[title maintitle=”” subtitle=”An Excerpt From:”]

[title maintitle=”Betty Shabazz, Surviving Malcolm X” subtitle=”by Russell J. Rickford”]

Betty, you’ll have to speak for yourself.

— Juanita Poitier

Betty churned with rage, grief, and despair in her early widowhood. The beasts had slunk from their pit and robbed her of her hero, provider, and spiritual counselor. They had robbed her children of their father, her family of its patriarch. They had crushed hope, smeared truth, and destroyed her belief in humankind. “I lost faith in a lot of people,” she later said. “Not just white people—black people and people of all colors.”

Malcolm had warned that bitterness only debilitates. Wrath, he had counseled, would sap her creativity and devour her joy. But in the month after his death, she could find neither the weapons nor the will with which to fight. She expected her boiling insides to consume her. Or, she imagined, the toxic air itself would do her in. “She was in turmoil,” Dr. Ben later remembered.

Much of the brown and black world shared her anguish. In the days after the assassination, Muslims in Indonesia held prayer services in the minister’s honor, and a fiery demonstration flared in Guyana. Betty knew vaguely of the international ferment. Despite the slanted press coverage, there were comrades who advised her of the outcry. But she herself had never ventured outside the United States. Besides, Malcolm was dead, and all the hellraising in the Third World would not revive him.

Though pro-Malcolm rallies could not hearten her, the defamation deepened her wounds. “People forget what was being said about Malcolm at the time,” journalist Chuck Stone recalled. “They said death was too good for him.” The name that Harlem exalted was acid elsewhere. When Amiri Baraka later invoked Malcolm during a Newark speech before the alumni of Howard University, one of the nation’s leading black schools, the audience blanched. “Some of those Negroes actually booed,” he later remembered. Betty herself would proclaim her husband “the most slandered man in America.”

The enemy was everywhere, but the widow harbored special malice for the Nation, whose hierarchs she believed had helped arrange the minister’s death. “Sometimes she would curse when she talked about Elijah Muhammad and Farrakhan,” Ferguson later recalled. She abhorred the white power structure and its agents-the CIA, FBI, and the local police, who she was convinced had allowed if not orchestrated the hit. She also detested her husband’s blood brothers in the Nation of Islam, for their public betrayal, and many of his lieutenants, whom she suspected of treachery. One OAAU cofounder would remember that after the slaying, she treated even some of the most devoted disciples “like hustlers.”

Betty told an OAAU woman that the minister’s security detail should have ignored his orders not to frisk spectators on the day of the assassination. At times she seemed as bitter at the men who had failed to intercept the bullets as she was at those who had stood squeezing them into her husband. Both parties, she believed, were guilty. And both were black. In time, her mistrust and volatility antagonized even those Malcolmites who tried to stand by her. “The brothers didn’t know what to do, because they wanted to protect her,” Mitchell later said. While some of the disciples hoped to soothe her, others were “busy trying to act like they were her critics or advisers.”

The widow’s bitterness and suspicion only intensified when Malcolmites started leaving town. Fleeing fear, disillusionment, the threat of police persecution, and more bloodletting, many of Malcolm’s top deputies slipped away on the months after his death. Several landed in the Caribbean or Africa, where they set down for years. “All of them niggers done run out of town,” Sister Khadiyyah later remembered. “Like they got something to lose. Don’t nobody want them, but they was takin’ planes and trains.”

It was hardly idle paranoia that scattered them. Just three weeks after the assassination, a maid discovered the body of Leon Ameer, one of Malcolm’s top aides, sprawled in a Boston hotel room. Investigators ruled out foul play. Malcolm’s disciples were unconvinced. Even journalists with close ties to the minister had cause to fear. After he revealed in a Life magazine piece that Betty had shown him her late husband’s list of likely hit men, Gordon Parks learned from the FBI that four henchmen (presumably Black Muslims) had gotten orders to kill him. Within twenty-four hours, he and his entire family jetted off to a tropical seaside hideaway.

Fear clutched the widow, too, even cloistered in guest accommodations at Poitier’s remote manor. But she had never been the cowering sort, and she was too heartsick to dwell on the menace of the Nation’s zealots or the white establishment. Instead she sought composure. Donning Malcolm’s hat was some comfort. She had first slipped it on father intruders had firebombed their home. Now its powers multiplied. “It was my security blanket,” she later said. “When I wore it, I felt spiritually in touch with him.”

