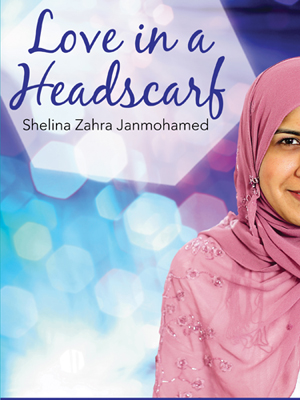

Like Divine Love, love for your spouse requires some extent of extinguishment of your “self”. Indeed, the very search for a husband teaches Shelina Zahra Janmohamed in her new book, Love in a Headscarf, her smallness in the larger landscape of the world. Love – with a lower-case “l” – happens when you just know that your partner is the person who completes you.

I recently finished reading Shelina Zahra Janmohamed’s, Love in a Headscarf: Muslim Woman Seeks the One. Simultaneous to my reading it, a passionate and compelling discussion on marriage in the Muslim community – for the most part Western Muslim community – was taking place right here on Altmuslimah. The perspectives of the book, and of the articles and commentary on the site, became interwoven, and my analysis of Shelina’s memoir was necessarily affected.

One Altmuslimah article on matrimony explored the increasing difficulties faced by educated, professional Muslim women in finding a suitable match. In When I Think About Marrying, Zeba Iqbal explored the sheer irony of being told throughout her life that success was defined in terms of a shining educational and professional career, only to later be regarded a failure because she hadn’t also been able to secure a husband.

Hussein Rashid responded to Zeba’s piece with his thoughts on Muslim men’s insecurities vis-à-vis highly successful Muslim women. He notes that women, to be considered successful, must achieve greater heights than men need to, resulting in a situation where “successful” men barely measure up to “successful” women, furthermore leading to men looking elsewhere for a wife.

In her book, Shelina offers similar insight. As she explains, Muslim women who grew up in the West have had to negotiate many different components of their identity – including their Muslimness (often reflected externally because of their headscarves) with their Westernness. These women’s notions of modesty and gender relations and career ambitions have all been analyzed both internally and externally, forcing them to redefine their femininity: “Femininity had changed and been updated by the challenges we had faced, and the outcome was stronger and more centred women.” (223)

In contrast, men haven’t been forced through struggles to update their notions of masculinity. And when faced with Muslim women who have, these men fail to rise to the challenge: “some of them now felt at worst threatened by the lively, energetic women who wanted a proactive spiritual and material life, or at best uninterested in them.” (223)

Shelina goes on to recommend “a collective reassessment of what it meant to be a man and what it meant to be a woman, a new gender reconstruction going back to the very roots of Islam, where men and women were partners and companions rather than disjointed and dysfunctional.” (223) Her experience had been that, growing up in the Muslim community, only girls were taught about marriage and relationships; it was time men, too, were educated on these matters, so as to “redress the asymmetry of marriage and the search for a partner.” (223)

Zeba, too, offered solutions in her article. She suggested that Muslim women be allowed to marry “nominally Muslim men”, defined as those who take the shahadah but who do not yet fully believe. The idea is that through time, and a nurturing marital relationship, the man’s heart will grow to accept and cherish Islam. Described in this way, it appears that Zeba is suggesting that marriage can be the beginning of a wonderful journey toward Divine Love.

Or perhaps I interpret her words this way because I read them while reading Shelina’s description of how her search for a husband necessarily, but somewhat inadvertently, paralleled her search for God’s Love. The search for a life partner requires considerable soul searching, and knowing oneself often reveals deeper insights about the universe and our Creator. The two go hand-in-hand. Of course, even upon marrying, self-awareness must be continually refined, and the journey to know God must go on.

This lifelong journey toward Divine Love is the crux of Shelina’s book, and a critical part of each individual’s search for their partner. It is while lying in the desert sands of Jordan one night, staring up at the canopy of stars, that Shelina realizes for the first time that romantic love is a stepping-stone to Divine Love:

“These two searches – for the love of a partner and for the love of the Sublime – these two loves ran intertwined. I didn’t have the words to explain this, but only later would I understand that these were the same search, the same love, which could not exist or be nurtured or thrive on their own. That is why romantic love seems so fulfilling to start with, because it reaches for another, deeper love. And that is why romantic love feels so empty as it runs its course unless it is replaced by a more profound long-lasting love.” (196)

Her metaphysical contemplations become deeper when she meets Mohamed – one in a series of men that she considers for marriage purposes. Mohamed, however, is different from the others in his penchant for philosophy and Sufi theology. He talks to Shelina about the middle path between extremes – how moderation is reflective of the siratul mustaqim, the ideal Straight Path that God always asks his followers to stay steadfast on.

More importantly, he tells her about certainty; about knowledge that goes beyond simply knowing, to tasting: “Imagine if you walked into the room and saw the fire yourself, then you would know for sure that a fire is there. But imagine you actually sat in the fire, then you would have certainty of what fire is. You would have tasted it and experienced it yourself.” (206-7)

Although things don’t work out with Mohamed, he plays a critical role in her path to the one – and the One. He develops her understanding of the intertwined searches, and teaches her that love for a partner is, like Divine Love, about certainty. Love, with a lower-case “l”, happens when you just know that your partner is the person who completes you.

Like Divine Love, love for your spouse requires some extent of extinguishment of your “self”. Indeed, the very search for a husband teaches Shelina her smallness in the larger landscape of the world. On page 248 she describes how the hajj made her realize that she is a speck in a sea of people. On page 249, she notes that the endurance of her search – with the many different men, with their many different quirks – gave her the insight to look deeper into people’s souls. Each person was a possibility, and she had learned through sheer endurance that success lay in exploring those possibilities.

Circling back to the marriage-related commentary on Altmuslimah – the articles and the reader responses – this element of Shelina’s search is key: whether it be Muslim men who are intimidated or turned off by successful women, or successful women who feel they cannot connect with anyone outside their intellectual sphere, perhaps the way forward is to put aside external categorizations and social expectations of “appropriate” matches, and to explore the possibilities that lie beyond.

(Photo: Alicepopkorn via flickr under a Creative Commons license)

Asma T. Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah