery would make her feel like a woman again. But she still felt like a woman, even if he couldn’t see that anymore. Laila had found her cancer 430 days ago, the same day the US invaded Iraq.

The bagger, Ahmad, asked her how she was doing. Everyone in Dearborn knew her “situation,” as they called the cancer in whispers, because of Ghazi’s generous contributions to the mosque. Ahmad was a sweet kid, 24, about the same age as Zaki, her youngest. Ahmad had been in the U.S. only 14 months, and he always said how lucky her boys were to have her so close. He missed his mom. Laila would have definitely had a nervous breakdown if her sons had talked about missing her. But on the days when the boys took her to radiation instead of Ghazi, she smelled their fear through their clothes, which she still ironed for them. If her boys were married, they would not miss her so much if the cancer came back. When she had told them that if she died, they would want someone to lean on, they had told her that the cancer would not come back. They did not mention any girlfriends.

“I hope you can get your mom a visa soon, Ahmad,” Laila said, as she always did. “She won’t believe how successful you’ve become in such a short time.”

“Allah wa Akbar,” Ahmad grunted as he heaved the five liters of olive oil into the trunk. The pork bag tipped over.

“That’s funny looking chicken, Auntie,” he said.

Laila stepped in between him and the pork. “It was on sale,” she explained. “Fifty cents a pound. What can you expect for that, you know.”

Ahmad was impressed. Dearborn’s stores, like ethnic markets everywhere, sold meat and produce at rock bottom prices. But fifty cents a pound.

“You shop well, Auntie,” he said.

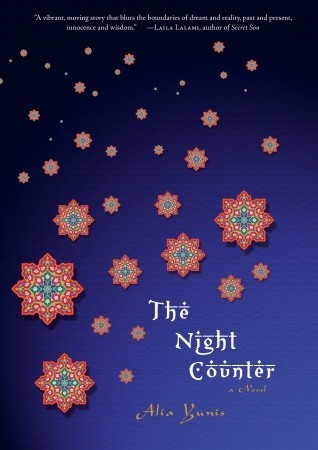

Alia Yunis, author of The Night Counter, was born in Chicago and grew up in the U.S., Greece, and the Middle East, particularly Beirut during its civil war. She has worked as a filmmaker and journalist in several cities, especially Los Angeles. Her fiction has appeared in several anthologies, including The Robert Olen Butler Best Short Stories collection, and her non-fiction work includes articles for The Los Angeles Times, Saveur, SportsTravel Magazine, and Aramco World. She currently teaches film and television at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi.