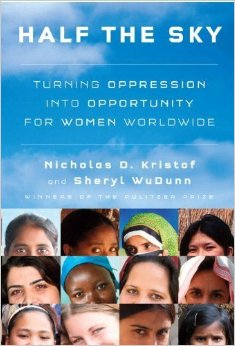

Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times, and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, have recently published an extraordinary book entitled Half The Sky: Turning Oppression Into Opportunity For Women Worldwide. The book is a call to action, primarily to Westerners, to become, at the very least, armchair philanthropists aware of the global plight of women. With a blend of research, personal relationships, and relevant narratives, the couple proves they have a deep understanding of the injustices occurring around the world, and an even deeper desire to educate others on the issues they are so passionate about.

The book feels at times like a journal of their travels, filled with anecdotes from those they’ve met along the way. Though every so often the solutions they offer may come across as patronizing or the stories they present as anomalies, I believe the book is a step in the right direction. WuDunn and Kristof openly discuss taboo topics, some which have not been presented in this magnitude before. Bringing issues to light is the first step in real change, and facing discomfort head on is precisely what they do. They posit a general framework of what is happening, what has been done, and most importantly, what needs to happen to drive change.

The authors argue that the overarching problems in regards to women are injustices that occur unnoticed. Many women go through life with little or no voice in their families and communities, are unprotected by the law, and are routinely disrespected. They offer education as the primary impetus for change. Throughout the book there are examples of how educating women and girls not only enhances their lives, but the lives of those around them. Though education is by no means a panacea, it is certainly helpful in bringing individuals and their families out of poverty. One such example given was Dai Manju, a young girl who lived in a shack with her family in central China. The family had no possessions, except for a pig and a coffin prepared for an elderly aunt. Her family never thought to send Dai to school, as it was expensive and seemed useless for a daughter who was destined to do household chores for life. However, Dai was the recipient of a scholarship which paid for her tuition from elementary school through college. She earned an accounting degree, and was able to move into the city after accepting a well paying job. She sent money home to her family, as did other girls from the town who had benefited from scholarships, and the town soon saw prosperity they had never known.

WuDunn and Kristof are not the first to recognize these problems affecting women, nor are they the first to write about them. In fact, there are countless publications outlining the injustices taking place globally. The difference between those studies and the book Half The Sky is simple: the stories. While reading their book, I was submerged in a world I hardly related to, and yet felt as though I could understand each and every woman they introduced. WuDunn and Kristof blend together stories from around the world, of women and girls dealing with the unimaginable, and overcoming seemingly impossible obstacles. As the authors explain, people react more to individual stories rather than statistics and numbers, and this point is demonstrated throughout the entire book.

It is becoming more and more known that the injustices in the world today disproportionately fall on women. But at the same time, women are increasingly more resilient. Many parts of Half The Sky are difficult to read: accounts of girls being promised work, and then sold into sex slavery, sometimes by family members; young girls being raped and contracting HIV; women subjected to rape as a weapon of war, only to become pregnant and having to give birth alone; women who die from diseases that are easily preventable; mothers who cannot afford to have fistulas repaired and go through life dealing with the embarrassing side effects. And yet despite the painful details each story is laced with hope. You can’t help but cheer for all the extraordinary women and rejoice in their victories. Take Mukhtar Mai, who was gang raped as punishment for the disgrace upon her family following the rape of her younger brother. She was sent home naked, ashamed, and bleeding; the village presumed she would commit suicide to fully cleanse the family’s dishonor. Instead, she fought against the injustice and was awarded monetary compensation, which she used to invest in local schools.

It is easy to feel overwhelmed by the magnitude of the issues presented by WuDunn and Kristof. But it is not their mission to make the reader feel guilty or defeated, but rather to bring a world that seems so far away into the reader’s life. As an educated white female living in the United States, I was constantly reminded of all the advantages and blessings bestowed upon me throughout my life. So how did they write a book that could be accessible by even those so far removed from the subject matter? They put faces to the problems and gave the atrocities personal stories. They showed the human side to what is usually described merely in numbers. It is hard to process the dire statistics that are often thrown our way, but when we are given a name and a face, we cannot help but feel something deeper.

This book is simply too important to not read or share. Kristof and WuDunn challenge the reader to do something with their newfound knowledge. They offer many simple things you can do from home: financing a micro loan through Kiva, signing up for email updates from sites such as World Pulse, or even making bigger commitments like sponsoring a child through World Vision or tithing 10% of your income to charities you believe in (and that support women’s causes!). This may be the most important book you can read this year, since it has the ability to raise awareness of a global catastrophe, can give voice to the voiceless, and through its readers, can be a catalyst for dramatic change in women’s lives around the world.

Hilary Pearson received a BA in Anthropology from Eastern University and is now a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania in Cultural Studies. She is particularly interested in environmental ethics and issues regarding women in developing countries.

I’m glad that the idea of personal narrarative has been affirmed through stories that the author chose to share. Hope and resilience are good but like any good qualities we can’t sort of dictate them but rather inspire and mentor. Everyone processes difficult experiences in various ways.

“While reading their book, I was submerged in a world I hardly related to, and yet felt as though I could understand each and every woman they introduced.”

Most books introduce you to different worlds, for example in different countries, but somehow they resonate enough that people do continue to read.