Betty was groping for serenity and a new role. Poitier soon discovered that her houseguest was totally unprepared for the public and private demands of her widowhood. Through her society contacts, Poitier managed to arrange a conversation between Betty and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s people. But as she later recalled, the talk did not go as she had planned:

I said, “Betty they want to talk to you. Tell them you want your children’s education taken care of.” And she said, “Oh no, I can’t do it.” I said, “You’ve got to ask them.” She said, “No, you ask.” And when they came over, she said, “Oh, I don’t want nothing,”

Poitier gently told Betty that she would have to swallow her pride. “At least you have somebody to protect you,” the widow cried. “Betty,” the hostess replied, “you’ll have to speak for yourself.” For seven years, Mrs. Malcolm X had left the speaking out to her husband, at least publicly. Now her pangs of loss were far more powerful than her grasp of his global meaning. “She was not ware of a lot of her African family,” Mrs. John Henrik Clarke would remember. Without a sophisticated sense of her husband’s legacy, the widow’s disillusionment with the struggle deepened. “She saw that Malcolm had given his life for black people,” Baraka later said. “And where was the reciprocation?”

Grief could have driven Betty mad.

“I could be someplace where somebody would be feeding me or changing my diapers, you know,” she later told an interviewer. She had no blueprint for survival without Malcolm. Squinting ahead, all she could see were the contours of more pain. If it were not for her daughters, she genuinely wondered if she would have bothered to pull herself upright every morning.

Her faith had been quitting her. Perhaps she felt its passing. Perhaps she was too numb to know the difference. Some of her brothers in Islam detected it, in any case. Only days after the minister’s funeral, Ahmed Osman and Said Ramadan, a young Harvard scholar, asked her to accompany them to Mecca in her husband’s stead.

“What I thought best was to take her out of the mood of the country,” Osman later remembered. The graduate student suspected that the Hajj would be an ideal remedy for the misery that had enveloped Betty.

She had been contemplating the pilgrimage for almost a year — since Malcolm had testified to its power in those ebullient letters. His death had dashed her tentative plans to make the journey. Now Poitier, who had marveled at how profoundly the experience had enriched the minister, urged her new friend to go. The widow agreed.

Again Osman hopped on the Greyhound, this time to meet Betty at the Saudi mission in Manhattan. The next few days vanished in a bleary rush about town. They secured a visa and certification of the widow’s authenticity from Muslim authorities in the city. Sheikh Faisal provided the requisite papers, recognizing her as a true convert to Islam based on her husband’s confession of the faith a year before. Saudi officials finalized arrangements with the World Muslim League, which agreed to sponsor the trip.

Osman’s fellow Sudanese immigrants saw him dashing about with Betty and thought he had lost his mind. “You crazy?” they said. “Maybe the CIA and FBI are following you.” Betty did not share Osman’s idealism. She worried about leaving the children for the month-long excursion. Then Antoinette Wallace agreed to help Poitier and another woman baby-sit Atallah, Qubilah, Ilyasah, and Gamilah while the widow was away.

In late March 1965, a month after she had watched assassins topple her husband, Betty kissed her daughters and, traveling under an assumed name, took off for the Holy Land. She hardly blinked during the flight. This was her first trip overseas, and she rippled with excitement as her escorts prepared her for the rituals of the pilgrimage. When the trio touched down in Beirut, Lebanon, where they were to spend the night, a local newspaper editor emerged to greet Betty and conduct an interview. (She refused to talk to correspondents for American news sources.) The Lebanese people knew of Malcolm from his travels through the Middle East and were quite in awe of his widow.

Betty and her companions arrived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the following day. She wore modest, flowing garments and a headpiece in the style of the other female pilgrims, all of whom left their faces unveiled. The men had wound two strips on unsewn white cloth about themselves like towels. Protocol officials met the widow and her escorts at the airport and whisked them to the Jeddah Palace Hotel, where they were to stay as guests of state. The Saudi government provided Betty with a chauffeured car and offered to cover all her expenses while she was in the country.

The following week was exhausting. Betty had entered the state of ihram, an abstemious phase that precedes the pilgrimage, but she had to balance the demanding Hajj preparations with newfound diplomatic duties. Saudi dignitaries were already queuing up to receive the widow of the Black American revolutionary who had first dazzled them the previous spring. Yet the dual role was a happy burden for Betty, who basked in the bureaucrats’ attention.

Here was the veneration for Malcolm that seemed so sparse back home. The Muslim world was especially reverent now that Malcolm had become a shaheed, a martyr in a righteous struggle (jihad) on behalf of Islam. Among the luminaries that greeted the widow was the secretary general of the World Muslim League, an elegant black Saudi named Saban. His grace so moved her that when her twins were born later that year, she bestowed upon each the middle name Saban in his honor.

