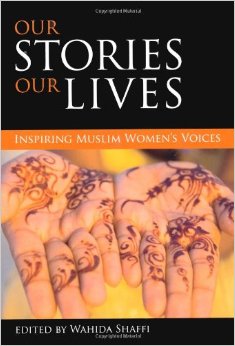

Our Stories, Our Lives is an anthology of a diverse group of women in Bradford, England, offering a glimpse into their lives and their struggle to reconcile their Muslim identities with their British ones. With the media’s daily onslaught against the image of Muslims, coupled with the assumptions about so-called conflicting alliances (Islam versus the West), a “proud British Muslim” would sound like an oxymoron to many. But it isn’t, and talking to many Muslims in Britain will tell you just that.

The book, edited by Wahida Shaffi, is based on an oral history project called Our Lives (also coordinated by Shaffi) and presents the stories of 20 women between the ages of 14 and 80, and their thoughts on being female and Muslim in Britain. Perhaps what peaks the reader’s interest even more is that all the stories are told against a geographical backdrop that has been historically colored by immigration and racial tensions. As the epicenter of the Rushdie affair in the 1980s, Bradford became a shorthand for the fragile relationship the country has with its Muslim population, an uneasiness that continues to this day.

Though as inspiring as most positive portrayals of Muslim women in the media, this book is not tantamount to the Muslim Women Power List that has been making its publicity rounds the last few months. Rather, these are women who resemble your mother, grandmother, daughter, and friends. Their stories are so deeply personal that you sometimes think you’re reading a private journal dripping with confessions and secrets. Far removed from the overarching debates about the hijab and burqa that seek to define Muslim womanhood are real women who struggle with their faith while balancing their careers and private life.

The most touching story in the book is Syima Merali’s dilemma of having to choose between serving alcohol in her restaurant or suffering the financial consequences. Although she worries that her earnings will be rendered haram, Merali decides to provide her customers with alcohol, all the while wearing her hijab. The compromise she makes echoes the many difficult concessions practicing Muslims make in a secular, predominantly non-Muslim country.

Another piece I found inspiring is Elana Davis’ “Music ‘n’ Motherhood,” in which she talks candidly about single-handedly raising her three sons the Islamic way and teaching street dancing at a local college. As a young convert who wears her Islamic identity proudly, Davis represents a face of Islam in Britain that now exists on the margins of history: Black Muslims have been in Britain since the 16th century and black conversion to Islam has been a growing phenomenon in the last two decades. Also a hijabi, does Davis find her street dancing and love for hip hop in contradiction with her religious identity? No, she says.

“Someone told me actually that I shouldn’t wear my scarf because I teach dance. I think if you listen to what everybody’s got to say, you will get confused, as at the end of the day, I became a Muslim for myself. I’ll learn myself, and if I do something wrong, that is something that I’m going to have to deal with, with God – nobody else”

There are several stories of unflinching patriotism from women who came to Britain to find a land of opportunity and the freedom to dress and express their religious and cultural identities however they please. Some found their British identity a refuge from the personal limitations placed by tradition and ancestral culture. While most British Muslims are expected to be two-dimensional characters defined by ethnicity and religion, women like Sensei Mumtaz Khan, a ju-jujitsu teacher, appear to trump their Islamic and Afghan identities. For Khan, ju-jitsu forms a core component of her life as she remains, conscientiously, a cultural Muslim.

Our Stories, Our Lives allows the voices of Muslim women to be heard rather than be silenced and spoken for (often through the mouthpiece of the media and community leaders, who are almost always men). The ever-expanding body of research and books on British Muslims shows that much more is needed to feed the political and public interest in an extremely visible but misunderstood religious minority. It also indicates that there is little informal communication bridging different ethnic and religious groups in Britain, and no swift end to the mystification of Muslim women in sight.

Alicia Izharuddin is a postgraduate student in Gender Studies at the School of Oriental African Studies in London with a keen interest in sexuality in Southeast Asia. She has written for a variety of media outlets on feminist and religious issues. An unedited version of this piece originallly appeared at Muslimah Media Watch,