There was not enough time to accommodate all the Saudi notables who wished the welcome Mrs. Malcolm X. As the pilgrimage season neared, her fellowship with the faithful ended and her communion with the creator began. She and her companions left Jeddah for the forty-five-mile drive into Mecca among busloads of pilgrims. There were blacks, whites, Asians, and Arabs. All wore the unadorned Hajj garb signifying the equality of humankind in Allah’s eyes. Along the route, the sojourners chanted the talbiyah:

Here we come, O Allah, here we come! Here we come. No partner have You. Here we come! Praise indeed, and blessings, are Yours — the Kingdom, too! No partner have you!

Malcolm himself had taught Betty the words. Now they awakened a prickling anticipation. Her excitement mounted as her car passed the white pillar marking the sacred territory and approached the outskirts of the holiest city in Islam. She traveled through the barren valley that encloses Mecca, marveling at the walls of craggy hills at its edges. Allah had certainly chosen a harsh landscape upon which to command Prophet Abraham (Ibrahim) to build His house. Finally the widow entered Mecca and beheld the Sacred Mosque.

It was majestic. Rearing from the bustling cityscape, the ornate worship place lofted seven minarets skyward. With the masses swarming its base, the edifice looked like the fusion of a coliseum and a temple. Following her guide, Betty made her way through the Gate of Peace into the droning multitude within the temple courtyard. At its center loomed the Kaaba, God’s house.

Betty for almost a year had joined more than three quarters of a billion believers worldwide in bowing for five daily prayers in the direction of the black cube, the symbolic center of Muslim worship. Now she was making her seven circumambulations about its faces, just as Malcolm had described in his letters. Like the minister, she chanted with the other pilgrims as she performed the revolutions, brimming with a sense of kinship. After making the prescribed circuits, she visited the Well of Zamzam. She had learned that Allah had revealed the oasis to the infant Ismael’s mother Hajar as she staggered through the desolate valley centuries ago. Now Betty renewed herself with the rich mineral water.

More than three months pregnant, she did her best to trot seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwah, mimicking Hajar’s frantic search for water in the wilderness. During the treks she prayed for mercy, as the forlorn mother once had. No other ritual would bring her more comfort. In the ensuing days, Betty proceeded east from Mecca to nearby Mina with the other women in her Hajj party. There she and her companions crowded into one of thousands of tents that blanketed the land like silken metropolis. The following morning was the day of standing. She rose with the others and advanced upon the Plain of Arafat. By noon the legions had flooded the barren expanse, more than one million believers come to renew their covenant with the Lord.

As she traveled internationally in later years, Betty would realize that Malcolm’s frothy accounts of Eastern Islam had wildly overstated the Muslim World’s colorblindness. White supremacy, she would discover, infected every head on the planet. Yet in the spring of 1965, as she ventured into the Arabian wasteland among the sea of pilgrims, she experienced the brotherhood that had so profoundly moved her husband. She saw the diversity of Islam, whose adherents hail not only from the Middle East, but Africa (almost 25 percent), the Indian subcontinent (30 percent), Southeast Asia (17 percent) as well as Latin America, Australia, the Caribbean, and Europe.

The widow worshipped under the wicked sun. She had not known what to expect during the wuquf, the pilgrim’s day of supplication on the Plain of Arafat. She understood that the rite was the centerpiece of the Hajj, and that no pilgrimage was complete without it. She knew that it was here, on the Mount of Mercy, that the Prophet Muhammad had delivered his farewell sermon in the seventh century. But would she experience fear, rage, or euphoria as she stood on the knuckled terrain? Was it possible that unpracticed in her faith and embittered with life, she would feel nothing at all?

The passing hours melted her anxiety. There was no lightning-bolt revelation or shuddering trance for the widow. But as she prayed in the boiling desert heat, whispering into the gloaming with the multitude, a warm tranquility enfolded her. Though Allah did not tell her how she would make it, she know He was listening. And when she finally turned to make her way back to the tent, she was sure He meant for her to survive.

This certainty buoyed her throughout the final days of the journey as she returned to Mina to rest and pelt Satan’s pillars before pressing onward to Mecca for the culminating Festival of Sacrifice. She had been reborn there in the Holy Land. Mecca’s camaraderie, climate, and symphony of cultures had enthralled and cleansed her. “The brotherhood that I have heard preached about all my life is here,” she wrote in a letter mailed to the Amsterdam News but addressed to the people of Harlem. “This ancient city with its beauty and sereness [sic] is indeed something for all men to behold.”

Betty did not share with Harlem the pilgrimage’s physical strain and humble accommodations. Pregnant and, by the standards of the region, pampered, Betty had struggled to complete many of the rituals. sleeping and sitting on rugs and performing arduous tasks in blistering heat with little refreshment. A year earlier, Malcolm had tried to hide his decidedly Western discomfort with some of the rigors of the Hajj. His widow was less subtle. “Why can’t we have a little comfort here?” she complained.

There were psychological hardships, too. Betty worried about her daughters. (Telephones were unavailable during much of the trip.) Between rituals she reminisced about her husband, remembering his bubbling accounts of the Hajj. But she had not grieved since she had arrived in the sacred territory. Even her despair was dissipating. Now back in Jeddah, she thought about the people everywhere who loved her because they loved Malcolm. She thought about those who had prayed for her and her girls. “I stopped focusing on the people who were trying to tear me and my family apart,” she later said. She reflected upon her children and her foster mother and the good souls she had left behind in the United States. Suddenly, she could not get back home quick enough.

But a final ceremony lay ahead. Though she had made no diplomatic requests, Betty learned that Prince Faisal. ruler of Saudi Arabia, would grant her and her escorts an audience at the palace. It was a fantastic honor — the prince was one of the most powerful men in the Arab World. Throughout the pilgrimage season, scores of visiting dignitaries would petition unsuccessfully to meet the busy monarch. Yet he had reserved time for the widow of the man he had received a year earlier as a Black America’s emissary.

Tall and well-formed, the prince strode forward to welcome Betty on an afternoon in late April. He offered his condolences, telling her that he appreciated Malcolm’s martyrdom. He uttered a few kind words about the minister. Then he opened his kingdom. “You and your children consider Saudi Arabia your country,” he declared. The prince was offering the widow and her daughters citizenship. He was inviting the family to settle permanently in Saudi Arabia as official guests. Osman hoped Betty would accept. To him, it seemed ideal opportunity for her and the children to escape the venomous climate of the United States. But New York was home, and anxious to get back, the widow declined the prince’s offer.

Days later, almost five weeks after they had arrived, she and her companions left the Holy Land. The journey had restored her emotional balance, replenished her sensibility and sense of worth, and deepened her commitment to orthodox Islam. Though she had recited the shahada, the confession to belief in one Lord — Allah — months before, in Mecca she had touched His cheek. “I knew, after the pilgrimage, that I was going to do it and that I could do it — with or without help,” she later said.

Somehow in the bustle of those weeks she had managed to send postcards to friends back home. One arrived for journalist Claude Lewis bearing the cursive signature of “Mrs. Malcolm X.” Upon the greeting card Alex Haley received was the autograph of “Mrs. Betty Malik Shabazz.” The widow sent Haley’s family her regards and announced that, “I am indeed happy to be making the Hajj.” In the card’s margin she scrawled yet another alias — an Arabic designation meaning “beautiful and radiant” that a female pilgrim had conferred upon her only days before.

“My new name,” Betty proclaimed, “is Bahiyah.”

[separator type=”thin”]

This was originally published on Ummah Wide, a digital media startup focused on stories and cultures that transcend the global borders and boundaries of the Muslim and Human family.

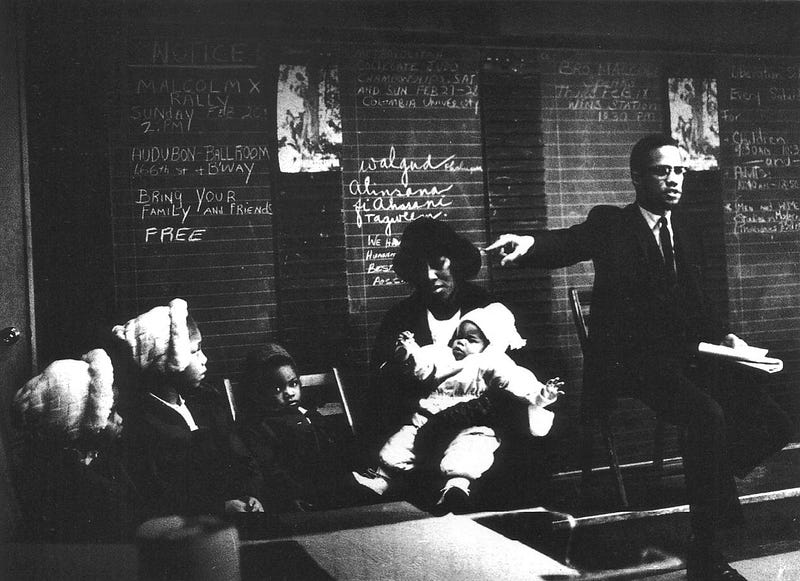

(Photo: Betty Shabazz at her husband Malcolm X’s funeral —Hartsdale, New York, March 4, 1965 — Photo Credit AP